“All this time, I’ve watched an unbroken river of foster youth come in after me,” Longworth said during one of two calls from prison with an Imprint reporter. “We weren’t born to be criminals, but compounded trauma led to this.”

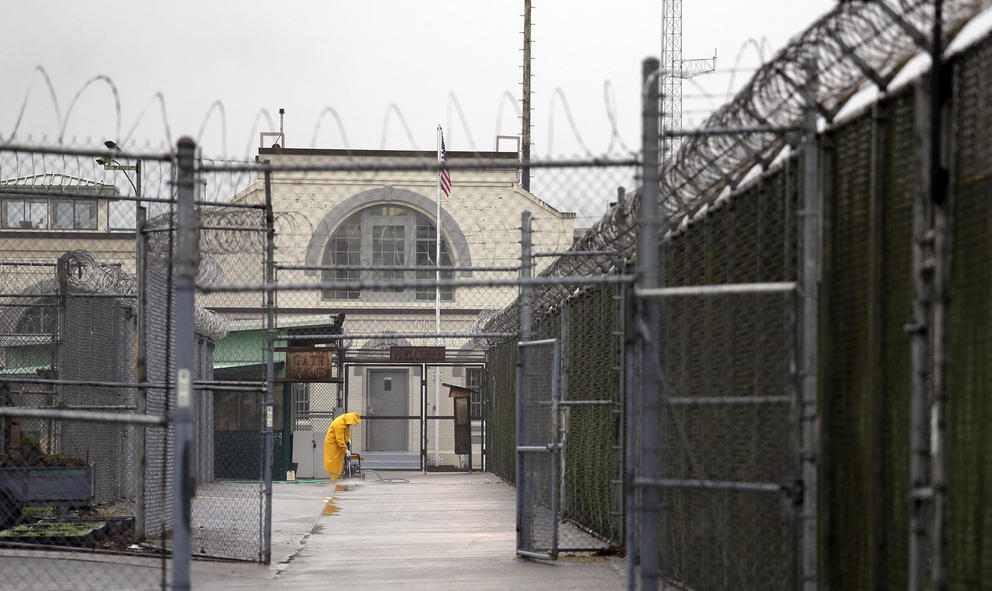

In May, Gov. Jay Inslee signed House Bill 1186, acknowledging the need to expand “trauma-informed, culturally relevant, racial equity-based, and developmentally appropriate therapeutic placement supports” in less restrictive community settings. The law that took effect July 25 will provide $11.2 million for a “community transition” program for young people now serving time in one of the state’s three juvenile detention centers — known as rehabilitation institutions — in Snoqualmie, Chehalis and Naselle.

A second law that takes effect this month, House Bill 1295, will increase educational opportunities for youth in juvenile detention, as well as those who’ve been released. The law requires state institutions to promote the same “on-time grade level progression and graduation” for youth in lockups as it does for students who are homeless or in foster care.

This story originally appeared in The Imprint on Aug. 9, 2021.

The new state laws apply to all those in juvenile detention settings — whose ages range, depending on the facility, from 11 to 25. Each year roughly 550 young people are released from juvenile rehabilitation facilities — 40% of whom have histories with the child welfare system, according to the nonprofit advocacy group Treehouse.

But all too often, they’ve been overlooked.

“The state loses track of foster youth,” Longworth said. Once locked up, “they are just incarcerated youth.”

Under the headline “Least Restrictive Options Lead to Better Lives,” Washington’s Department of Children, Youth and Families outlines research that supports its efforts to house juvenile offenders in community-based programs. It describes the settings as most likely to connect young adults to school and employment, while reducing recidivism and improving public safety. The harms of detention for children and youth are widely documented, resulting in poor mental and physical health outcomes, and a higher likelihood of future arrest and recidivism.

Under the new Washington law, young adults who have served at least 60% of their terms in state facilities run by the Department of Children, Youth and Families can be moved to less restrictive, community-based settings equipped with greater supportive services, including housing assistance, behavioral health treatment and help with independent living, employment and education. The expansive campuses, two of which are located in wooded settings, offer a range of services — from dialectical behavioral therapy to a forestry program and service dog training. Young people will be monitored electronically through tamper-proof ankle devices, in conjunction with the support services.

Testifying in February before the state Legislature in favor of greater investments for such alternatives to detention, Allison Krutsinger, a spokesperson for the Department of Children, Youth and Families, outlined the benefits for the youth and the public.

“Therapeutic, less restrictive and supportive options for youth and young adults transitioning back into their community will reduce recidivism and reduce the racial and ethnic disparities we see in our juvenile justice population,” Krutsinger said.

Longworth’s battle was not racism, but desperate poverty. In his memoir essay “How to Kill Someone,” which won first place in PEN America’s 2017 prison writing contest, Longworth wrote: “until the age of 11, I scraped out an existence in a lot of places, including for months in a rail yard in Portland, in a hobo camp on the banks of a river in Boise, and on the streets of Seattle.”

Caught by police for stealing to survive, Longworth was handed over to a state caseworker, and that’s when his foster care journey began.

The child welfare system placed him at two of Washington’s most notorious group homes, O.K. Boys Ranch and Kiwanis Vocational Home. Both closed in 1994, after allegations of physical and sexual abuse. In May, The Associated Press reported that the state has paid $29.6 million in claims made by 54 former Kiwanis residents as well as tens of millions paid to former Boys Ranch residents.

In his memoir, Longworth wrote that on his first night in the Kiwanis Vocational Home, the boy in the bunk below him was raped, as he listened “too frightened to breathe.”

Longworth recalled the boy crying out for help, “and the muffled screams I still hear.”

Running from more than a dozen foster care placements became a way of life. Longworth returned to the streets at age 16 with a seventh-grade education, no job skills and no government support, he said. His arrests began with charges of theft.

But in 1985, when he was 20, he was arrested for murdering an acquaintance, 25-year-old Cynthia Nelson, while involved in a plan to rob her home. He received a mandatory sentence of life without parole.

Longworth spent the first 20 years of his term in Walla Walla State Penitentiary. He struggled to read and write and hoped to obtain more education in prison, but found it difficult to access, turning instead to the prison library to teach himself, and learning to speak both Spanish and Mandarin, he wrote on his website.

After Longworth was moved to Monroe — a prison he described as having a calmer atmosphere than the one in Walla Walla — he helped found Concerned Lifers Organization, a group of men who seek to “better themselves and the community both inside and outside the walls.” They formed a youth advocacy group, and then the group known as State-Raised. Longworth said the group has about 100 members, a half dozen or so who meet weekly.

Treehouse began working with Longworth and the prison groups he belonged to in 2017. Just months before the pandemic forced the prison to bar visitors, the organization met in Monroe with policymakers and officials from schools and the child welfare and justice systems.

In 2019, Longworth had the opportunity to speak directly to Ross Hunter, Washington’s secretary of the Department of Children, Youth and Families, about the needs of foster youth who end up incarcerated, and he felt heard.

State statistics show that in Washington, nearly one in four young adults will be arrested within one year of aging out of foster care. There are similarly dismal outcomes for youth leaving detention centers. A recent state analysis that used 2015 data shows a 51% recidivism rate from juvenile rehabilitation facilities, with youth of color twice as likely to receive a new felony conviction than their white peers.

Dawn Rains, chief policy and strategy officer at Treehouse, said she had mixed feelings about the new state laws to address these long-standing problems. While they represent “a step in the right direction,” she’s concerned that foster youth who are incarcerated and need special educational services — as many as 50% to 60% by her estimate — may still not have their needs met.

The new law supporting transitions to community-based settings, however, leaves her more hopeful: “The right kind of intervention and wraparound support can really change the trajectory of a life,” she said.

Rains and other youth advocates are also encouraged by the growing influence of young people in crafting statewide reforms.

Last spring, as the bill seeking to transition young adults into less restrictive, community-based settings worked its way through the Legislature, the Department of Children, Youth and Families arranged for several incarcerated youth from the Green Hill School to testify at the state Capitol, including Aaron Toleafoa. He asked legislators to support the bill because it would lay “a strong foundation for their future lives outside the system.”

Longworth pointed as well to hope emerging in the courts. In March, the Washington Supreme Court found mandatory life without parole sentences unconstitutional for offenders younger than 21. That means he and others like him — having served much of their lives behind bars — could soon have their cases reexamined.

“When I came in as a broken foster youth, I thought this is just me. I was born bad,” Longworth said. He explained that he takes responsibility for the crime he committed as a young person, but added, “we weren't born this way. It's the way we were raised.”