Madigan and her husband, Jason, had set up a formal dinner for Christian as nicely as they could, considering the conditions: an overcast day with rain, a cold metal picnic table partly covered by an overhead eave, and a propane tower heater that, for safety reasons, sat too far away to be of use. It would also double as their Christmas visit, as the facility limited the number of visitors per day.

The family was one of many trying to make birthdays and holidays special after Gov. Jay Inslee banned in-person visits to inpatient state facilities starting March 10 in order to help curb the spread of COVID-19. Starting in September, families were allowed up to four-hour outdoor visits. Parents and caregivers agreed that safety protocols are there to keep staff and youth safe, but as the colder weather started bringing snow flurries and rainfall, they complained of inappropriate shelter and no sources of heat.

The Madigans’ original plan was to purchase a space heater and extension cord to run outside for their Christmas and birthday visit. By the time it rolled around, a staff member had personally acquired the propane heater for visits, according to parents, but it regularly ran out of propane.

For the Madigans, the visit was only the second time seeing Christian in person since his admittance in July, a result of COVID-19 restrictions and the four-hour drive to the facility. But Richelle Madigan said she could tell Christian felt “like a million bucks” because of how he carried himself in his suit, “in a fancy, debonair kind of fashion, which was really cute,” she said.

The constant rain and cold quickly dampened their mood, however. Madigan said she left the visit in tears and her husband in anger. Her husband’s shoes were still wet three days later. They had planned on the maximum visitation of four hours, but they ended the visit after one hour because everyone was too miserable.

“[Christian] felt terrible when he had to look us in the eyes and say, ‘I really don’t want to leave you guys, but I’m so cold. I’m freezing. I need to go inside,’ ” Madigan said. “He was genuinely heartbroken to have to tell us that, and it made me think how cold is he? How long has he been waiting to tell us that?”

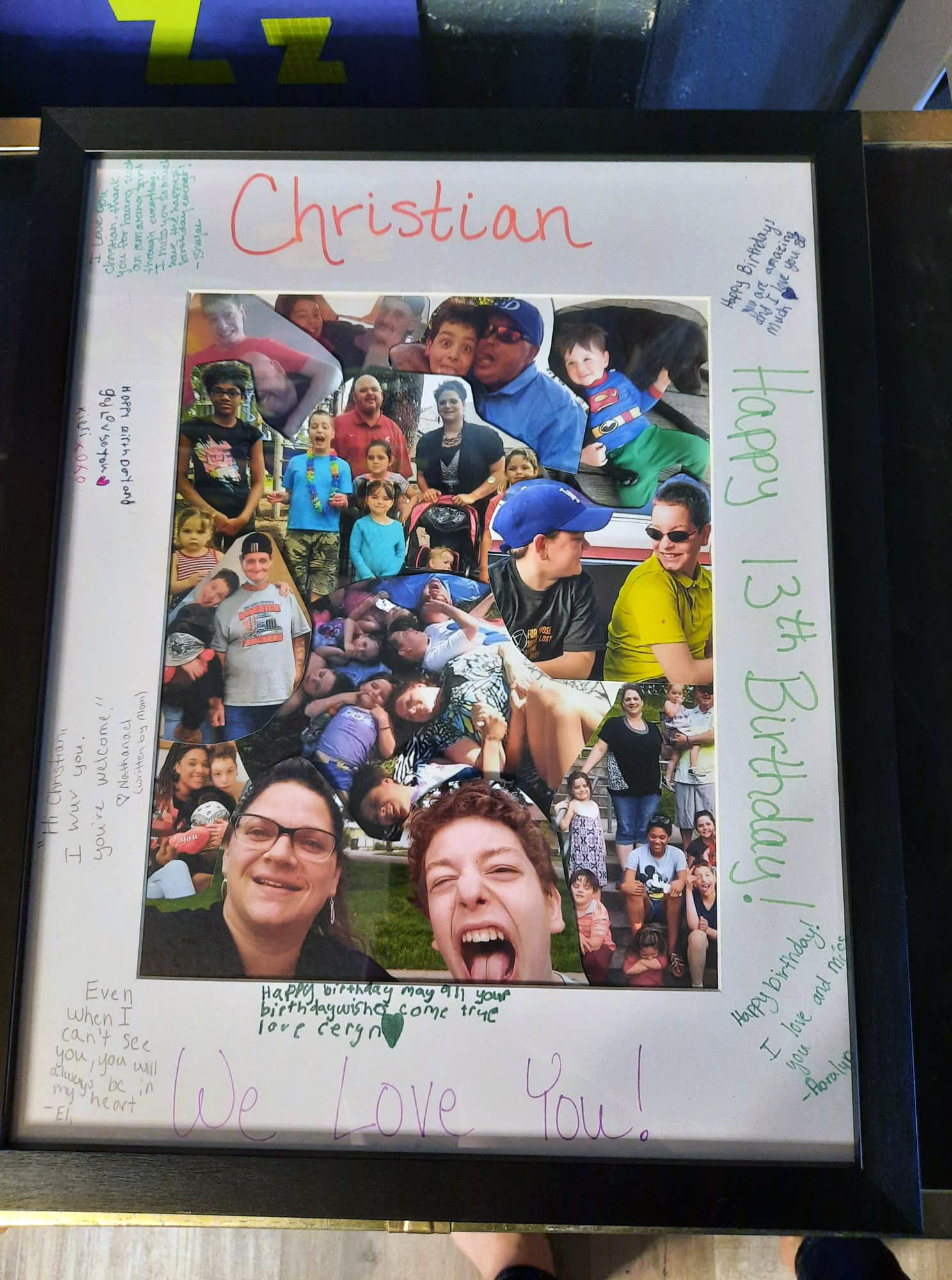

Madigan had spent weeks preparing for their visit. Special food and desserts, flatware and table settings, flameless candles, a tablecloth with a framed photo collage from his siblings, a personalized ring made from silicone for safety and a long letter from Richelle about how they believe in Christian’s future and are committed to his life.

While she ended up drenched and cold, Madigan said they were still grateful to have a moment together. “The look on his face was absolutely priceless,” she said.

But Madigan is especially frustrated because she works at a casino that has moved its entire operations outside, using a diesel generator that pumps heat through ducts. It keeps her so warm outside, she doesn’t need a coat, she said, and wonders why the state can’t come up with solutions for children in state facilities and their families.

“It's creating the appearance that we're saying, Oh, well, our restaurant [and] casino customers are more important to keep warm than our kids, that are the most vulnerable ones, which are inpatient treatment [youth],” Madigan said. “This is a fairly easy fix, and we’re not fixing it, but that for me is the frustration.”

Christian hasn’t lived at home for the past five years, spending time in emergency rooms or inpatient facilities to address his more severe behavioral needs. It’s likely he’ll end up at a specialized out-of-state behavioral health facility after Lakewood, Madigan said, so it’s “soul crushing” to have him this close by yet have such short visits. With seven other kids to wrangle and child care to procure, even an in-state visit is challenging, so they want every visit to count.

Christian lives in the moment, so when it gets cold, he thinks more about the short-term (getting warm) than the long term (not seeing his family), Madigan said. But when she asks Christian about visiting, he gets absolutely elated. They have regular phone calls and video chats in the meantime, but physical visits are especially important for emotionally dysregulated kids who need to practice social behaviors. Because touching is not encouraged on campus, hugs from parents are another vital aspect of an in-person visit.

Madigan stressed over and over how the facility staff and treatment teams have been wonderful, but she remains frustrated with the state departments that make the decisions about family visits.

“It’s hard on the kids, it’s hard on the families. I think it’s really hard on the CSTC staff, too, because they are the ones who have to pick up the pieces, both for the parents and the kids,” Madigan said. “With all of the things right now in COVID times that are outside of our control, this is something that could be an easy fix, that could alleviate a lot of stress for a lot of folks.”

One parent said Tony Bowie, CEO of the Child Study and Treatment Center, sent out a letter stating that visits would remain outside because of the rising number of COVID-19 cases, and a general acknowledgment of cold weather and promises of heat sources on the way.

Yet two months later, heat sources still weren’t provided by the facility. It took until the week of Christmas for the tower propane heater to arrive, and it was supplied personally by one of the staff. Bowie said the facility will purchase propane refills from now on, and it will no longer be the responsibility of the staff member.

Bowie said that the hold up in purchasing heating towers resulted from a general shortage, with restaurants sucking up most of the supply when many moved seating outside. However, more patio heaters are on the way, Bowie said, and should arrive within five to seven days.

He said outdoor visits are purely a result of the governor’s proclamation, and the facility must follow those state restrictions. It started with L-shaped tents with siding to protect from the elements, but winds blew all six tents over, leading to the use of tents with only overhead cover.

Bowie said the facility plans to build permanent structures. Two gazebos are waiting to be installed, and a third will be purchased or built soon. They’re waiting on cement pads to be built so the structures will have secure foundations. But Bowie said they’re waiting on a contractor and have no date of completion.

Julia Duin, an Issaquah freelance journalist whose 15-year-old daughter, Olivia, is at the facility, thinks that heating sources should have arrived by now, a full two months after the letter was sent to her, but definitely in time for holiday visits.

She currently drives an hour, in good traffic, to visit Olivia, who has been there since Jan. 8. She has autisticlike tendencies and a rare genetic disorder that prevented her brain from fully developing, resulting in violent behaviors.

When visitors arrive at the facility, they check in inside a building, are given medical grade masks and have their temperatures taken. They’re then ushered back outside for the actual visit. Duin often brings treats like bubble tea that Olivia can’t get inside the facility. Normally they would take off — go shopping, to church, to a restaurant — but since COVID-19 shut down off-campus visits, they huddle together in sweatshirts and blankets on metal picnic tables. The facility has since set up a large gazebo tent, but it has no sides, Duin said, and the temperature has dipped to shivering levels.

Duin said she’s asked for some kind of heater and never received a response.

On her latest visit, on Dec. 18, the propane tower heater had finally arrived. Duin said one of the staff got it from a relative, but the heater ran out of propane, so families after her couldn’t use it.

“She’s dying to see me. I mean, she’s basically racing toward the door, ” Duin said of the visits. “She loves it because I bring her food. I hug her — she gets hugged. They’re not really allowed to touch each other inside.”

But Olivia, like Christian, is sensitive to the cold and often wants to go inside long before the visit ends. While Duin had gifts prepared for their Christmas visit on the 23rd, her daughter had acted out and lost her visitation privileges for the day.

“It’s just sorrow upon sorrow,” Duin wrote in an email accompanied by a photo of Olivia, draped in a blanket, swaddled in a hoodie and jacket. Olivia hasn’t left the campus since mid-March, Duin said, except for two medical visits, so these in-person visits are both needed for Olivia’s mental health and her practicing social behaviors outside of the facility environment.

Her wrapped gifts, carefully selected because of the many limitations for inpatient residents, will be accompanied by hot cocoa once Duin can visit again. While she is grateful for the visits, Duin said frustration levels are at all-time highs. She said she’s often called state representatives while shivering under the tent to illustrate how current protocols dictate what her visits look like.

“I’m just beyond angry because I feel like these state officials, they’re not sitting outside for 52 or 42 degree weather, wrapped up in blankets trying to console their child,” Duin said. “What’s the use of allowed visits, if you make it so difficult for the parents to have them?”

Richelle Madigan stands outside in her yard near Moses Lake on May 28, 2020, with two of her daughters, Ceryn, 9, and Aaralyn, 5. She balances a photo of son Christian on top of one of the few possessions Christian came with from his last foster parent: a child's play car. Christian went through two foster homes before he came to the Madigans, but now, he's finally home: "We made a commitment to him that we would stay no matter what," Madigan said. (Emily McCarty/Crosscut)