The extension came the day after environmental justice advocacy groups Puget Sound Sage and the Sierra Club held a press conference on the steps of the Legislative Building in Olympia and delivered a larger-than-life disconnection notice to the Governor’s Mansion.

“What we’re hearing from our communities is that we are in crisis, and we need the government and leadership to step up to keep our communities safe and help us weather this storm,” says Katrina Peterson, climate justice program manager at Puget Sound Sage. “Right now, the pandemic is worse in Washington state than it was when we first had the moratorium put in place.”

The utility disconnection notice to the Governor’s Mansion was purely symbolic. But for Washingtonians living on the edge of a fraying social safety net, such a notice can signal looming disaster.

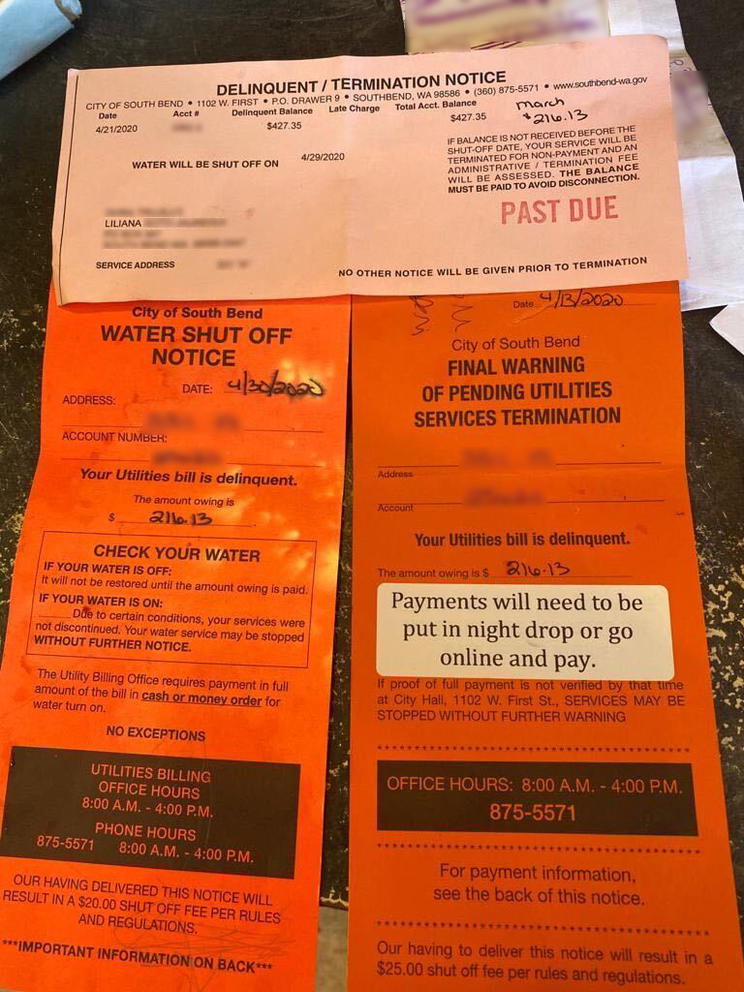

For Liliana, a mother of six who requested that her last name be withheld because of her undocumented immigration status, the bright orange notices that began appearing on her door in March exacerbated the pandemic’s many stressors.

During the first week of March, Liliana’s husband lost his seafood industry job in South Bend, a Pacific County town of 1,625 nestled along the last bend in the Willapa River before it empties into Willapa Bay. Liliana also worked in the seafood industry; a workplace injury she sustained in June 2019 finally forced her off the job in February. With the pandemic gaining traction across the United States, both parents suddenly found themselves without jobs, and it would be three months before Liliana’s husband was able to find another one.

But on April 30, the family received notice that their water would be shut off because they hadn’t paid their March bill. They owed $216.

“We didn’t have enough money to pay the bills or the rent,” Liliana said through a Spanish translator in a recent interview. “Our water got shut off in May — even though my husband went out to talk to the person who was going to shut off our water and let him know that we’re both not working, we have lots of kids at home and it’s a difficult moment. We need water to eat and to wash our hands.”

A friend connected Liliana with Firelands Workers United, a nonprofit focused on organizing working people in rural southwest Washington. Stina Janssen, the executive director of Firelands, called the city of South Bend and got the family’s water turned back on within 2½ hours.

“The moratoriums have been really essential to clarify that in a place where there’s plenty to go around, nobody should be cut off from water to wash their hands or power to cook a meal just because they don’t have enough money to pay their bill,” says Janssen.

Inslee’s original moratorium, signed March 18, strongly encouraged (but didn't require) utilities to stop disconnections for nonpayment, and many of the bigger utilities voluntarily agreed to quit cutting off people's power and water. But South Bend didn't. The city sent notices of impending disconnection to Liliana's family in March and sent another on April 13.

Inslee then signed a new version of the moratorium on April 17; it explicitly banned utilities from doing nonpayment disconnections. So the notices that South Bend sent Liliana before April 17 were technically legal, and without the expanded moratorium, the disconnection would have been, too.

“That was definitely an oversight on our part,” says Dee Roberts, clerk-treasurer of the city of South Bend. “We are still sending out delinquent notices so people are at least aware of what their bill is.” Roberts adds that the city hasn’t shut off anyone else’s water or issued shutoff notices since Liliana’s situation was resolved.

“I personally was getting phone calls and was supporting several people and families by calling the utility and the city. I did translation. In my experience, the utilities were very gracious, but they didn’t have a lot of clear information,” says Janssen.

Options for help are limited for undocumented immigrants like Liliana. Although all pay taxes, they do not qualify for unemployment assistance or the $1,200 stimulus checks that many American citizens received from the federal government in April. What little assistance is available can be difficult to access for those who don’t speak English.

Roberts estimates that the water and sewer bill for one household in South Bend averages about $200 a month. She says the cost is above average because the city is paying down its debt on a new regional water treatment plant. With money the city received from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, or CARES, which Congress passed in March, South Bend has begun offering grants of up to $300 to help its residents pay their bills.

But for now, the application for those grants is available only in English. Roberts says there is one bilingual police officer in town who sometimes helps her translate documents into Spanish, but he hasn’t translated that application yet.

Washington’s state-level energy bill assistance program, the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), can be used only once per year in normal times. LIHEAP allowed Washington residents to apply for aid a second time this year after the pandemic started, but Janssen is concerned that this won’t be enough to help families who have been without work for five or more months.

And even though disconnections have ended for now, utility bills still pile up, often alongside others, like rent.

“Getting a disconnect notice can be a really stressful thing, especially if you’ve lost your job, or if your unemployment benefits just ended,” says Lauren McCloy, senior policy adviser on energy to Inslee. “We think that it’s important to continue to support people during this time when they’re facing a lot of economic insecurity.”

But McCloy says the state recognizes that depending on how long the pandemic lasts, many people may ultimately face large stacks of unpaid bills, and that the governor’s office hopes that Congress will again act to help states and cities get more money to people in need.

“Folks should try to pay what they can,” McCloy says. “At the end of the day, the last thing we want is for people to be racking up these large debts that are then harder to pay later.”

In South Bend, Roberts says the city realizes that there will be people behind on bills for the foreseeable future; she says her small department will handle situations on a case-by-case basis. The city is considering trying to partner with a local nonprofit so that people in need can apply for more assistance.

A LIHEAP grant enabled Liliana to pay off her overdue light, water and waste removal bills, but she still worries daily that her husband could lose hours at his new job. She worries that she cannot provide for her children, and she says her oldest children, 15 and 16 years old, are stressed by watching their parents struggle.

“This month, I have to start paying those [bills] again and I’m already three months behind on rent,” Liliana says. “The way I look at it is that I have to keep looking forward, not give up and trust that God will help us.”