While the Department of Corrections contends it investigates every inmate death, those inquiries aren't regularly shared outside the department. State Sen. Jeannie Darneille, D-Tacoma, said she and other legislators receive little insight into why inmates die or what changes prison system administrators make to correct errors.

“It’s an afterthought for the department to engage legislators on deaths,” Darneille said in a recent interview. At present, she said, accountability “really has not happened in any substantial way.”

Addressing an oversight bill Darneille introduced, department medical leaders pointed to nascent initiatives to investigate health care failures that put inmates' lives at risk. The implication during a January hearing was that, in the department’s view, independent oversight would be overkill.

Death rates are rising in America’s prisons even as prison populations slowly shrink after a generation of explosive growth. Nearly all die of illness; medical issues accounted for 89% of the 677 prisoner deaths recorded in Washington from 2001 to 2019. The coronavirus is expected to cause a spike in deaths, as prisons everywhere in the U.S. struggle to contain the virus.

Even as the number of prisoners crept down, the national death toll rose 15% from 2006 to 2016, to 4,100, according to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report released in February. While many of the dead may be elderly lifers, about a third of prisoners who die inside are under 55.

A committee launched in mid-2019 to review problematic care at Washington state prisons was shut down months later after complaints from prison medical directors, a former leader in the department’s health services division told Crosscut. A department spokesperson said the program was reconstituted recently by a new quality control team.

Other internal processes failed to detect apparent negligence that led to the deaths of seven inmates at the Monroe Correctional Complex, the prison system’s health hub. Critics argue the the state Department of Corrections, which has been without a permanent head of medical services since early March, is unable to police itself.

‘A black box’

When a prisoner dies, the results of internal death investigations are rarely shared outside the department. Lawmakers and bereaved family members are often left guessing.

Attorney Ed Budge, who for two decades has represented inmates and their families, described prison as a “black box.” Prison administrators control the flow of information and can hamstring lawyers’ efforts to investigate inmates’ claims. Bereaved family members are shut out.

“The overarching concern for most clients is to learn what happened,” the Seattle attorney said. “People want answers. People want to know why their loved one died and whether something should have been done.”

Secrecy breeds “wives’ tales and urban legends” that find fertile ground among prisoners, Johnny Cachero said. With the pandemic flaring, Cachero, a former Corrections Department inmate released in 2011, said incarcerated people worry they’ll be left to die in their cells if the coronavirus incapacitates prison staff.

Cachero has little good to say about the years he spent inside. (The highlight was meeting political activist Angela Davis, who told Cachero and other inmates at Clallam Bay Corrections Center to embrace feminism.) A talkative Toastmaster with a flair for obscenity, Cachero described his former jailers as white “ex-blue collar, podunk town people that have say-so over all of the different races.”

“You've got a bunch of flies in a bottle, and they've got a big magnifying glass,” said Cachero, who received a nine-year sentence for an unarmed robbery. The holdup left him $1,682 richer for the minutes it took police to arrest him outside the downtown Seattle bank he had just robbed.

Inmates, to Cachero’s eye, are not treated as human beings. Medical care, he said, is almost impossible to get and rarely worth the $4 copay charged prisoners earning at most about $55 a month. The results are often horrifying.

In an interview, Cachero recalled an inmate dying of tuberculosis in his cell. Another man, a diabetic whose foot had grown necrotic, went into surgery only to have the wrong foot partially amputated; surgeons wound up redoing the surgery on the correct leg.

“He came in walking,” Cachero said. “And he left with half a foot and no leg.”

Cachero’s experience with medical treatment in custody was, he said, typical. He has an inflammatory skin condition, plaque psoriasis, which he describes as “human mange.” It’s intermittent and treatable with a high-strength steroid ointment.

Though he had been prescribed the cream for much of his life, medical staff refused to issue him a tube. He said he was left scratching at “open and festering” wounds for weeks before the nurses relented. Many other prisoners, he said, had it worse.

“If you're a stand-up, old-school, knock-around guy, you're not afraid of anything,” he said. But “to really be sick in prison, it's a scary thing. …

“For men like us, the biggest failure is to die in prison.”

A Department of Corrections medical bag lies on the floor inside a cell at Stafford Creek Corrections Center in Aberdeen, Jan. 13, 2014, after an incarcerated man confined there died by suicide. The man, who had a documented history of mental illness, had been released from suicide watch days before. (Washington Department of Corrections)

At their mercy

When prisoners get sick, they basically have to ask prison staff for help and, if it doesn’t come, keep asking and hope for the best.

“You have zero power to get your own health care. Zero power to see doctors. Zero power to get your own medications,” Budge said. “And if the people who are running the [facility] decide that they're not going to help you … you're pretty much at their mercy.”

Prison system administrators alone decide how to ration that mercy. Unlike hospitals, which must be accredited to bill Medicare or Medicaid, correctional health systems need not seek outside accreditation because they only bill themselves.

While the state Department of Health licenses prison medical workers, efforts to prompt Health Department investigations of in-prison practices haven’t amounted to much, said Rachael Seevers, an attorney with Disability Rights Washington advocating for people held in state institutions.

Frustrated by the Department of Corrections’ unwillingness to provide inmates with basic medical care or equipment like back braces, Seevers had been suggesting prisoners file complaints with the state Health Department. The complaints frustrated prison providers, Seevers said, but didn’t ultimately improve the situation.

Although about half the calls she receives from prisoners relate to medical care, Seevers said her office rarely pursues those claims.

“Honestly, we no longer take very many medical cases because it ends badly every time,” Seevers said. “It's been really hard to effect change.”

Complaints related to health care, Seevers said, are usually handed off to the Office of Corrections Ombuds, an oversight organization that went into operation in the governor's office two years ago.

The prison system faces about 4,100 official complaints related to health care from prisoners each year, hundreds of which lead to administrative claims and lawsuits. But Seevers and others said plenty of valid complaints go unheard.

Budge said he and his law partners take on about 1% of the clients who arrive at their door. Many of the other claims have merit but are too risky to justify the upfront costs.

To win in court, prisoners or their family must show prison officials were intentionally cruel, a standard that’s difficult to satisfy when prisons shield themselves from public inquiry, Budge said. Often there’s no investigation to draw on.

“There is no thorough review,” the Seattle attorney said. “There are no mortality review findings, and the system doesn't change.”

‘We can show you some results’

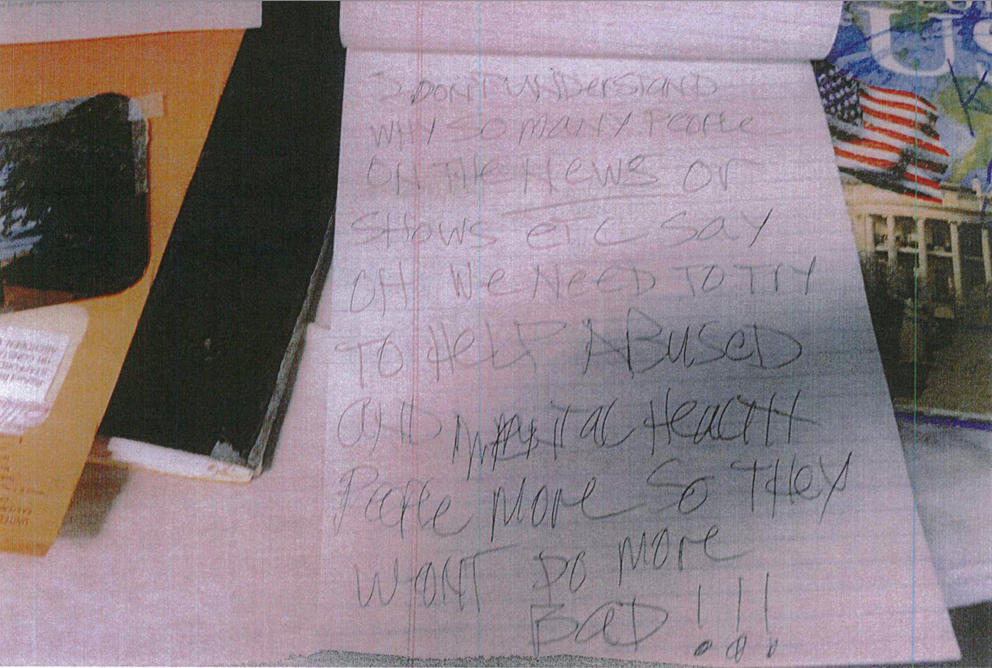

The Department of Corrections does at times conduct lengthy investigations after prisoners die. Reviews provided to Crosscut following a public records request included hundreds of pages of witness statements, investigators’ reports and photographs. Suicides, homicides and accidental deaths receive the most scrutiny.

The scope of investigation into medical deaths, though, remains unclear. Addressing the Legislature earlier this year, Corrections Department Chief Medical Officer Dr. Sara Kariko assured senators that the department does “review every single death that occurs, whether that’s an unexpected death or an expected death.”

When asked, the department declined to share the results of its recently created medical and mortality review efforts, describing the programs as too new. A public disclosure request for records related to those investigations remains outstanding.

In-house audits routinely give Corrections Department prisons top marks. The medical services division at the Monroe Correctional Complex received a clean bill of health from department auditors in 2017 at the same time prisoners there were dying under circumstances now under investigation by state health authorities.

Auditors, in a report obtained following a public records request, found the facility to be in compliance or partial compliance in every area related to health services. The prison infirmary was the first in the state to score 100% on the assessment, an accomplishment the magnitude of which, the auditors said, “cannot be overstated.”

“Across the hill,” the auditors remarked, describing the sprawling prison campus northeast of Seattle, “the health services team was found to be experienced, professional, friendly, cooperative and very helpful.”

The complex’s medical director, Dr. Julia Barnett, was put on leave months after the audit and has since been fired.

Speaking at the Legislature in January, Mary Jo Currey, then the assistant secretary leading the Corrections Department's health services division, walked a Senate committee led by Sen. Darneille through new department efforts to address failures of care and inmate deaths.

Darneille had introduced legislation that would for the first time require the department to regularly report the circumstances of inmate deaths to the Legislature and create an independent body to review deaths and near fatal incidents involving incarcerated people.

State law sets similar frameworks for bureaucracies managing the state psychiatric hospitals and child welfare system. Although it houses far more people than any other state agency, no similar oversight exists for the prison system.

Arguing for her bill in a lightly attended hearing that drew a dozen or so justice reform activists and a smattering of government workers, Darneille suggested that the state has a responsibility “to learn from those deaths and to honor the people who have died, in the sense that we don’t just go on without recognizing that our system can and should change.”

During the Jan. 14 hearing, Currey explained that the department launched a headquarters-based mortality review system in May 2019 and had recently rolled out a patient safety committee that would enable employees to report poor medical practices. As she described it, the latter panel, which includes all of the department’s senior health system managers, reviews any significant incidents to determine whether there was an “extreme departure of care.”

“I think some of the things we have in place are already there, and with a little bit of time we can show you some results,” Currey said.

Asked during the January Senate hearing whether she had any objection to formalizing the review process in statute, Currey said she would “probably like to have a little further conversation about that.”

By the time Currey was addressing the Senate, however, department administrators had already shuttered the patient safety review committee, said Dr. Patricia David, who served as the department’s medical director of quality and care management. David said complaints from prison medical directors, who manage the medical staffs at individual Corrections Department facilities, prompted the review committee’s closure in December.

Dr. Lisa Anderson-Longano, the department’s chief quality officer, said the review committee again began hearing cases on July 1. The department declined to say definitively when it had been shut down.

Communications director Janelle Guthrie said the department is “encouraging a culture where staff are more comfortable with reporting and discussing issues and concerns, with full transparency and the desire to use information to learn and improve.”

David started with the department in August 2018 and was instrumental in creating the safety review system. She left in March to join the Office of Corrections Ombuds. The review system’s purpose, David said, was to examine incidents involving possible patient harm; absent that committee, potential medical errors were not subject to formal review.

“Patient safety is the cornerstone of high quality health care,” David told Crosscut. “The purpose of reviewing cases … is to reduce risks, errors and harm to patients by understanding why, where and how adverse events are occurring, and making changes in order to prevent them.”

Currey left her leadership role with the health services division on March 4. Her position has been filled since by the department’s No. 2 administrator.

Ombuds office investigators reviewing the Jan. 1 death of an inmate who waited more than a year for cancer treatment that never arrived described both new oversight processes as flawed.

The sole issue cited in the department’s internal review was “provider-to-provider miscommunication,” according to the ombuds office. The postmortem review, ombuds investigators said in their July report, didn’t address the delays that led to the man’s death.

A pledge to continue

Darneille’s oversight bill did not proceed to a floor vote during the winter’s short legislative session. She said she is “quite certain” she and her colleagues will be coming back with legislation on the matter when the Legislature reconvenes.

Budge, the Seattle attorney, noted that other states, including Texas, have independent commissions that review deaths in prisons and jails. They can be effective, he said, in ensuring inmates survive their sentences and that families of those who don’t know why their loved ones died.

“I'm not here to say that people who are in prison deserve a higher level of care than people on the outside,” Budge said. “All I'm saying is that when a society makes a choice to lock somebody up, then you're making a choice to provide for their basic needs. And that includes basic, competent medical care.”

Cachero, the former inmate, said he has little faith that the Department of Corrections will protect prisoners or begin to reform itself. If change comes, he said, it will arrive “bill after bill,” as the Legislature fixes what he describes as a cruel, white supremacist penal system.

“I know that all of my brothers are suffering inside, and they are scared,” he said. “I’m not saying, ‘Oh, you poor criminals.’ Not that at all. But we're people. We're fathers and brothers, uncles and sons and all the rest of that.

“And if the system is what it's supposed to be, then everybody gets a chance.”

This is the third in a three-part series on prison health. Read the first two parts here.