While “Go West” was a popular 19th-century admonition, the West worked hard to create and maintain its whiteness. Black people were excluded from settling in Oregon. California toyed with similar laws, and while it banned slavery in its state constitution, Democratic politicians controlled the state and sought to make life difficult for Black people.

Chief among these were rules limiting schooling to whites only and preventing Black witnesses from testifying in court against whites. As one historian put it, that made it so the best Black man could not beat the worst white man in a court of law. If California couldn’t have slavery — and there were early attempts to establish it there — it could make normal life nearly impossible for Black folks.

By the late 1850s, some 4,000 Black Americans lived in California, with a thriving community of around 1,000 in San Francisco. Some made money in the gold fields, others as merchants. A Black church, a Black-owned newspaper and a strong civil rights organization had been formed, but the battles for justice were all uphill as federal offices, the courts, and the state government were controlled by anti-Black Democrats.

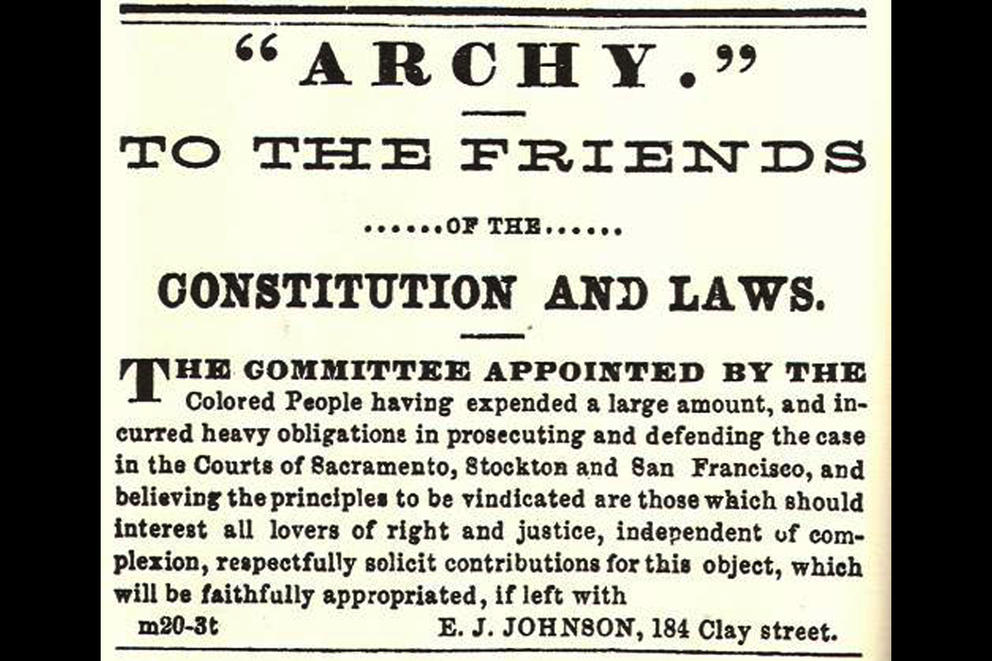

A case that ignited the community was that of a teenage enslaved man named Archy Lee who had been brought to California by his white enslaver. Lee was afraid his owner would take him back to Mississippi where they were from. The 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision ruled that fugitive slaves were property that must be returned. Archy Lee asked for his freedom in a “free” state. A legal battle royal took place. The Black community and white allies threw in to help Lee, but legal decisions went back and forth for months, with Lee held in various jails. If a non-fugitive could be enslaved in a free state, what meaning did the slavery ban in the California constitution have? Finally, a federal magistrate freed Lee. But while the battle for his freedom was won, it underlined the grave problems facing Black Californians. Would they still be free tomorrow?

Looking for safer haven, the community turned its eyes to the British colony of Vancouver Island, whose governor extended a welcome to Black immigrants. James Douglas, himself of mixed-race ancestry, said that Blacks in Victoria could own businesses, buy property, vote, become citizens, attend schools, and escape America’s racial bigotry. So in the spring of 1858, hundreds of San Francisco’s Black population pulled up stakes for Victoria.

Douglas wanted immigrants in part because the Fraser River and Cariboo gold rushes in British Columbia were drawing off workers. The colony needed bolstering against intruding gold-seeking white Americans too — Douglas was alert to losing territory to the Americans and border tensions were within sight of Victoria in the San Juan Islands.

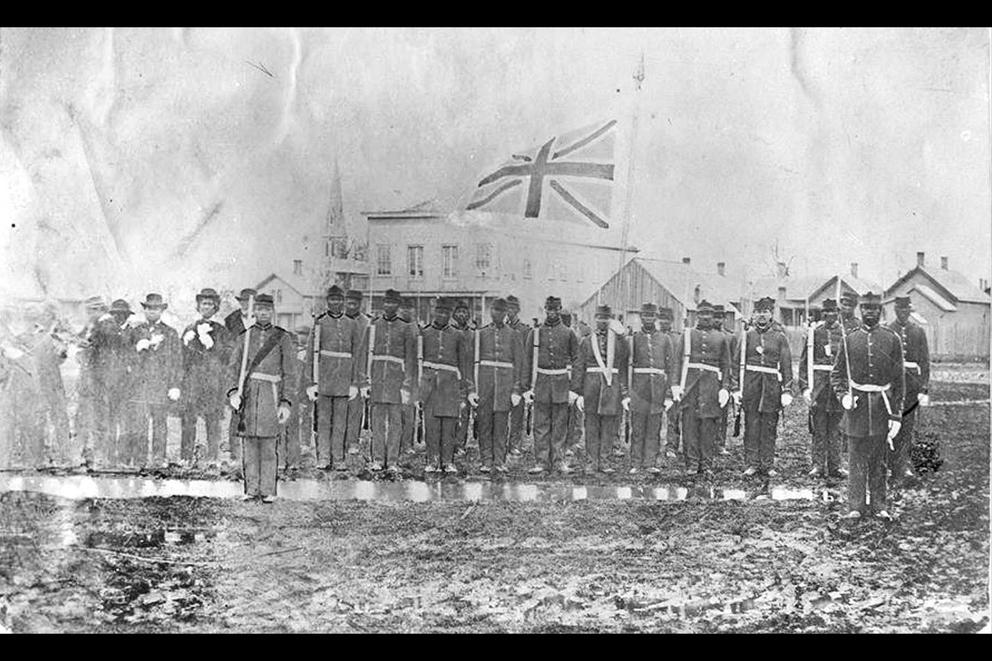

For their part, the Black immigrants were the first and largest influx of non-British immigrants to the colony. They came from all walks of life and quickly became key players in budding Victoria. Some were hired as policemen, and the province’s first militia was born, the all-Black Pioneer Rifles.

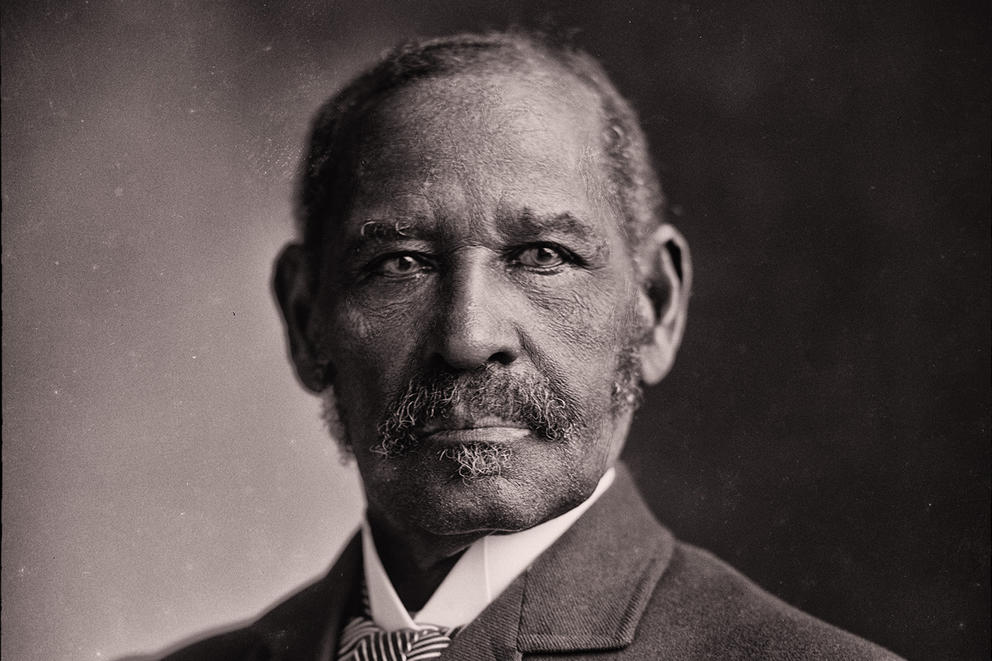

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs, a free Black businessman who had toured rural New York with Frederick Douglass and done well in San Francisco, became the first Black person elected in British Columbia when he was voted onto Victoria’s city council. Gibbs captured the promise Victoria offered: “I cannot describe,” he wrote in a memoir, “with what joy we hailed the opportunity to enjoy that liberty under the ‘British lion’ denied us beneath the pinions of the American Eagle.”

Gibbs had been a key player in freeing Archy Lee, and Lee joined the migration. So did the preacher and founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church of San Francisco, J.J. Moore. That church had raised much of the funds for Lee’s legal defense. Moore said the immigrants were looking for justice, suffrage and the right to “happy homes.”

Most of the immigrants settled in and around Victoria, but others moved out to farm, to settle on Salt Spring Island, or to join the hunt for gold in the B.C. interior. Some became British citizens. But integrating Victoria wasn’t easy. While the governor was welcoming, other residents were not, especially a large influx of white Americans who demanded segregation in churches and theaters.

The Union victory in the Civil War and the end of U.S. slavery signaled a new era for the expatriates. Many returned to the U.S., including Gibbs, who studied law and was the first elected Black judge in the U.S. in 1873, and later became U.S. consul to Madagascar. Moore wrote the history of the AME-Zion Church. And Archy Lee returned to California, where he died of fever in 1870.

The Black exodus his case helped trigger became an important chapter in U.S. and Canadian history, and its motivation was captured in verse by one Black Californian, a poet named Priscilla Stewart:

“God bless the queen’s majesty

Her scepter and her throne

She looked on us with sympathy

And offered us a home.

Far better breathe Canadian air

Where all are free and well

Than live in slavery’s atmosphere

And wear the chains of hell.”