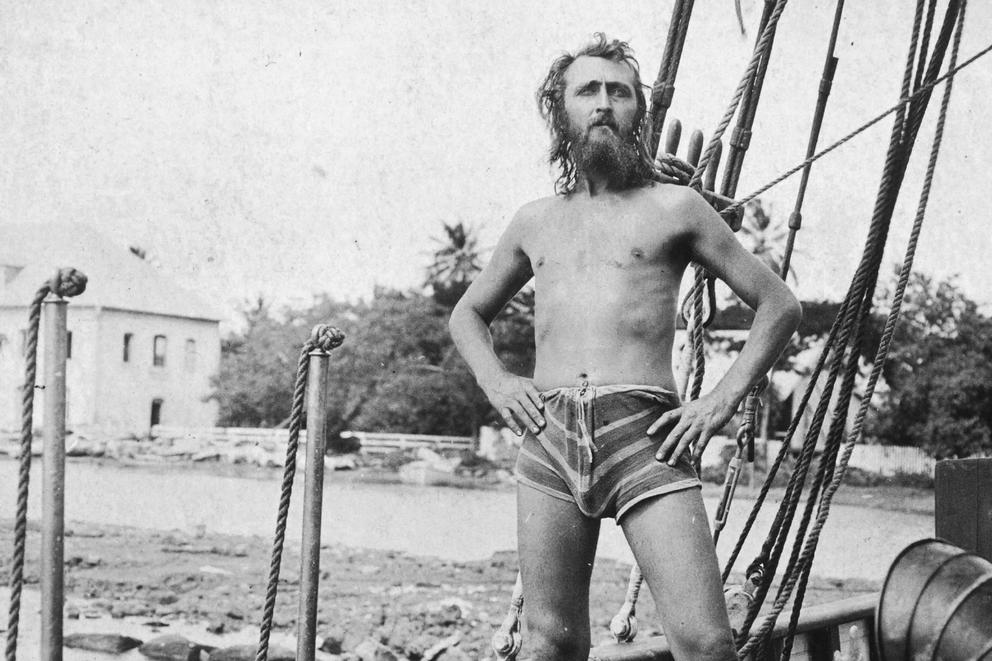

His biography sounds familiar. His actual name was Ernest Darling, though he was known more widely as Nature Man. He lived in Portland, where his father was a prominent physician. In the 1890s he went to California to attend Stanford, but dropped out due to ill health — he was scrawny and struggling. Traditional medicine — including his father’s ministrations — failed to work.

So, at 90 pounds of skin and bones, we went off to the Oregon woods. He shed his shoes and clothes — most of them anyway. He advocated eating only uncooked fruits and vegetables, nuts and berries. He shifted to warmer climes like California and wandered around near-naked there too. He became one of those Bay Area weirdos of which there have been so many. He met the famous author Jack London, who first saw him on the streets of San Francisco and later scampering in the hills outside Oakland.

“He was all sunburn,” London later wrote; “… he was a tawny man … all glowing and radiant with the sun. Another prophet, thought I, come up to town with a message that will save the world.”

And it’s true. Darling wanted a world in which people could be wild and natural, naked and healthy. In the late 19th century, gadding about barely clothed was enough to turn more than heads: It could get you arrested. So Darling decided to find more welcoming environs. In 1904 he tried Hawaii, but they were ready for him. The Hawaiian Star reprinted a San Francisco newspaper report about Darling, warning of his nakedness and strange lifestyle. In it, the 30-something young man tried to explain himself:

“I am not a religious crank, nor out to attract cheap attention to myself. I am an earnest student of good health and right conditions of living. I wish to discard clothing as rapidly as society becomes pure enough to stand it.”

After six months he learned that Hawaii wasn’t interested in what he was selling, which included near-nude pictures of himself. The sheriff charged him with obscenity and being a vagrant. So, facing jail time, he took a steamer for Tahiti.

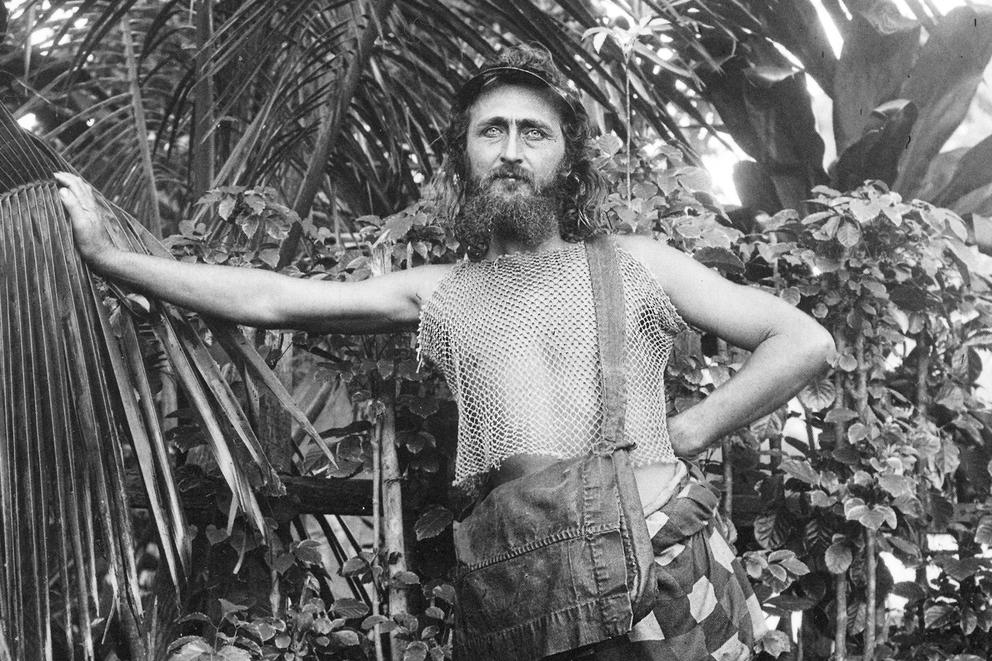

He made himself at home in the French colony, where he lived on bananas, honey, oranges and pineapples and had a grass hut and a small farm to tend. A travel writer who visited the islands described his conversation as “socialistic; his ideas of men living like monkeys was interesting, if queer.”

It was here that Darling became more famous because his old acquaintance from California, Jack London, came sailing into Pape’ete in his boat the Snark, a stop on his tour of the South Pacific with his wife in a custom-built boat.

Darling greeted London in an outrigger flying the red flag of socialism — and London sympathized. Darling shared his theories about levitation (it was possible) and how he would not need to sleep at age 100 and would be able to live on air alone.

London moved on, and Darling eventually did too. Nature Man left Tahiti and traveled in Asia and the South Pacific. Despite his health regimen, there was one affliction he couldn’t outrun: In late 1918, the influenza pandemic swept Fiji. Fresh air, fruit and sunshine were no vaccine for the Spanish flu.

Nature put an end to Nature Man.

But wait: Darling wasn’t the only Nature Man in the news at that time. There was another — not an imitator, but a man who went into the woods around the time Darling was gamboling in Tahiti. He wasn’t doing it for his health, but to prove the superiority of the modern white man. And unlike Darling, Joseph Knowles became a major national sensation.

Knowles said that he could live — without clothes or food — in the woods for 60 days. “I wondered if the man of the present day could leave all his luxury behind him and go back into the wilderness,” he said. Knowles was inventing the kind of spectacle that we see today on “reality” TV. The press lapped it up.

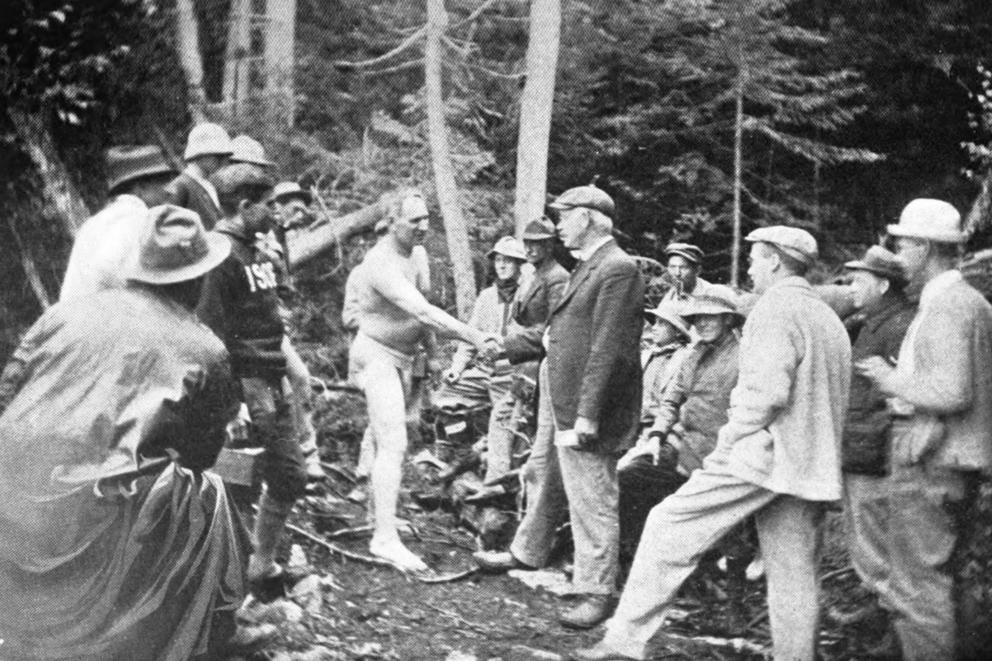

Nature Man Knowles went into the Maine woods in a loincloth, weaponless, and eventually came out weeks later wearing a bearskin and claiming to have survived by his wits and woodcraft alone. A book of his adventures, Alone in the Wilderness, followed, as did movies and speaking engagements across the country. In fact, he later married a longtime friend, Marion Humphrey, at Tacoma’s Pantages Theater during a run there.

In the early 1900s there was a so-called crisis in white manhood, when increasingly urbanized Americans stood accused of being soft. Soon after Joe Knowles’ sojourn in the Maine woods, he faced accusations that he had cheated, that he’d lived in a cabin and that the bearskin he wore had a bullet hole in it. Could it be that Knowles was a fake?

So Knowles went to the West Coast to recreate his stunt in the Siskiyou Mountains of southern Oregon. This time he brought scientists. One of these was anthropology Prof. T.T. Waterman of the University of California, and later the University of Washington.

Waterman wrote, “When [Knowles] walks into the woods alone and unarmed to live there for a month or more, he places himself where the first naked man walked the earth, and it will be of interest to see what kind of implements he uses and in what order he invents them.”

In the summer of 1914, Knowles entered the wilds outside of Grants Pass, Oregon. He was sent off by the press and his watchers, who would stay in regular touch. To report his progress, Knowles passed out notes written in charcoal on bark. This time he lasted about a month without any apparent fraud.

Unlike in Maine, when he came out of his Oregon stunt, the public’s attention had been diverted by the start of World War I.

Billed as the “modern Adam,” Knowles toyed with going out again, this time paired with an Eve — he called her “Dawn Woman.” He declared that modern society women “with … corsets, tight shoes, and her diet” could not sustain themselves in “primitive conditions.” He was confronted in California by another prospective Eve named Louise Hescock. “I … would like to prove to him he is wrong in his opinion of we women,” she said. Alas, that test apparently did not happen.

Knowles wound up living in Seaview, Wash., in a beach cottage described as “early American flotsam.” He became a well-known southwest Washington artist. He died in 1942, his Nature Man celebrity largely forgotten.

Accusations of fraud, disease, jail time, fleeting fame: For these Nature Men, getting back to nature wasn’t as easy as it seemed.

For more on this story, listen to the Mossback podcast: