We locals all know about the fair’s stars: a focus on the Space Age, the Needle, the “Space Gothic” arches of the Pacific Science Center, the Bubbleator and the paraboloid-roofed Coliseum, now Climate Pledge Arena. They’re like old friends to Seattleites, part of the civic center that is a legacy of the midcentury exposition on Lower Queen Anne.

But the fair might have been radically different from the fair we remember, in theme, physical layout and legacy. Seattle could have had manmade islands, a waterfront boardwalk linked by monorail, an Elliott Bay freeway, a vast domed stadium years before the Kingdome was built. These are some of the legacies that didn’t happen.

The fair was under consideration from 1954 until it opened in April of 1962. The process was one of big dreams, pragmatism, politics, controversy and multiple agendas. There were many stumbling blocks along the way: lawsuits, budget alarms, arguments over sites — all the usual stuff that attends such big civic projects.

Consider for a minute the context. The last U.S. fairs before the one in Seattle had taken place before World War II. Many questioned whether the modern world had moved on from such extravaganzas. In 1954, Disneyland was breaking ground in Southern California, which Walt Disney described as “a combination of world fair, a playground, a community center, a museum of living facts, and a showplace of beauty and magic.” Some wondered if a permanent amusement park like Disney’s had rendered fairs obsolete.

Yet, at the same time, other cities were contemplating holding world’s fairs, including Portland, San Francisco, San Diego and New York. The news in 1954 that Portland was considering a fair lit a fire under Seattle planners who did not want to be bested by a regional rival. Portland’s fair turned into a local history-oriented festival, and New York’s took place two years after Seattle’s. The other fairs dropped by the wayside. Fair schemes have a high failure rate, turns out.

Operating out of a sense of opportunity and the perceived need to prove Seattle was a great West Coast Pacific port, the state voted to study a world’s fair in 1955. When Seattle voters soon after approved bonds for a long-desired civic center, the two ideas melded into one — a fair with a civic center legacy. That gave fuel to the effort. This fair would leave a permanent mark.

But what would it be? The first idea was that it would be a trade fair featuring local products and a Pacific rim focus. It would be held in 1959, a half-century after the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909 and would commemorate that event. That evolved into a “Festival of the West” concept featuring the burgeoning Western region. A foreign trade center would be built and have offices to house all the foreign consulates. The port would take center stage as a key international economic engine.

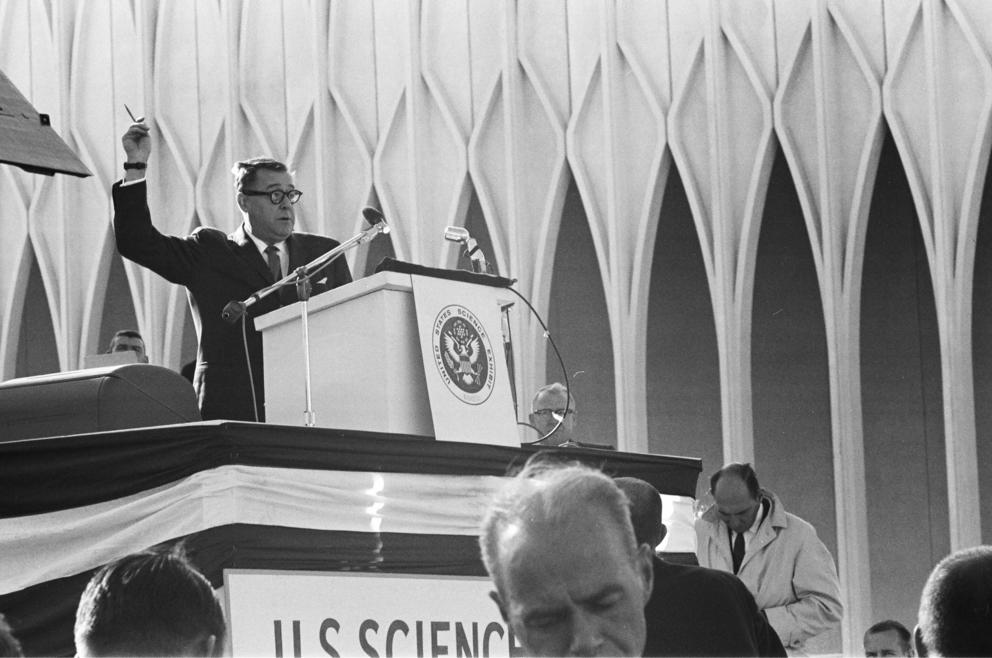

By the late 1950s, it had morphed again, and the date of the fair slid back into the early ’60s. In 1959, then-President Dwight Eisenhower issued a proclamation for the “World Science Pan-Pacific Exposition.” The federal government was willing to kick in major funding for a science-oriented fair, fueled by Cold War concerns about beating the Soviets. A major expo was held in Brussels in 1958 and convinced U.S. scientists that we needed better promotional efforts for public science to counter the Russians. A futuristic theme appeared: It would be called the Century 21 Exposition.

Visions of the fairs that didn’t happen are most vivid in the concepts floated — in some case, literally floated — as consultants and engaged Seattleites, and civic boosters became caught-up in the planning and dreaming.

For example, the West Seattle Commercial Club wanted the fair to be located off Duwamish Head, where the river feeds into Elliott Bay. They suggested building a new 440-acre artificial island between there and Alki with a massive off-shore bulkhead and mounds of sand. The inshore waterway that would be created could be a marina. An amphitheater could be dug into the hillside. If the island could be built for $1 million, advocates argued, it would be cheaper than acquiring land in the city.

A kind of consolation prize for West Seattle, as possible locations shifted to mainland Seattle, was the suggestion to erect a sculptural “stainless steel needle” at Duwamish Head as a symbol for the fair. The Bremerton Sun editorialized against it, saying “phooey.” The newspaper wrote, “We just don’t fathom how a thin shaft of steel can symbolize ‘the good life and hope for all mankind in this new atomic age.’” The editorial writers dreaded having to look at modern art every time they took the ferry.

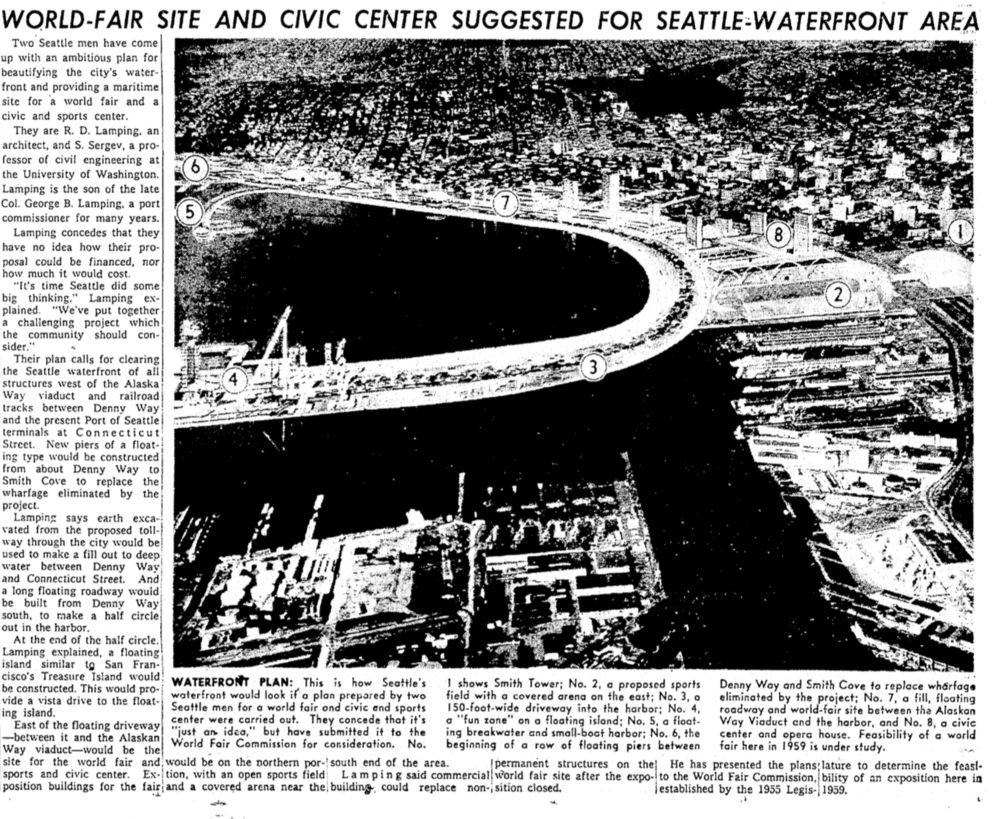

The showcasing of the bay and Puget Sound factored into other grand fair proposals. One was put forward by an architect, R.D. Lamping, and a University of Washington engineering professor, S. Sergev. It was splashed across newspaper pages. They proposed a massive remaking of the waterfront: Demolish everything on the central waterfront and replace the wharves with floating wharves further along toward Smith Cove. Keep the Alaskan Way Viaduct, but everything to the west would be the temporary fair site, and athletic fields, replaced afterwards by commercial buildings. The capper was a sweeping arc of floating “driveway” connected to a “floating island” off West Seattle. Lamping said he had no idea what his concept would cost, but “it’s time Seattle did some big thinking.”

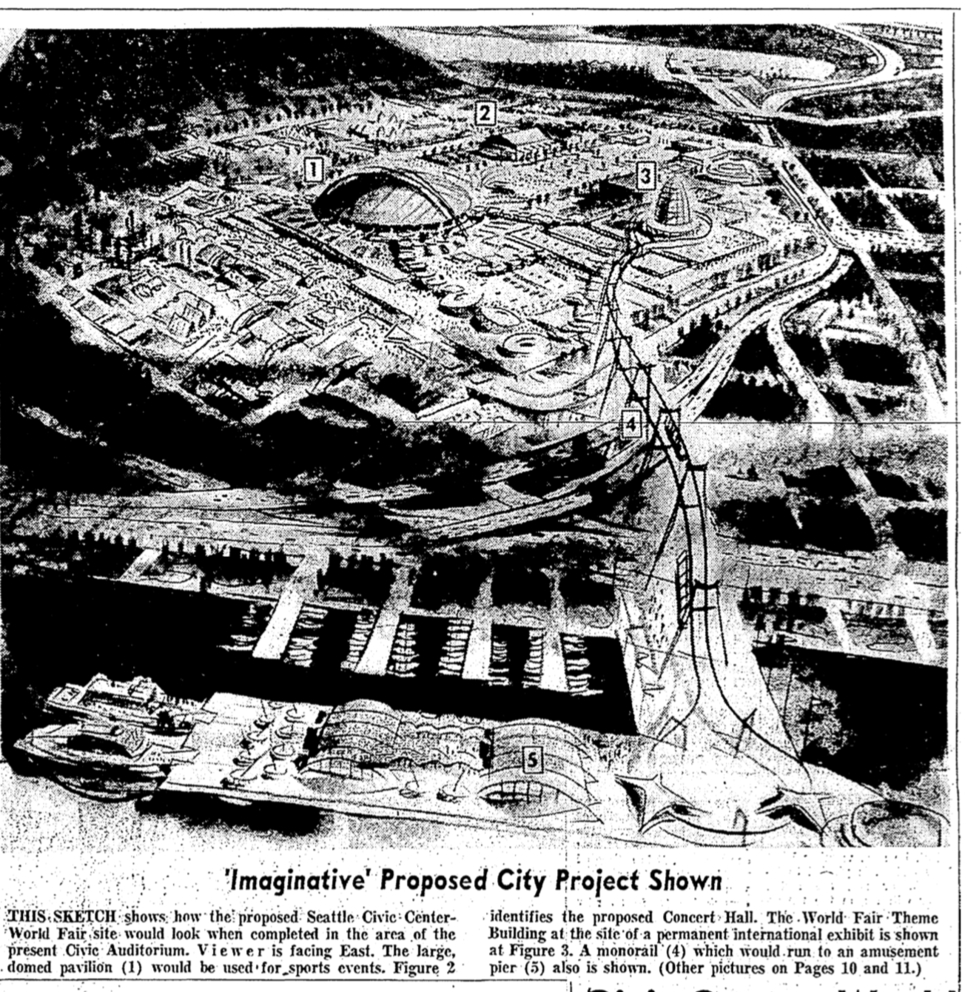

The linking of the fair to the waterfront with floating structures was not simply a crackpot idea. In 1957, the Civic Center Advisory Committee and the state’s World’s Fair Commission, released a plan developed with the Stanford Research Institute think tank and a cadre of esteemed architects, including landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, NBBJ’s Perry Johanson and the Seattle-trained Minoru Yamasaki, who designed the fair’s Federal Science Pavilion and, later, New York's World Trade Center Towers.

Their concept showed a massive fair site on south Queen Anne, much larger than the eventual 74 acres obtained for the actual fair and Seattle Center. Memorial Stadium was to be demolished and replaced by a huge, domed indoor sports “pavilion.” A monorail connected the fairgrounds with the waterfront, where a new Atlantic City-style boardwalk complex, an amusement zone and a new marina filled the area roughly where the Olympic Sculpture Park and Myrtle Edwards Park are now.

The monorail appeared to depart from a cone-shaped structure that was described as a “World Fair Theme Building.” An alternative idea to the monorail was a pedestrian bridge lined with shops and stalls, like a modern-day Ponte Vecchio connecting to the waterfront. The ambition went way beyond fair and civic center, imagining a 21st century waterfront largely for recreation and tourism.

Countering the dreamers were the naysayers, who thought the fair was just a bad idea. No fair at all was one of the futures considered. Attorney Alfred Schweppe sued over the fair. He opposed mingling the civic center bond money with the fair and complained about the overall cost. In a letter to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, he concluded: “Frankly, while there is no objection to dreaming, it would in this case be wise to come down to earth, drop the whole World Fair idea, and concentrate on planning to provide a great public stadium adequate for big-league baseball, professional football, and other great public events….” The Kingdome eventually addressed that issue from its opening in 1976 to 2000, when we blew it up before it was paid for.

Perhaps the grumpiest fair critic was Seattle’s Catholic archbishop, the Rev. Thomas A. Connolly, who, upon being dazzled by a visit to the 1958 Brussels fair, came home and could imagine none such for Seattle. “[W]e run the risk of becoming the laughingstock of the United States with the small Woolworth’s operation presently being envisioned on a few blocks of property with no parking space and little room for national and international exhibits.”

A “Woolworth’s” fair was precisely what Seattle organizers feared, so they countered with hard work and optimism. If the archbishop’s outlook was a glass half-empty, Sen. Warren G. Magnuson, who was key in obtaining federal funds for the fair, had a glass half-full response, calling the smallish expo a “jewel box fair.” That fair is the one we remember and benefit from today. A small-scale expo, but one that was profitable, unlike most fairs, and left us with civic treasures we still value.

The fairs we don’t remember offer us a way of checking our progress. Did we do better than we might have? Are we glad we didn’t build an Atlantic City on the waterfront, or a floating freeway on Elliott Bay? I think we got the future more right with our world’s fair than we could have.