For those of us who live in the Northwest, it has also been an unsettling reminder that we live at one of the centers of potential conflict — a ground zero if an all-out nuclear war between the United States and Russia should erupt. We would likely be nuked off the map very early in that exchange.

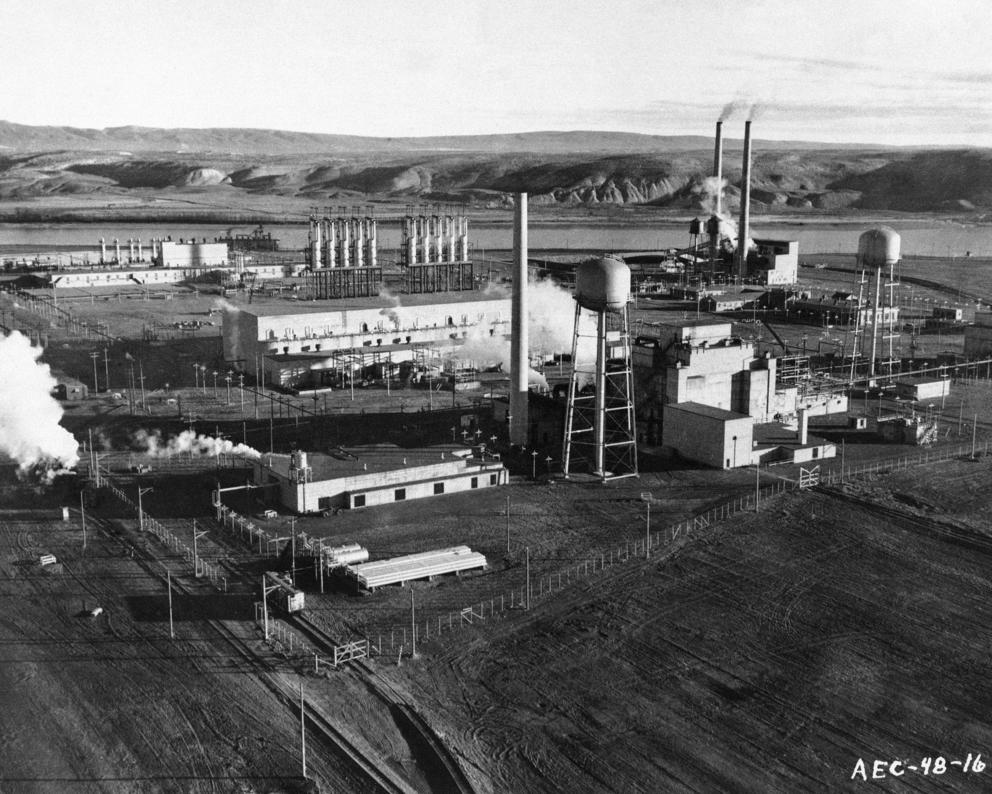

Seattle author Steve Olson knows this well. His book, The Apocalypse Factory, details the history of Hanford, the nuclear production complex whose role in the 1940s Manhattan Project was to churn out plutonium for the first atomic bombs. It was Hanford plutonium that fueled the bomb the U.S. dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945, the last time a nuke was deployed against people. During a recent interview on the PBS program The Open Mind, Olson reminded us that not only is the Puget Sound region home to the largest single stockpile of nuclear weapons in the world, at Bangor in Kitsap County, but, “All of our current nuclear weapons have plutonium inside them that was made at Hanford.” The site is decommissioned but its legacy lives on, and so do long-term problems with radioactive and chemical contamination.

From the very beginning, Washington state has been at the center of the creation of nuclear weapons, thanks to the Columbia River, Grand Coulee Dam’s hydropower, and the lonely desert of Eastern Washington where Hanford’s reactors were built to feed the atomic arsenal.

The threat of nukes is very real, Olson reminds us. But unlike a threat like climate change, which is rolling out over decades, nuclear war, he says, “remains capable of destroying human civilization in an afternoon.”

All this frightening stuff has me feeling scared, but oddly congruent with my younger self. Sixty years ago, I was 8 years old and attending John Muir Elementary School in Seattle’s Mount Baker neighborhood. I remember the spooky wail of the Beacon Hill air raid siren every Wednesday at noon. I remember the Soviet premier threatening to “bury” us. I clipped the pages of Life magazine and made a scrapbook with pictures of Nikita Khrushchev, Fidel Castro and President John F. Kennedy.

The early 1960s were the peak years for building fallout shelters. People put “bunkers” in their yards and converted storerooms in their home; the government even built a “community” bomb shelter under Interstate 5 near Seattle’s Green Lake neighborhood. It seemed then that the Cold War could turn very hot at any moment.

At the time, I thought my parents were committing familial malpractice by not building a bomb shelter. I remember one house-hunting trip with my mother when we saw a home with a fully stocked shelter. Why, I begged, can’t we have one? My father said we could use his basement darkroom, but even then I was dubious that a room full of chemicals and empty beer bottles would offer protection.

That year, the Cold War played a role at the most upbeat event of my lifetime up to then: the Seattle World’s Fair. The science themes of the fair were picked because of the “Space Race” spurred by the Soviet launch of the first satellite in the late ’50s. The Space Needle was a Cold War statement that countered the Soviets. It was built at the same time as the Berlin Wall. Labor leader George Meany called it a “towering monument to the aspirations of humanity,” while saying that the Berlin Wall represented “the basic cruelty of the Communist conspiracy and its utter disregard for human life and values.”

University of Washington Professor Emeritus John Findlay, in his book Magic Lands: Western Cityscapes and American Culture After 1940, said the fair, which will see the 60th anniversary of its opening on April 21, was designed to appeal to the 1960s “nuclear family” and to largely sell people on suburban aspirations. It imagined a future of happy consumerism for mom, dad and the 2½ kids.

But Findlay says there were some dark notes. One was sounded in an exhibit shown to visitors who took a transparent spherical elevator — the Bubbleator — to the upper level of the Washington State Pavilion. There visitors saw multimedia visions of the “World of Tomorrow.” The exhibit, titled “The Threat and the Threshold,” showed images of the imagined aftermath of World War III, including a desperate family in their “grimly well-ordered fallout shelter.” The choice of the happy ’burbs or total devastation was ours to make.

Though the fair, with its tasty Belgian waffles and the promise of atomic-powered cars, sought to distract us from nuclear fears, those fears were amplified by events that unfolded as the event drew to a close in October of 1962. President Kennedy was supposed to attend the closing of the fair, but he canceled his appearance because of a “cold.” That was a fib. He was in fact facing off with the Soviets over their deployment of missiles close to the U.S. mainland in Cuba, a confrontation not yet made public. The Cuban missile crisis almost triggered a nuclear blowup — the closest we’ve probably come so far to an all-out atomic apocalypse.

In his PBS interview, Steve Olson reminds us that we could have time to possibly engineer our way out of global climate disaster, though it would take a worldwide commitment. The prospect of avoiding nuclear annihilation relies on fewer nations and leaders to come to an agreement. The world’s nuclear arsenal of some 13,000 nukes is controlled by, roughly, nine men, he observes.

That is both frightening, and possibly encouraging. Mutually assured destruction has so far kept anyone from pushing the red button. Further success depends on the nine individuals representing the nine nations with nuclear weapons, any plans they have to “update” their arsenals and how many others will seek to join them in the nuclear club.

Yet, during the pandemic there's been an exhibition of self-destructive, anti-science behavior. That, in addition to the power of fake news and now Russia’s instigation of a major European land war, has shaken my faith in nuclear restraint’s slender thread. I hope, as in 1962, my 8-year-old self’s worst fears will be unfulfilled.