Today, flying Confederate flags over a major street in the city would incite howls of protest. Last year, a Confederate memorial in Lake View Cemetery was vandalized and toppled by unknown persons in the summer of 2020.

But things were different in Seattle during the first half of the 20th century. Thanks to plays, books, movies and propaganda about the Old South, many Seattleites embraced a view — promulgated by Southerners and white supremacists — that sought to rewrite the history of the Civil War and the enslavement of Black people. While Seattle was far removed geographically from the epicenter of hostilities, the post-Civil War culture war flared up here, underscoring just how susceptible Seattle was to the bigotries of the day.

In 1940, the Confederate flag moment was caught briefly on a color home movie. Crosscut stumbled upon the historical footage during production of a Mossback’s Northwest episode about the Seattle Freeze. After the episode aired, a few sharp-eyed viewers caught a glimpse of the Confederate battle flag amid red-and-white-striped banners and wanted to know why the flags were flying there.

A closer review of the footage revealed scenes from the Jan. 25 opening of Gone with the Wind, the much-anticipated MGM film based on the 1936 bestselling novel by Margaret Mitchell. The video accorded with newspaper accounts of the premiere. At least one newspaper review confirmed Confederate flags were flying along and above Fifth Avenue to promote the movie. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer’s critic, J. William Sayre, pronounced the movie's local premiere a triumph. He wrote, “Gone with the Wind came with the snow, as it happens. Outside of the Fifth Avenue [Theater] up and down the street, the Stars and Bars of the Confederacy proclaimed the arrival of the Civil War epic.”

Sayre went on to extol the virtues of the Old South that were lost in the Civil War. “Gone with the Wind pictures a grandeur that is no more," he wrote, "the near feudal estates of the Old South before the war; proud Georgia families of wealth and distinction, with their hospitable mansions, broad acres, beautiful women and chivalrous men and the faithful old mammies who served them.” There’s no mention of enslaved people, treason or secession. But Sayre does note the “pillaging” of the South, the burning of Atlanta, and the “carpetbaggers” — an epithet for Yankees who helped to usher in Reconstruction. There was little question where Sayre’s sympathies lay.

But he was not alone.

Gone with the Wind was controversial in its time. Critics labeled it “propaganda for the Lost Cause,” nothing more than whitewashed mythology about the South, the war and Reconstruction. But the film was incredibly popular — and so it remains. At the time, Seattle’s mainstream critics embraced its vision of the Old South as a kind of Confederate Camelot. The Seattle Times’ reviewer, Richard E. Hays, wrote that the movie’s portrayal of the effect of the Civil War “on the honor, chivalry and civilization of the Old South is a profoundly stirring drama.” There was little in Seattle’s daily press coverage to indicate suspicion, let alone revulsion, about the film and its historical accuracy.

The film was also the subject of consideration in the Seattle-based Northwest Enterprise, the region’s preeminent Black newspaper at that time. An unsigned column in January of 1940 noted: “Since its premier[e], organizations and prominent individuals have denounced it as an indictment of inter-racial good will, and a concerted boycott will no doubt be launched against all theatres showing the picture.

“We are anxious to see ‘Gone with the Wind.’ We won’t like it because of the many ‘digs’ it takes at the Negro, but we WON’T condemn it. We won’t condemn it because that would be ‘locking the door after the horse has escaped.’ We believe all protests against the picture [should] have been made long before it went into production.”

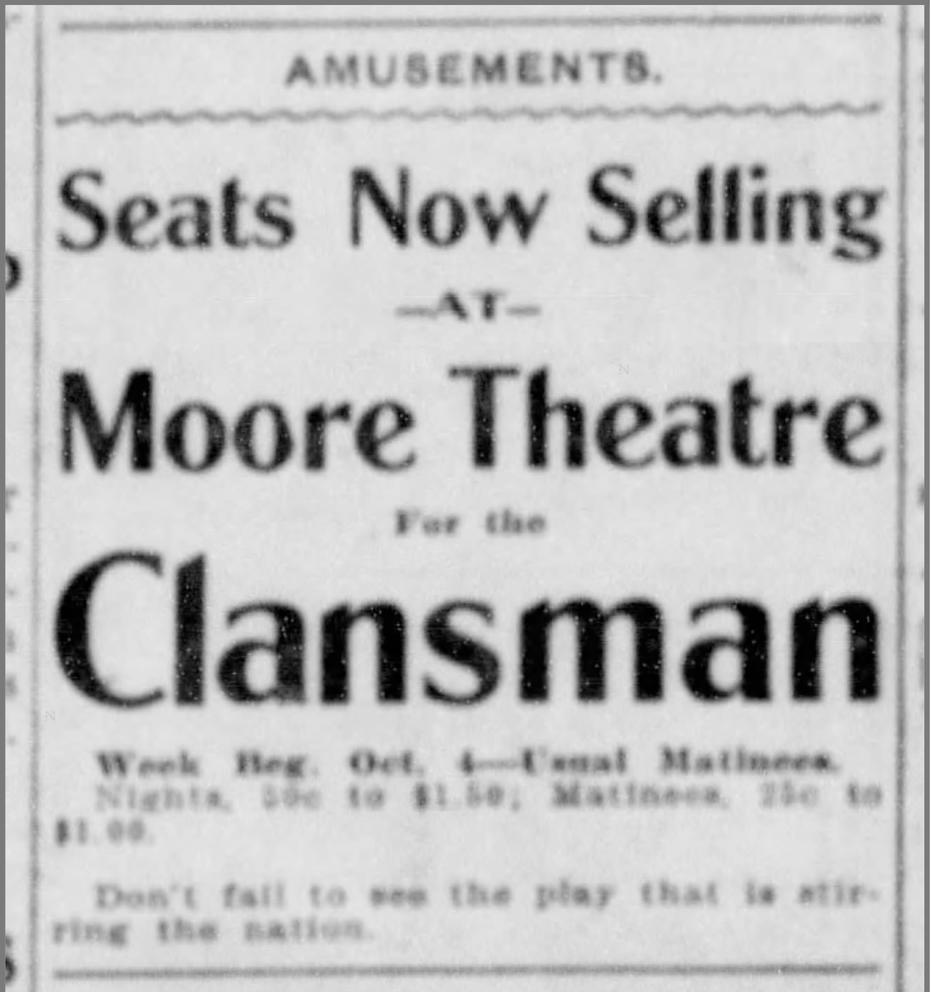

Before Gone with the Wind, other works aimed at remolding postwar opinion and history were shown in Seattle. Margaret Mitchell was inspired by author Thomas Dixon Jr.’s books, including The Clansman, the stage version of which opened in Seattle in October of 1908 at the Moore Theater. The book and play made heroes of the Ku Klux Klan, and Black characters, acted by whites, appeared as stereotypes in blackface. “The Ku Klux on stage,” the P-I announced ahead of the play’s opening.

The show received pushback in many cities where it played. Members of Seattle’s Black community attempted to halt its staging here, but were hindered by having to post a $1,000 bond to “indemnify The Clansman against losses," reported the Seattle Star. That was apparently too much for the objectors to raise. Meanwhile, talk of a protest outside the theater generated a strong response from the chief of police. He warned, according to the Star, that protesters would be met by “an ample force of uniformed policemen.”

“There will be no trouble,” pledged the chief.

Horace Cayton, Jr., editor of the Seattle Republican, the city's most successful Black-run newspaper, weighed in when The Clansman drama arrived on the West Coast. Cayton, born enslaved, was married to and ran his paper with Susie Revels Cayton, whose father, Hiram Revels of Mississippi, was the first Black U.S. Senator and an icon of Reconstruction.

“There is no doubt but that the play … encourages, yea, even produces color phobia in its most violent form and should not be put on any exhibition in any civilized country,” Cayton wrote.

Still, banning the production when a majority of a city wanted to see it would result in “free advertising,” he concluded.

The Seattle Times' “drama department” seemed to agree. They refused to review The Clansman during its successful run. After the play closed, the newspaper declared it “Unclean” and “utterly degrading” and called its theme “revolting.” Reviewing it, the paper maintained, would have just generated controversy that would have filled “unclean coffers.”

The P-I, on the other hand, had no problem hyping the play. In one report, it wrote that it “pictures the days when courage, self-sacrifice and heroic deeds removed the fetters that held the south in bondage after the war between the states.” In other words, the states of the Confederacy were the victims, not the perpetrators, and that postwar life was tough until the Ku Klux Klan restored order and freed whites from “bondage.”

Works extolling the virtues of the Confederacy did not stop there. Seven years later, in 1915, The Clansman had become the basis for a cinematic blockbuster that soon arrived in Seattle. D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation opened that year at the Clemmer Theater (“Seattle’s Best Photoplay House”), located on Second Avenue between Pike and Union Streets downtown. If The Clansman play was popular, Birth of a Nation helped usher in a new era of powerful cinema promoting white supremacy with technically stunning film innovations. It was not only a cinematic hit, but played a role in stirring up the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, which swept through Northern states, including Washington and Oregon, in the 1920s.

In The Seattle Times, a large ad for Griffith’s film was bordered with images of KKK nightriders. The paper seemed to have done a complete turnaround from its disgust at The Clansman: “We cannot see how anyone who has seen this feature can criticize it. Colored people have no objection to it and certainly ministers have none. … It is a masterpiece without a flaw.”

Despite The Times' hyperbole, the movie was not without its detractors. The NAACP worked hard to have it banned upon its release. In 1915, James Weldon Johnson, the first Black head of the historic civil rights organization, estimated the potential damage that would be done by Birth of a Nation: “‘The Clansman' " did us much injury as a book, but most of its readers were those already prejudiced against us. It did us more injury as a play, but a great deal of what it attempted to tell could not be represented on the stage. Made into a moving picture play, it can do us incalculable harm.”

The late film critic, Roger Ebert, wrote this assessment: “The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like [Leni] Riefenstahl’s [pro-Nazi] The Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil.”

By the time Gone with the Wind premiered in Seattle, many communities in the city had been groomed for Southern sympathy. The film was a kind of sanitized version of Birth of a Nation; it removed the Klan and cut the N-word from its script, largely under pressure from the film’s Black cast. And it received some positive notice in the Black press for employing actual Black actors, not whites in blackface.

But the daily papers here routinely followed the doings of Confederate sympathizers. The United Daughters of the Confederacy, for example, was a national force that lobbied for, among other things, the Jefferson Davis Memorial Highway system. In 1940, the year Gone with the Wind premiered here, the Washington Daughters successfully got the state to allow markers designating Highway 99, from Blaine to the Oregon border, as part of the system honoring the Confederacy’s president.

Newspapers regularly carried notices of the local “Robert E. Lee Chapter” of the Daughters' meetings, tea gatherings, lectures, a state convention and banquets. In 1939, a Daughters-sponsored show featured a performer of “Negro folklore,” Miss Virginia Bassett, who, according to the P-I, “promises to be as entertaining as the chuckling and sometimes wistful humor of the Negro race itself.” In addition to singing spirituals, the paper wrote, Miss Bassett “will present character sketches from ‘Gone with the Wind.’ These are said to be presented most vividly as they are so parallel with her own plantation experiences.” Bassett was a white woman from Alabama.

Every year on Lee's birthday, the Daughters organized a ceremony at the Confederate memorial, since toppled, in Lake View Cemetery. Often appearing on such occasions was Seattle's last known Confederate veteran, Joseph Bell Pritchett, who fought during the Civil War in Sherman’s March to the Sea in Georgia. He moved to Seattle shortly after World War I and later died, in 1945, just shy of 100. On his 94th birthday, he is said to have remarked of the Confederate Stars and Bars flag that he kept with him, “I don’t yield to anyone in my love, devotion and loyalty to America. But if feeling a tender sentiment for the flag of our lost cause makes me an unreconstructed rebel, I guess I am one.”

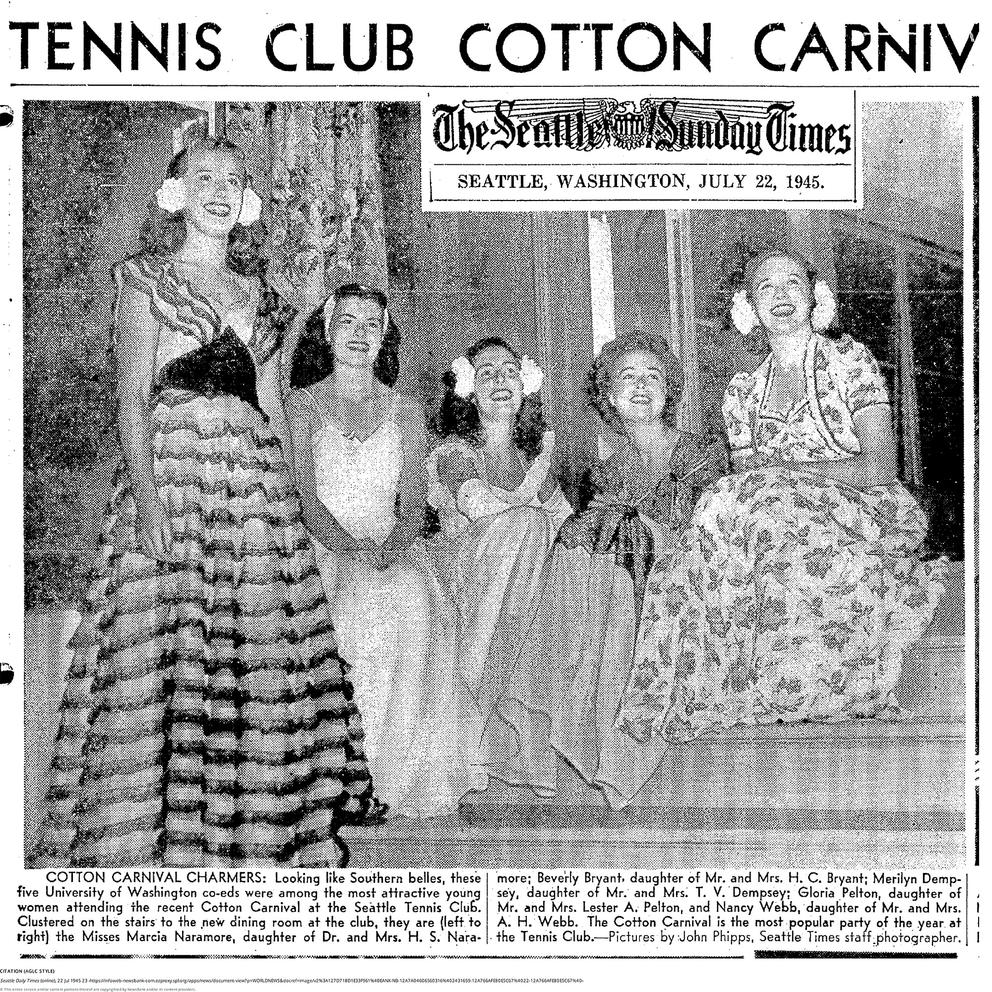

During that era, so-called "Cotton Carnivals" were held around the country, in which women showed off fashionable gowns, sometimes in the style of Southern belles made popular by the Gone with the Wind plantation aesthetic. One such carnival was held in 1947 at the Seattle Tennis Club on Lake Washington, which then excluded Blacks and Jews. A 1944 travel article in The Times asked, “Do You Know Dixie?,” and purported to set the record straight on the South for apparently ignorant Northerners. The war “was fought over states’ rights, not the slavery question,” it contended. “Gone with the Wind depicted the era wonderfully.”

Seattle’s history of racism, redlining, segregation and other forms of exclusion date back to the region’s first days of exploration and settlement. But the 1930s and ’40s demonstrated the power of popular culture to help rewrite the history of the South, to influence Northerners into adopting a nostalgic sympathy and “tender sentiment” for white enslavers and racism’s enforcers.

This was a phenomenon that Booker T. Washington had warned publisher Horace Cayton Jr. about on Washington’s visit to Seattle in 1909, according to a memoir by Cayton’s son, Horace R. Cayton. His father, then a successful newspaper publisher, celebrated that Blacks in Seattle were largely free of barriers and prejudice encountered in the South and thought more should leave the South behind.

Washington cautioned Cayton Jr. about the spreading of the Southern white narrative as Blacks migrated north. “The South was defeated, not destroyed; today it is influencing more of the country than you are perhaps aware,” Washington reportedly said. “I sincerely hope, Mr. Cayton, that insanity does not overcome you here in the relative freedom of the Northwest. I hope that the infection of Negro prejudice does not spread to this part of the country. If it does, you may find out that you have been living in a fool’s paradise.”

Confederate flags flew over a downtown Seattle street in 1940 to sow white unity while rewriting the past with the power of Hollywood. It seems to have worked. Seattleites who objected to The Clansman in 1908 were largely unheard when the story was later repackaged as the innovative silent film Birth of a Nation. A quarter century later, many in Seattle embraced an even more glamorized big-screen version of that narrative in Gone with the Wind.

By 1940, the old Stars and Bars must have seemed to many like just another American flag.

History is a political battleground. While Confederate statues and monuments have been removed in the South and elsewhere, the Confederate battle flag enjoys a renewed life, often seen defiantly unfurled in protests across the country, including in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol during the Jan. 6 insurrection. We argue with one another over what history is to be taught in schools, over who controls the narrative.

Those Confederate flags that flew over Fifth Avenue underscore the power of the false narratives and symbols still with us today. Located in a once remote corner of the country, Washingtonians have often viewed themselves as somewhat separate from national politics — a place apart, perhaps even better than anywhere else. Many early settlers came here to avoid “sectional” and racial conflict. Yet not only did many arrive with longstanding prejudices, they proved that we were, and still are, vulnerable to modern propaganda campaigns and the flags they fly under.