Jon Hutchings resigned in lieu of termination in October 2022, just one day before a third-party investigator interviewed three female employees who reported Hutchings had made sexual comments to them or touched them inappropriately while at work.

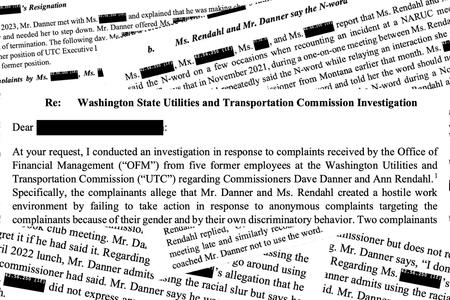

But county leaders never formally disciplined Hutchings or adjudicated the complaints. And they helped him get a new job, writing a favorable “letter of introduction.”

“It has been a pleasure working with Jon and I am very confident that he will serve your organization well,” the letter concludes, signed by the county executive and deputy executive.

As a legal condition of Hutchings’ departure, county leaders also agreed not to disclose information about his misconduct to future employers. Hutchings now runs the Public Works department for Lynden, a city of about 16,000 people 15 miles north of Bellingham. He did not respond to a request for an interview.

Lynden’s city code requires department heads to be appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the city council. Mayor Scott Korthuis did not respond to multiple calls and emails, and City Administrator John Williams declined to say how much they knew about Hutchings’ past behavior when the city hired him, referring to it as a “personnel matter.”

This story is part of Cascade PBS’s WA Workplace Watch, an investigative project covering worker safety and labor in Washington state.

Cascade PBS reached out to Whatcom County Executive Satpal Sidhu, Deputy Executive Tyler Schroeder, and current Public Works Director Elizabeth Kosa, who served as assistant director before Hutchings resigned. None responded to interview requests for this story.

Whatcom County spokesperson Jed Holmes wrote in an email to Cascade PBS that the county is committed to investigating allegations of inappropriate workplace behavior, but officials did not respond to detailed questions about Hutchings’ departure.

“[D]ue to this commitment to providing a safe, fair and respectful work environment,” Holmes responded, “we are not going to grant your interview requests on the subject of your email.”

Multiple complaints

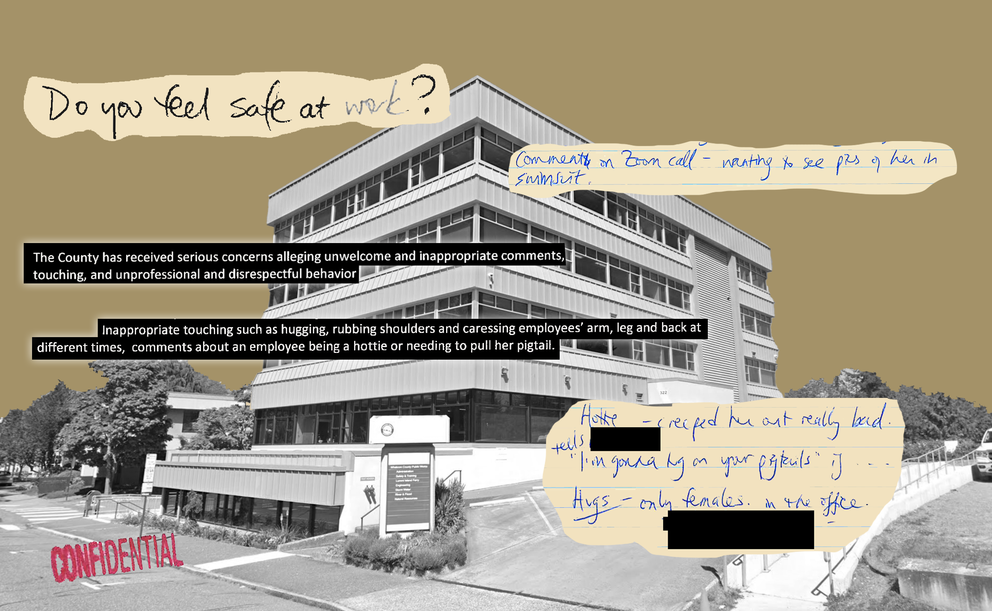

Internal records reveal that three different women reported Hutchings for repeatedly hugging them without their consent, touching a female employee’s thigh and asking a high-ranking manager to see pictures of her in a swimsuit.

One female employee, who we will call “Wendy,” first reported her discomfort with Hutchings in the fall of 2021. (Cascade PBS has granted the woman's request for anonymity to protect her privacy as a victim of alleged sexual harassment.)

The county’s initial response to her complaint was to organize a “facilitated counseling session” with her, Hutchings and a “coach.” Records show no further follow-up for nearly a year after her initial complaint, with HR re-engaging only after a second employee came forward to report inappropriate comments and touching.

Text messages Wendy submitted to HR show Hutchings frequently contacted her on nights and weekends about personal topics, sharing family frustrations, inviting her on walks, commenting on her body and in one case telling her that he “like[s] feeling like the one who can take care of you.”

Wendy was hesitant to bring her concerns to HR after reporting her previous boss for harassment in 2014, according to a letter her lawyer sent to the county. Notes from a manager who interviewed Wendy noted she was “very skeptical” of HR due to how the previous complaint was handled and “will not be interviewed in a group setting with HR again.”

Find tools and resources in Cascade PBS’s Check Your Work guide to search workplace safety records and complaints for businesses in your community.

Internal records show Wendy told HR she had known Hutchings for 15 years and largely enjoyed working with him until 2020, when he began focusing unwelcome attention on her.

Hutchings called her nicknames like “sweetie,” “sunshine,” “baby” and “momma.” He would hug her without asking, sometimes from behind, often enough that she put up a “no hugs” sign at her desk.

Wendy provided screenshots of 120 texts out of more than 200 she said Hutchings sent her over two years. A sample of texts circulated to senior county HR officials reveal largely one-sided conversations in which Hutchings expresses anguish over his family, seeks emotional support, offers to bring her flowers and fresh eggs, and invites her to watch the moonrise. After inviting her for a walk on a Saturday, he adds, “This is not a date!”

“Just home from sailing,” Hutchings texted one Saturday at 6:52 p.m. “Starting fire, listening to Jack Johnson. What you doing?”

In an email to Cascade PBS relayed through her lawyer, Wendy wrote that she tried at first to be patient with Hutchings, but eventually he “took it way too far.”

“My family would question me whenever they would visit or I would visit them,” she wrote, “why does your boss text you all the time at all hours?”

She first reported Hutchings’ behavior to then-Assistant Director Elizabeth Kosa in September 2021, according to HR records. She also confronted Hutchings that same day, according to a log she provided to HR.

About one week later, Kosa organized a “facilitated counseling session” with Hutchings, Wendy and a person HR later referred to as a “coach.” Wendy was “very clear in telling Mr. Hutchings to stop communicating with her after hours [and] about his personal life,” according to Kosa’s account in a third-party investigation report.

After the meeting, Hutchings began to treat Wendy differently at work, she told the investigator. He excluded her from important work and undermined her in front of colleagues, in one case criticizing her for wearing flip-flops. Three days after inviting her to the non-date walk, he yelled at her during a work meeting, saying “I’m done with you. I’m not talking to you anymore,” according to a log she submitted to HR. He then apologized and scheduled a meeting to discuss his feelings about her.

County email records appear to indicate that for nearly a full year following Wendy’s complaint, leadership took no further investigative or disciplinary action.

Then in early September 2022, as Hutchings cleaned out COVID-19 supplies from an operations office alongside a female worker, he held a thermometer up to her forehead to take her temperature and said, “You’re a hottie,” according to HR records. The worker later recalled to an investigator that Hutchings had put his hand on her thigh during a leadership training in 2016 or 2017.

The county brought in a third-party investigator to interview Wendy and the operations worker in late October 2022. The investigative report echoed what the female employees told Kosa and later HR. It also revealed Hutchings had allegedly told a third female colleague he would “need to see a photo of her underwater, in her swimsuit” after she shared plans for diving.

But unbeknownst to the women, Hutchings had already emailed Schroeder, the deputy executive, saying he would resign. Before the investigative report was delivered, Hutchings and senior county leaders had largely hammered out an agreement that would allow him to characterize his departure as a resignation and required the county to omit information about his misconduct when contacted by future employers.

By the time the investigative report came back, the county had already started drafting Hutchings a letter of recommendation. The investigator did not interview Hutchings.

‘Going on a long time’

Meeting minutes show the Lynden City Council confirmed Hutchings as their Public Works director on May 15, 2023.

Mayor Korthuis did not respond to inquiries about Hutchings. It remains unclear how much the city of Lynden knew about Hutchings’ behavior when they hired him.

“It sickens and infuriates me how much he was not held accountable for his actions and how much he was protected,” Wendy wrote in an email. “In my opinion they clearly went out of their way on that agreement to hide everything, and to protect the abuser at the expense of the victim.”

Wendy noted that Whatcom County has updated its sexual harassment trainings since Hutchings’ departure and updated policies to require full investigations of all complaints, but said she needed years of therapy to deal with the “daily toll” of the abuse. The nonstop messages exhausted her physically and mentally, she wrote, to the point that she developed severe stomach pain leading to multiple emergency room trips.

Wendy’s attorney sent a letter to the county on Oct. 24, 2023, accusing the county of violating federal and state laws against discrimination based on sex and retaliation against those who report it.

“It seems in this case that the county actually supported [Wendy’s] abuser,” the attorney wrote, “and certainly failed to take prompt and effective action to stop the discrimination.”

The letter alleges that despite agreeing not to contact her, Hutchings in April 2023 left a note in her mailbox that indicated an interest in re-engaging in a relationship with her. He also included a gift: a book on personal boundaries. Hutchings’ separation agreement with Whatcom County references a recent no-contact directive, although it does not say with whom.

The letter sought $400,000 and “prospective anti-sex discrimination corrective action as negotiated.” A settlement agreement shows the county ultimately paid $225,000.

Wendy had kept a log of her interactions with Hutchings, which she later submitted to HR. An HR representative annotated Wendy’s log in pencil, circling the date when Wendy first confronted Hutchings.

“I told him I was uncomfortable with his level of engaging me outside of work in personal matters (texting etc.) and that it was bordering on becoming super inappropriate,” Wendy wrote in that day’s entry.

The HR representative underlined the beginning of the next sentence.

“This has been going on a long time.”