As I was gathering all my materials to write a profile of the late TV producer, actor, director, stuntman and community activist Nate Long, I initially struggled to find and hear back from sources. But once word got out that I was writing about the Nate Long, I received a wealth of calls from former students and collaborators — many who worked with him decades ago — who were eager to share their memories.

I almost couldn’t keep up with the rush of insights.

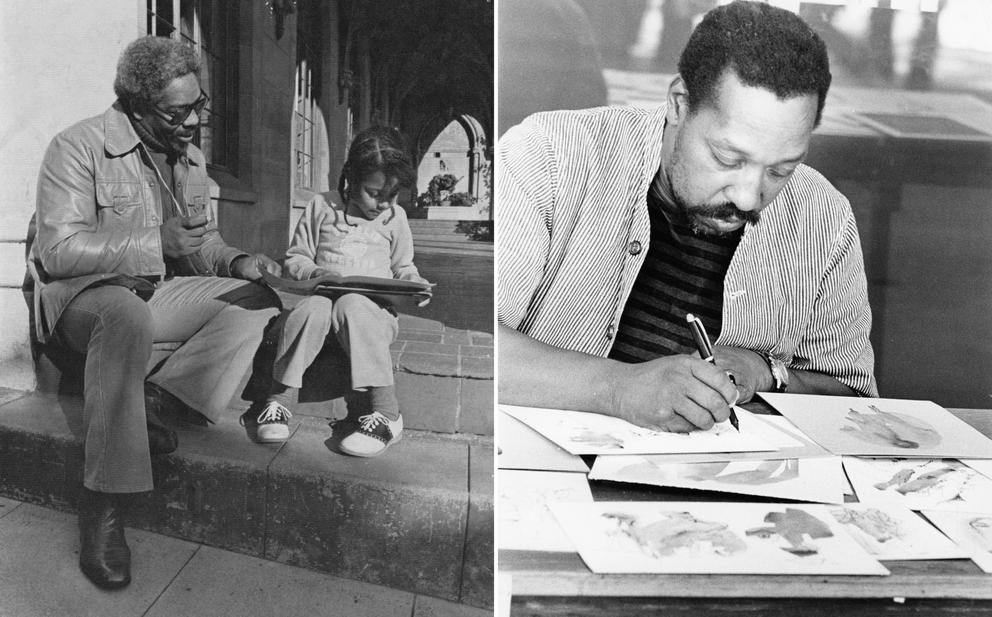

As I describe in my profile, Long was a giant in the Central District community and the Seattle film scene from the 1960s through the 1990s, teaching young adults the basics of film production and overseeing Action Inner City, a TV public affairs program by and for Black teens. Many of his mentees went on to illustrious careers in Seattle, including Norm Rice as mayor, Steve Pool as a beloved KOMO meteorologist and arts advocate Vivian Phillips.

Kibibi Monié, singer and founder of Nu Black Arts West Theatre, learned to edit film from Long in the 1970s, and recalled that he was “instrumental to keeping the African American community connected.” Actor T. Dennard — an extra in Long’s TV series South by Northwest, about Black pioneers in the PNW — remembered him as a man who “really cared about art and Black artists in Seattle.” (You can find eight episodes of South by Northwest on YouTube.)

And while writing this piece, I learned that even my life had been touched by Long. One of my favorite movies of all time, Scorchy, a pulpy Seattle-set 1976 crime film starring Connie Stevens, features Long in a bit role as a slickly dressed cop. What couldn’t Long do?

While it was impossible to include every quote I captured, the volume of connections demonstrated the breadth of Long’s impact on Seattle’s Black community all these decades later. The commentary not only fleshed out a portrait of Long, but also reminded me why Black Arts Legacies is so crucial: It’s a mosaic of stories, memories, photos and videos shaped by the people influenced by the featured artists.

I had a similar thought pop up while researching the life and work of the first Black art instructor in Washington, the now little-known Seattle painter and musician Milt Simons.

I was completely bowled over the first time I saw his paintings, which he made from the mid-1940s to his untimely death at age 50 in 1973. His use of color and abstracted figures seemed ahead of its mid-century era. There was a liquid emotion in the way Simons blended his greens, yellows, pinks and milky grays.

My sense of awe only grew after listening to musical recordings, via the University of Washington Ethnomusicology Department’s Soundcloud, by Simons and collaborator Paul Dusenbury’s classical/Indian raga/American jazz-fusion band, Jasis, aka Jazz-Art Spontaneous Improvisational Synthesis.

With Simons on the vibraphone, Jasis’ sound is out of this world — woozy yet structured, bubbly and kind of abrasive, something I could easily imagine hearing at a rave afterparty. According to Simons’ cousin Linda Holden Givens, the rare, out-of-print EP is highly coveted by record collectors around the globe.

While researching Simons, I found myself coming back to one thought: How could someone like Milt have gone under the radar this long? As I explained in my profile, Simons’ obscurity is partially because he had no formal representation and was not significantly collected by museums.

Chalk this up to his being Black, not to mention to his edgy and experimental art interests. Simons’ biggest advocate — his widow, artist Marianne Hanson — passed away in 2015, leaving very few living people who remember and are familiar with Simons’ story and work.

His story underscored for me the other major reason Black Arts Legacies is so important: to highlight and celebrate histories and figures in Seattle that have been actively obscured or have faded into the past. By amplifying Simons’ lifetime of pushing boundaries and provoking thought, I hope his work gets the recognition and critical acclaim he so rightly deserved.

Get more Black Arts Legacies

This newsletter features a new artist each week, along with additional stories, exclusive content and responses to reader questions.