Community and government officials have long known about the region’s natural assets, such as the 1.5 million-acre Colville National Forest, for outdoor recreation. But many saw the beautiful landscape mostly as a way to attract new businesses and workers to the region.

Then more visitors started showing up at the region’s trailheads, waterways and campgrounds during the pandemic.

This story is part of a Crosscut focus on tourism, Open for Visitors

“All of a sudden, we have all these new people camping, recreating and hiking,” said Shelly Stevens, who oversees regional marketing efforts for the Tri County Economic Development District, which aims to develop business growth in the three counties.

That made the region a prime candidate for the State of Washington Tourism’s new Rural Tourism Support program. The nonprofit tasked with running the state tourism program had prioritized rural destination development in its tourism strategy.

Over the past several months, community and business leaders worked with the organization to develop a strategic plan to help the area develop as a destination and get the word out to potential visitors.

But for Stevens, it was also important to build its tourism sector in a way that didn’t impact residents’ quality of life.

“If you look at other really popular tourist destinations that cater to outdoor recreation [visitors], many of them have been loved to death. It’s been changed; then the economy changes in a way these communities haven’t anticipated,” she said. “We saw this strategic planning process as a way to get ahead of that.”

More than marketing

While many think of marketing when state tourism programs come to mind, organizations can’t neglect other tasks, such as destination development and management, said David Blandford, executive director for State of Washington Tourism.

Some areas of the state — Seattle, for example — are well-established destinations known by visitors. Many rural areas have attractions, such as hiking trails or winery tasting rooms, that could draw visitors. But they generally don’t have the financial or other support to fully develop a strategy to attract visitors and sustain an industry that provides dollars to local businesses and fills municipal tax coffers.

The Rural Tourism Support program provides a structure for rural communities to develop a long-term strategy, Blandford said.

The Tri County Economic Development District and the northeast Washington area are the first participants in the program. The program will head to north-central Washington this fall — State of Washington Tourism has announced that it will work with the North Central Washington Economic Development District on a tourism strategy for the region, which includes Chelan, Douglas and Okanogan counties and the Colville Confederated Tribes.

The tri-county region in northeast Washington still doesn’t have a designated agency for tourism. Stevens and the Tri County Economic Development District have focused primarily on developing promotional graphics and educational YouTube videos in-house, she said.

Public meetings where community members could provide feedback on building the region’s tourism sector have been part of the process. The sessions, facilitated by sustainable-tourism expert Kristin Dahl, focused on marketing and branding, outdoor recreation and turning a good destination into a great one.

Stevens found value in holding meetings that included a broad section of the community, including government officials, business officials, residents and tribal representatives. Representatives from the region’s Indigenous communities also participated.

Stevens said it’s a priority to partner with the tribes to ensure that tourism efforts respectfully integrate Indigenous communities' history and culture and their separate tourism development efforts. “We need people to be respectful and sensitive about their culture and heritage,” she said.

The Kalispel Tribe of Indians sent two representatives, one to address the economic impacts and one to address a natural-resource perspective.

The tribe is located inside Pend Oreille County, which is 65% public land and has a population of about 14,000 residents. It was important to address the importance of factoring in the preservation of wildlife and public lands when crafting a tourism strategy, said Mike Lithgow, policy analyst for the tribe’s natural resources department.

“There is a balance to be struck there,” he said.

In addition, there is a deep tribal history and culture behind many of those lands that could be shared with visitors, he said. He believes integrating those aspects — through tools such as signage or guides — could further provide visitors with a better sense of place. And that inclusion “makes people who live here feel more comfortable with this new influx of tourism activity,” he said.

By the end of the process, the organization and the community came up with different projects to focus on in the coming months and years. They included improving its online presence to provide information to prospective visitors, supporting entrepreneurs interested in developing businesses to serve visitors and training residents in the region as part of an ambassador program. The organization will be eligible to apply for grants from State of Washington Tourism to help pay for these efforts.

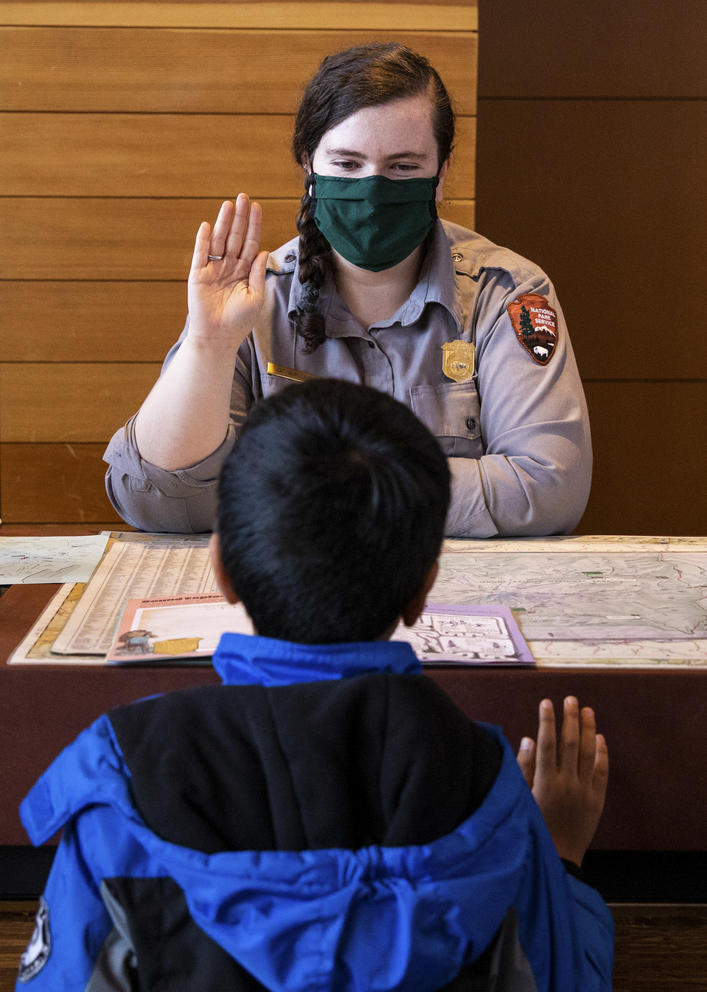

These ambassadors will guide visitors not only on what to do at the destination, but also on things that might not occur to visitors, such as the various roadways in the rural area or how to ensure there is no trace of a visitor, such as trash, in a campsite or hiking trail.

Stevens of the Tri County Economic Development District wants to build on the organization’s efforts to push for responsible recreation, including a series of animated how-to videos created during the pandemic.

“That kind of education is going to be important,” she said.

Sustainable tourism

Indeed, promoting “responsible” or “sustainable” tourism is not just a crucial part of rural destination development; it’s at the center of the state’s new tourism brand.

While state tourism officials want to invite new and repeat visitors to immerse themselves in all that the state has to offer, the messaging will emphasize the importance of being respectful to the communities they’re visiting and to adopt good practices, such as proper waste disposal while camping or hiking, Blandford said.

Many tourism officials are now looking at a triple bottom line: profit, people and planet, said Dipra Jha, assistant director of the School of Hospitality Business Management at Washington State University and a board member for State of Washington Tourism.

Jha said the pandemic halt to most travel provided popular destinations around the world with a moment to evaluate the adverse effects of “over-tourism”: when visitors overtake the destination’s environment and negatively impact residents' quality of life.

Washington can try to ensure that doesn’t happen here by adopting different strategies, including encouraging travel to less-visited locations that provide an experience similar to popular destinations and education on how to take care of the destination and its people, Jha said.

For example, the Snoqualmie Tribal Ancestral Lands Movement in western Washington aims to tell about the tribe’s connection to the land and different recreational best practices, such as staying on the trail and picking up trash.

“We’re educating the visitor to come here and have a great time, but to make sure [they’re] doing it responsibly and ethically and they’re leaving the place better than they found it,” he said.

Get the latest in election news

In the weeks leading up to each election (and occasionally during the legislative session), Crosscut's Election newsletter will provide you with everything you need to know about races, candidates and policy in WA state.