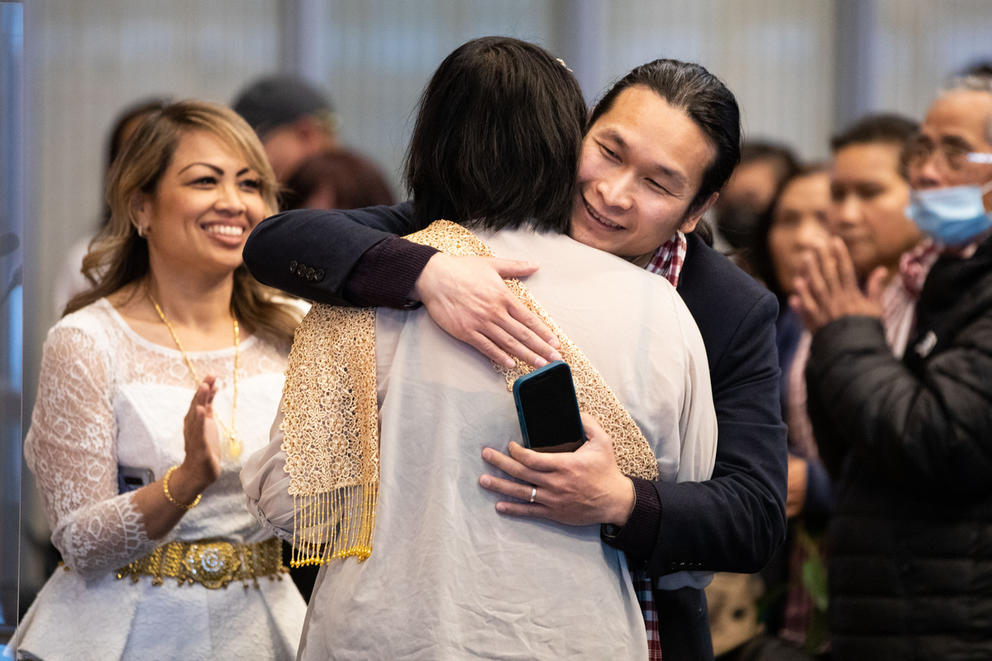

Mell was born in a refugee camp in Thailand after his family was forced to flee Cambodia amid a genocide that began 48 years ago on April 17. This year, Mell called on the city to recognize that anniversary in a proclamation, which he and dozens of other Khmer community members accepted at City Hall on Tuesday.

“The biggest thing is – again – is visibility,” Mell said. “To recognize that there is a body, a population of residents here that have gone through a lot.”

The Khmer Rouge, a communist regime, captured Cambodia’s capital in 1975, sparking a yearslong genocide that ended in 1979 and left at least 1.7 million dead. The U.S. accepted hundreds of thousands of refugees, some of whom landed in Seattle, which has one of the largest Cambodian American populations in the country. Mell wants to see more visibility for his community and a deeper sense of pride among younger generations of Khmer Americans living here.

One of those young community members was happy to see some familiar faces – many of whom she hadn’t seen since before the pandemic – at Tuesday’s event. Ammara Touch, 24, echoed Mell’s concerns about the community’s lack of visibility.

“People don’t really even know, like, who Khmer people or Cambodian people are,” she said.

Being invisible

Mell’s family had planned to relocate to Australia, but his father died while Mell was still a young child. His mother redirected the family to the U.S. instead.

“Our community is very small, so we tend to run in similar circles … People are connected in different ways.” Mell said. “My mom, you know, knows other people from the [refugee] camps.”

Mell’s story, like that of many Khmer Americans, is characterized by hardship that is largely unknown in this country.

“When we talk about, like, Asian American history, you know, we barely get mentioned,” said Mell, who considers himself part of the “1.5 generation.” “Even thinking back to my middle school years … We basically read, like, a paragraph of the Khmer Rouge genocide.”

Bill Oung left Cambodia before Phnom Penh fell because of his father’s work as a diplomat, which led the family to Indonesia. Oung, 67, remembers being in Washington, D.C., when he heard about the evacuation of the U.S. Embassy in Cambodia.

“You have no place to go back,” said Oung, who lives in Everett. “I just couldn’t speak.”

He has dedicated energy to supporting his community through the years, including through organizations he co-founded like the Cambodian American Community Council of Washington and the Seattle-Sihanoukville Sister City Association.

This work is especially impactful in places like Seattle, which has a Cambodian American population of 18,000, the third largest in the U.S. behind Los Angeles and Boston, according to 2019 data from the Pew Research Center.

“Sometimes people ask [the] Council, ‘Why do you work on proclamations that are international in scope?’” Seattle Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda, whom Mell approached for this year’s proclamation, said in an interview with Crosscut. “I think it’s really important to remind folks that this has a direct impact on our community residents.”

The city previously recognized the Cambodian genocide through proclamations in 2015 and 2017, and Tacoma declared a Cambodian Genocide Remembrance Week in April 2022.

“This is not ancient history,” Mosqueda said. “It’s important for folks to have historical knowledge about community members, but also to really lift up the resiliency and the power and strength of that community.”

Forging intergenerational connections

Older Cambodian Americans felt the direct impact of the genocide, but younger Khmer Americans want to connect to their history, too.

“It’s very, like, hush-hush,” Touch said. “Nobody wants to talk about it.”

She understands why. While her father shared his experiences with her, she knows other community members may not want to pass their traumatic memories to their children, although, Touch added, this can happen anyway because of intergenerational trauma.

While she wished more young Khmer Americans had shown up to Tuesday’s event at City Hall, she wasn’t the only community member in her age group who attended.

Savannah Son, youth coordinator for the Khmer Advocacy and Advancement Group, also knows how difficult it can be for people to talk about their experiences.

“You want to know your family history,” Son, 26, said after the ceremony. “You have this relationship to this history, but it’s not the same that they do.”