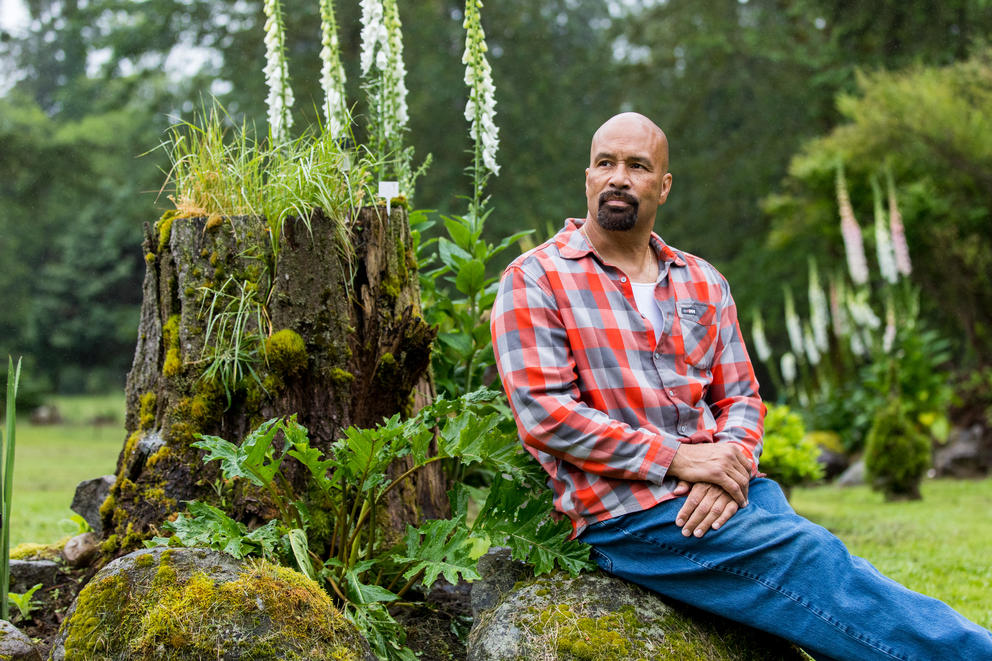

Sanders, a 60-year-old Air Force veteran, was in prison for 27 years for shooting at a police officer during a high-speed chase, a crime he says he’s extremely remorseful for. But now that he’s served his time in prison, Sanders’ fears about the court fines have been realized: The roughly $65,000 the King County court ordered him to pay back in 1995 for the property damage from the chase has ballooned, with interest, to $250,000 today.

This story is part of a series called Justice by Geography from InvestigateWest. The independent news nonprofit is dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Visit invw.org/newsletters to sign up for weekly updates.

Sanders doesn’t know how to rebuild his finances or find a place to live. He’s currently living with his 90-year-old mother in Seattle, and he’s constantly doing mental calculations. How many years of work does he have in him? Can he one day retire? Will he ever pay off this debt?

“How do you pay off a quarter-million debt when you’re unemployed and trying to do everything else — pay probation costs, find a place to live in Seattle, pay insurance and the cost of daily life?” Sanders said. “Imagine all that on top of a quarter-million debt. It’s inconceivable.”

Legal financial obligations, or LFOs, can burden people with suffocating debt long after they’ve done their time in prison. Yet the way court fines and fees are imposed in Washington can depend both on who you are and where the crime occurred. Black, Indigenous and Latino people are given more LFOs at higher rates than Asian or White people, a 2021 Seattle University School of Law study found. Meanwhile, counties and judges vary widely in how they assess and collect legal financial obligations, according to a recent report by the Washington State Supreme Court Minority and Justice Commission. Rural counties may rely more on these fines and fees to subsidize their budget, and some courts may see them as necessary punishment for those convicted of crimes.

Recent state legislation has improved the system, advocates say. In 2018, the state passed a bill that, in part, ensures that courts can’t jail a person for these debts unless they have the means to pay. And this year, a new law passed that gives judges discretion to waive certain court fees while allowing people with LFO debt to get relief from fines and fees if they show they have an inability to pay.

But experts say disparities in court debt by geography and race persist. Alexes Harris, a sociology professor at University of Washington who has spent decades studying monetary sanctions here and elsewhere, said only radical change can make a meaningful difference.

“It’s still variable by county in terms of the amount of fines and fees that you’re going to get, and the consequences for not being able to pay them,” Harris said. “Our system is so full of injustice, both racial and economic, that a system of monetary sanctions based on financial penalties can never be just. In my mind, we just need to abolish it.”

Worth the cost?

The number of court fines and fees doled out in Washington has increased dramatically since the 1980s. That’s mainly for two reasons, said Evan Walker, a policy analyst for the left-leaning Washington State Budget & Policy Center. For one, it was seen by some in the criminal justice system as a rightful punishment for a crime. And two: Counties feel they need the money to make up for a lack of state funding — Washington ranks among the bottom in the country in state funding for trial courts, federal statistics show.

“The increased need for making up government revenue since the ’70s and ’80s has really influenced why agencies have gotten to this point,” Walker said.

Research backs this up. Earlier this year, a report from the Washington State Supreme Court Minority and Justice Commission studied the state’s system of legal financial obligations. Paid for with a federal grant, the study found that the state’s “particularly challenging court funding scheme” produces “vast disparities among counties, cities, and even judges in how court fees are imposed and enforced across the state.”

Some counties impose harsher court fees than others. Historically, those counties have also been politically conservative, said Harris. She found in a 2004 analysis that counties with higher percentages of people voting Republican in the presidential election tended to sentence defendants to higher court fines and fees.

Some court fines and fees in Washington are mandatory for every judge. For each felony or gross misdemeanor conviction in Superior Court, there’s a mandatory $500 “Victim Penalty Assessment.” There’s also a $100 DNA collection fee for many defendants’ first convictions. Courts can also order restitution, meant for convicts who caused injury to a person or damage to property.

These fines and fees can grow rapidly with interest. Washington allows a 12% interest rate on restitution, though recent legislation prohibited that rate on non-restitution. Washington law allows private collection agencies to charge up to 50% on top of the existing debt — more than many other states allow.

And the leniency of a certain judge or jurisdiction can play a major role in how much debt accrues. A research report in 2018 revealed the case of a Latino man in Washington who had his LFO interest deferred until after his 13-year prison sentence. But while in custody, he was charged with an additional felony in Walla Walla, where a judge did not grant him deferred interest.

“He reported that, due to the different approaches of presiding judges, his Walla Walla debt had more than doubled by the time he was released,” the 2017 report by Harris and others states. “He had perceived his King County debt as more manageable and had decided to only make payments toward that LFO.”

Meanwhile, some counties have jailed people for not paying their court debts. Benton County, for example, had a practice of arresting people or forcing manual labor for not paying these debts until 2016, when they settled a class-action lawsuit. Spokane County, too, settled a class-action lawsuit in 2014 accusing it of jailing more than 1,000 people over a six-year period for not paying court fees.

But courts collect only a small fraction of the fines and fees that they give out. From 2014-16, superior courts in Washington imposed $130 million in legal financial obligations, yet collected just $7 million, according to the Minority and Justice Commission report. District and municipal courts imposed $88 million yet collected just $4 million. And many counties add an additional fee just for collecting the court debt in the first place. Clerks said that without the fee, they would have to ease up on their efforts to collect these debts.

“I’m not sure if we could continue our program if we lose the fee entirely,” one clerk reported.

Perpetuating poverty

Not only are court fees imposed unevenly across the state, but they hit those who already are low-income, hampering their ability to rebuild their life after prison.

In 2008, Chanel Rhymes took a plea deal on a theft charge — an Alford plea, in which she maintained her innocence. A Pierce County judge said she owed $26,000 in restitution in addition to her time incarcerated.

Today, Rhymes is the director of advocacy for the Northwest Community Bail Fund, working to reduce or eliminate court fines and fees like those she was given years ago. But her own debt remains a burden. It’s now $102,588 with interest. The debt is constantly hanging over her head and has prevented her from getting her record expunged, blocking her from getting certain jobs or causing her to lose jobs once her employer finds out.

“I can’t move where I want to. I can’t live where I want to. I’ve been stuck in this place I’ve lived for eight years, and I hate it,” Rhymes said. “It just ends up having a ripple effect for the rest of your life.”

In Washington, poorer neighborhoods are most impacted by court debt. Harris and other researchers found that within each county in Washington, low-income neighborhoods carry the most LFO debt per capita. The researchers dubbed these neighborhoods “debtors’ blocks.” They are more populated by people of color.

While the study didn’t examine whether court debts directly cause poverty in these communities, it did find that the two are linked: Neighborhoods with high per capita LFO debt are associated with increased future poverty rates.

“There’s something about a relationship between LFOs being sentenced at a high rate and certain communities that lead to the exacerbation of poverty,” Harris said.

Rhymes know exactly how that can work. She’s resigned herself to the idea that she’ll never pay her debt, and the felony conviction will be on her record, decades after the crime occurred and long after her prison sentence.

Rhymes likens courts’ efforts to collect these payments to squeezing “blood from a stone.” She sees these debts as arbitrary — numbers on a computer that serve to hold people down.

“You can’t fund our society on the backs of the poorest people,” Rhymes said. “That makes no sense.”

Reforming the system

Rep. Tarra Simmons, D-Bremerton, has long made reforming the LFO system her mission. She had her own fines and fees from a prison sentence years ago. Since then, she’s become the founding director of Civil Survival, a nonprofit that helps former prisoners engage in advocacy, and in 2021, she became the first formerly incarcerated person to win a state election in Washington.

This year, she sponsored House Bill 1412, which passed and gives judges discretion to waive certain previously imposed court fees if defendants can demonstrate that they don’t have the current or “likely future ability to pay.”

“I think that the overwhelming majority of my colleagues are starting to see the traps that LFOs put people in,” Simmons said. “We are spending dollars to chase dimes.”

Simmons and reform advocates are focusing on courts’ mandatory fees. Specifically, they want to eliminate the Victim Penalty Assessment and the DNA collection fee — a total of $600 between them per case. That change was originally part of Simmons’ HB 1412 and was taken out at the last minute, but Simmons argues it should be an easy fix. It would cost $4 million in state funding to replace what counties lose without the Victim Penalty Assessment.

Currently, those funds are typically used by prosecutor’s offices to fund victim advocates and work with witnesses to facilitate testimony, said Hannah Woerner, an attorney with Columbia Legal Services, a legal aid group.

“It’s a blanket fee that’s being assessed on folks who move through the criminal legal system that we’re using to pay for necessary services within prosecutor’s offices,” Woerner said. “But in a way, that serves to perpetuate the injustice within the LFO system.”

Still, removing those mandatory fees and making them discretionary brings its own concerns.

“It [would be] progress,” Simmons said. “But I am concerned about justice by geography whenever you give judges discretion.”

That kind of discretion creates uneven distribution of justice across the state, Harris argues. In order to eliminate that, she said the state law on monetary sanctions needs to leave no wiggle room on the criteria judges consider when determining if someone has the ability to pay their court debts. That would mean only considering a defendant’s current ability to pay, not their “likely future ability,” as the law says now.

Ultimately, however, advocates for LFO reform question the existence of these fines and fees at all. If courts need more money in the system, it shouldn’t come from those who are already being punished, Harris said. It’s an idea gaining some traction nationally. In 2020, California ended the collection of dozens of court-related fees, canceling an estimated $16 billion in outstanding debt.

“We need to figure out our priorities. Are they redemption and re-entering people into society so they can be productive?” Harris asks.

In a way, after having served 27 years in a Washington prison, Nathaniel Sanders is thankful for the harsh sentence he received. He makes no excuses for what happened. In fact, he said the officer whom Sanders shot at back in 1995, when Sanders was struggling with drug addiction, “saved my life,” and got him off the streets.

“I used it as a catalyst for a complete transformation,” Sanders said.

Today, Sanders said he’s involved with his church and as many nonprofit organizations as he can be. He hopes to get a job driving big rigs and building retirement. But when he sees how much his debt has grown since 1995, he’s overwhelmed. If it were just the original $65,000, that’s one thing. He calls it “insanity” that he’s being asked to pay a quarter million dollars, even after he made payments from prison all these years.

If not for his family, church and community support, Sanders has a guess as to where he might be: back to drugs.

“If I didn’t have that support, and I had something like that hanging over my head, I guarantee you I’d go back into that life. Because there’s no other way to get this off you,” Sanders said. “With something like that hanging over your head, it will never be over.”

InvestigateWest (invw.org) is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Visit invw.org/newsletters to sign up for weekly updates.