“We have a moral obligation, the governor would argue, to support these communities and help them repair,” said RaShelle Davis, a senior policy adviser in Inslee’s office.

The fund parallels recommendations from the Social Equity in Cannabis Task Force, which advises the Legislature and governor on policies that even the playing field in the weed industry. The move parallels a nationwide push among state governments, including New York and Illinois, to confront the legacy of the war on drugs 一 which saw the criminalization of people of color, particularly Black Americans, for drug-related offenses. Advocates consider the reinvestment fund a good start to remedying inequities, but believe more can be done.

Jim Buchanan, president of the Washington State African American Cannabis Association, initially wanted to see an annual $250 million allocation to the reinvestment fund, which would shake out to about half of the state’s projected cannabis tax revenue. When the governor announced the funding would be halved, Buchanan felt it was better than nothing.

He said, “$125 million is $125 million a year more than what we had before."

How it works

Reinvesting in Washington’s communities would involve drawing funds from the state’s dedicated marijuana account, which holds money from cannabis excise taxes, penalties, license fees and forfeitures.

The projected cannabis revenue for Washington’s 2021 to 2023 budget cycle surpassed the billion-dollar mark. More than half of this was slated for health care, while about a third went to the state general fund. Other sectors benefiting from the revenue included local governments; licensing and enforcement; education and prevention; and research and testing.

“Now that there’s billions of dollars coming into states that is generated by the legalization of cannabis, we have a responsibility to help repair those communities that were overpoliced, that experienced disproportionate rates of violence,” Davis said.

The $125 million for the reinvestment fund would focus on four key areas: preventing violence; implementing reentry services for those who were formerly incarcerated; giving legal aid to expunge records and vacate convictions; and developing economic capital, such as helping first-time homeowners buy their homes and small business owners access loans.

The state plans to develop a study that determines how grants could be targeted to communities. Until then, the state Department of Commerce is prepared to dole out the money through existing programs.

“We didn’t want the department to be having to sit on this money until the study was done and then the plan was done,” said Sheri Sawyer, a senior policy adviser in Inslee’s office.

Until the study wraps up, Davis said Washington will look to its Disproportionately Impacted Areas to identify communities for reinvestment. This refers to a census tract or comparable area with specific characteristics, including high rates of poverty, unemployment and cannabis-related arrests, convictions or incarcerations.

Davis noted the money would be available across the state.

“But the funding would just be for communities that had a disproportionate impact because of the war on drugs,” she said.

Confronting inequities in cannabis

Racial disparities have already put Washington’s cannabis industry under the microscope.

Retailers got their businesses off the ground after the state legalized weed in 2012. Some Black entrepreneurs, however, found themselves unable to profit off of cannabis as disparate enforcement of drug laws in their communities: From 2013 to 2019, for example, Black people in Seattle faced disproportionate citations for cannabis-related offenses compared with the city’s white population.

Washington has worked to remedy the inequities in its cannabis system by, for instance, easing rules in 2021 to make the industry more accessible to those with criminal records. Legislators also approved a program in 2020 to redistribute nearly 40 unused cannabis retail licenses to applicants from communities that faced disproportionate enforcement of cannabis laws.

The state’s plan to reallocate cannabis revenue to communities afflicted by the war on drugs mirrors initiatives Buchanan had noticed outside of Washington.

“I saw what New York did,” he said. “And I just hung on like a pit bull.”

New York state legalized recreational cannabis in 2021, setting aside 40% of its cannabis tax revenue for equity initiatives. The state would, for example, automatically expunge records of those convicted of cannabis offenses no longer considered criminal and allow those with prior convictions to take part in the new market.

It’s a start

The Washington reinvestment account comes at a time when the country is reckoning with its own history of racism and inequitable treatment of Black Americans. Some view this project as a necessary step, but not the only one required.

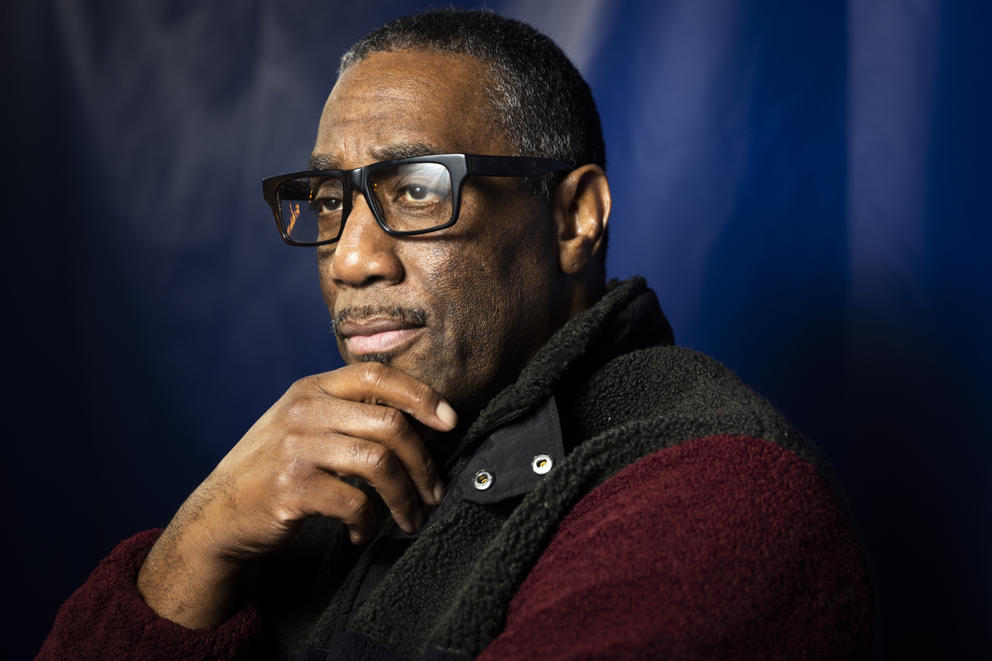

“That $125 million is a down payment,” Elmer Dixon said. “It’s a small down payment on what the government owes our community.”

The money is a minor form of reparations for Dixon, who co-founded Seattle’s Black Panther Party in 1968. He feels much more needs to be done to atone for what he described as a “long history of racist, brutal action” against communities of color.

“It’s a drop in the bucket,” said Dixon, who believes Black and brown people, as well as Native Americans, are owed billions of dollars. ”But you gotta start somewhere.”

The treasurer of the Seattle King County NAACP chapter echoed that sentiment. Darrell Powell, who also serves as one of the vice presidents of the NAACP state-area conference covering Alaska, Oregon and Washington, said he could die on a sword for more money or, alternatively, view this as a start. He said he relayed to Inslee that the areas where the $125 million will go are a billion dollars’ worth of issues.

“I don’t have any expectation that you’re going to solve the ills of the African American and the BIPOC communities on $125 million a year,” he said. “We’re still pushing the envelope to say thank you, if you will, but it’s not enough. And it’s the beginning. And it should have been happening all along.”

Davis of Inslee’s office knows the allocation might feel modest to those who pushed for more money for the community reinvestment fund.

“We recognize that it’s not meeting the community 100%,” Davis said. “But we’re wanting to start somewhere and we made a meaningful investment by doing $125 million.”

Dialogue about repairing the harm done toward Black Americans over the centuries has come up in educational environments, among state governments and even at the national level, when a bill to study slavery reparations emerged in the Legislature in 2021. Some estimate the cost of reparations for Americans whose ancestors were slaves could reach into the trillions.

Sawyer, one of the senior policy advisers in Inslee’s office, said most of the feedback on the community reinvestment fund from her perspective has been generally positive. Still, she understands why some feel skeptical about the size of the allocation when Washington is clocking a billion in cannabis revenue.

“Their perspective, and I can appreciate it, is, ‘We deserve more,’ ” she said. “And it’s not like we disagree with them. We’re just trying to balance this priority with all the other myriad priorities that are also really good.”

Legislation in the works

Washington lawmakers are moving bills forward for the community reinvestment fund, with some modifications.

State Sen. Rebecca Saldana, D-Seattle, and state Rep. Melanie Morgan, D-Parkland, who both serve on the Social Equity in Cannabis Task Force, sponsored companion bills, House Bill 1827 and Senate Bill 5706, that align with the governor’s request for legislation. Saldana also sponsored a separate bill that restructures the allocation.

The legislation, SB 5796, tethers dollar amounts to specific objectives 一 like cannabis pesticide testing, money for local governments and the administration of the Washington State Healthy Youth Survey. The bill also reserves money for areas, including a Community Reinvestment Account, that are not bound by specific dollar amounts.

The idea is that as more money pours in, more goes toward areas not limited by fixed allocations, including reinvestment.

“I think it’s very clear from the community perspective, $125 million is not sufficient,” Saldana said. “The need is much greater.”

Sen. Ann Rivers, R-La Center, broke from other Republicans when she voted in favor of the restructuring bill.

“This is one thing that takes us back to the root of what the people voted for when they approved Initiative 502,” she said, referring to the legalization of recreational cannabis in 2012.

The senator, who has worked on cannabis legislation in the past, was the only Republican on the Labor, Commerce and Tribal Affairs Committee to vote yes on SB 5796.

“There’s still a lot of hesitancy on my side of the aisle about cannabis, about the whole legalization,” she said, but noted people may feel differently when it comes to voting on the floor. “Committee votes can give you a bellwether but are not necessarily the final word.”

On SB 5706, the bill to create the community reinvestment fund, Rivers referred it without recommendation. She said this was a way to avoid delivering a deathblow to the bill.

“When I vote without rec, it means I don’t know, I have a question I need to get answered before I commit one way or the other,” she said.