Now, with the possibility of returning to the classroom for in-person teaching, Vilchez can’t help the anxiety she feels when she thinks of seeing her third grade students in their seats again. In such a small room, she’s not sure how safe she can make the space for herself and for the children.

“How much time am I going to spend cleaning and how much time am I going to spend teaching?” she said. “Did I sign up to become a doctor?”

Like many teachers, Vilchez has felt like more than an educator in recent weeks. All these new responsibilities, much more than her usual teaching would require, have kept her busy since the pandemic hit Washington in the spring. She’s started tracking recent health data, keeping herself up to date on coronavirus news. She has also caught up quickly on efforts to connect kids with meals and technology because at her North Thurston District school, Lydia Hawk Elementary, 70% of students qualify for free or reduced-cost lunches.

Vilchez said many teachers like herself, fueled by all these concerns, have taken up this extra work: “It’s just hard for us to say no.”

More than anything, she wants to see her students in person again. That’s where her teaching is most effective. But she doesn’t know when, or even how, that will be possible.

The final weeks of the previous academic year coincided with pandemic tumult. Now, many Americans are wondering what’s next for schools. President Donald Trump is pushing for nationwide school reopenings, while families and educators express a variety of concerns.

President Donald Trump listens during a "National Dialogue on Safely Reopening America's Schools" event in the East Room of the White House, July 7, 2020. The president has stated that schools, under threat of budget cuts, must reopen to on-campus classrooms in the fall, but has offered little to no guidance or support on how to do so and what schools should do to ensure student health and safety. (Alex Brandon/AP)

Most school districts have yet to announce specific plans for the next school year, but some have promised more concrete ideas in August. On June 11, the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction released guidelines for schools that give an idea of what those plans could look like: Schools could opt to continue virtually or create a hybrid plan of in-person and distance learning. If schools are in-person, they’ll likely have to add safety procedures, like regularly screening students for the coronavirus and requiring face masks.

There’s no blanket mandate for what districts should do this fall. But in general, state schools Superintendent Chris Reykdal has prioritized serving as many students as possible face to face, while following health guidelines.

Cindy Rockholt, assistant state superintendent of educator growth and development, said a special emphasis is being placed on bringing students who’ve faced more difficulties with distance learning back first. But with September still weeks away, she said it’s hard to tell what will happen.

“Right now, because we haven’t moved to where we can get rid of the social distancing expectations, we think that there will be some restrictions on most districts in how they’re able to serve students,” she said.

This tension — a desire to teach students in person versus fears of the coronavirus — has plagued teachers and administrators throughout Washington. Larry Delaney, president of the statewide Washington Education Association teachers union, said some educators he’s spoken to don’t see in-person school as an imminent possibility.

“The trend is heading in the wrong direction, and there’s no way to dispute that,” Delaney said. “It just doesn't compute how we can return to normal schooling, or something that more closely resembles normal schooling, this fall.”

Both Delaney, who has been a high school math teacher in Snohomish County for 27 years, and Vilchez, the teacher from North Thurston, contributed to OSPI’s June guidance. But the path of the pandemic in Washington has changed a lot since then. Delaney said the Washington on which they were basing those guidance decisions weeks ago is not the Washington of today.

“I think the feeling has shifted,” he said. “Six weeks ago, the trend was that [COVID-19] cases were on the way down, but in the last six weeks, we’ve seen a serious spike in the number of cases.”

Superintendent Michelle Reid led her Northshore School District to be one of the first in the country to suspend in-person schooling last March. While she said the district’s ultimate goal is to reopen as soon as possible, she’s skeptical of it happening quickly.

“The community transmission data of this virus is really an important consideration, and right now it feels like, given that the governor has paused reopening plans until July 28, that the data is going in the wrong direction,” she said. “The data would not indicate that opening school at this time would make a lot of sense.”

While Reid said no district plans for the school year will be made public until August, she sees some inconsistencies that need addressing in coming weeks as the district creates its plan. One example is the governor’s guidance of state public meetings law, which prevents large groups from gathering to hamper spread of the coronavirus and requires that school boards meet remotely.

“There is a certain irony in a requirement for boards to meet remotely while they’re set to approve plans for in-person instruction,” Reid said.

Educators, at least, has had more time to plan since last spring, where trial and error was the norm for many teachers. Sarah Applegate, a teacher-librarian in Wenatchee, said she and others have learned more about making remote learning more effective. It’s especially important now, as Applegate assumes schools may begin to return to normal student academic expectations, including grades and testing. At the end of the past academic year, many schools went easier on students, making it harder for their grades to worsen.

“This next year is going to be different,” she said. “We’re going to have some different levels of expectations, I think — but I don’t know.”

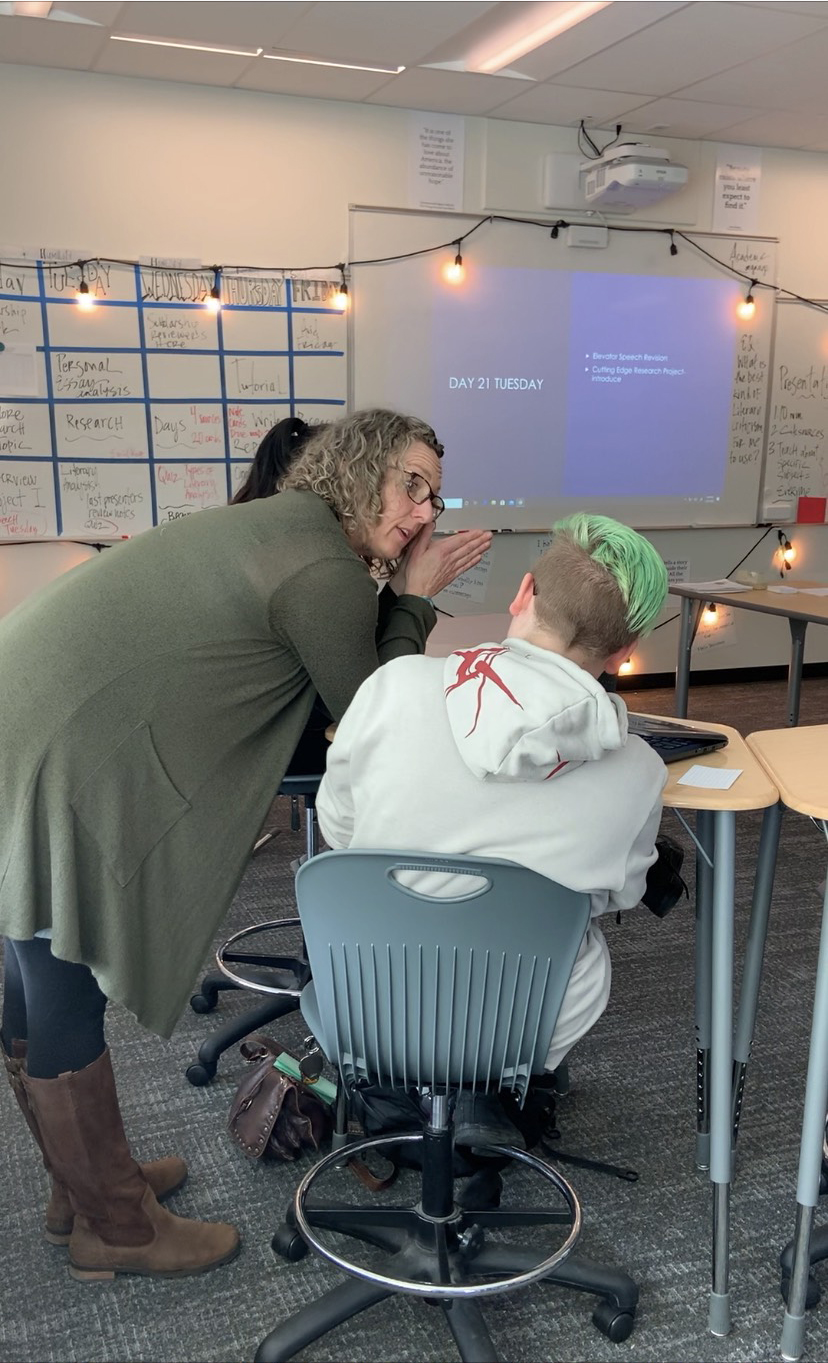

Nasue Nishida, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Strengthening the Teaching Profession in Olympia, said her organization has helped educators navigate online teaching these past few months. That will be the organization’s focus for the foreseeable future, she added. Whatever happens, Nishida thinks it’s unlikely Washington schools will pull back on online learning any time soon.

“Even in a hybrid model, you’re going to have kids doing distance learning at home for a couple days a week,” she said. “At the end of August, I don’t know where we’ll actually be with [reopening]. There’s a lot of energy invested into that and it may or may not happen.”

Delaney hopes districts will put the same effort into developing a potential hybrid learning plan as they will toward continued distance learning plans, since both are a possibility.

“I think that if we are being honest with ourselves as educators, we need to look at the very likely possibility now that we’re going to have to be opening… with some sort of a distanced learning model,” he said.

Kathe Taylor, assistant superintendent of learning and teaching with OSPI, said experience from the past few months has helped planning for schools become more sophisticated. By now, many school districts also have a better sense of which students have struggled the most since schools shut down, such as those with difficulty accessing technology. Knowledge like that is valuable, and makes for more informed future plans.

“We hope not to be in that situation again, where schools are closed and we’re having to deliver online learning or deliver packet-based learning,” she said. “But if we are, it’ll be from a much different vantage point.”