It’s the same routine she has kept since beginning her work 50 years ago to ensure that the Spokane dialect of the Salish language survives her.

“I sit down, and that’s it,” Flett says. “If I think of something, I have to write it down before I forget — I might use it later if I’m not using it now.”

Since she began, Flett has helped establish a Salish curriculum for the tribe’s language school in Wellpinit, Stevens County, and has been the primary author of each edition of the tribe’s Spokane-dialect Salish dictionary. That includes the most recent, published in 2016.

Revitalizing a language is daily work.

“I’m addicted to it,” Flett says. “If you’re meant to do it, that’s what it is. And I feel like I was meant to do this.”

She often uses prayers and songs to help teach the language — she’s currently working on a Spokane dialect version of “Amazing Grace." It’s a good trick for getting other people interested and speaking the language, she says, because it invites them to join in.

“Even just one little prayer, just do that and pretty soon you’ll be adding to it,” she says. If you’re learning a language and see how others speak, “pretty soon you’re doing it, too.”

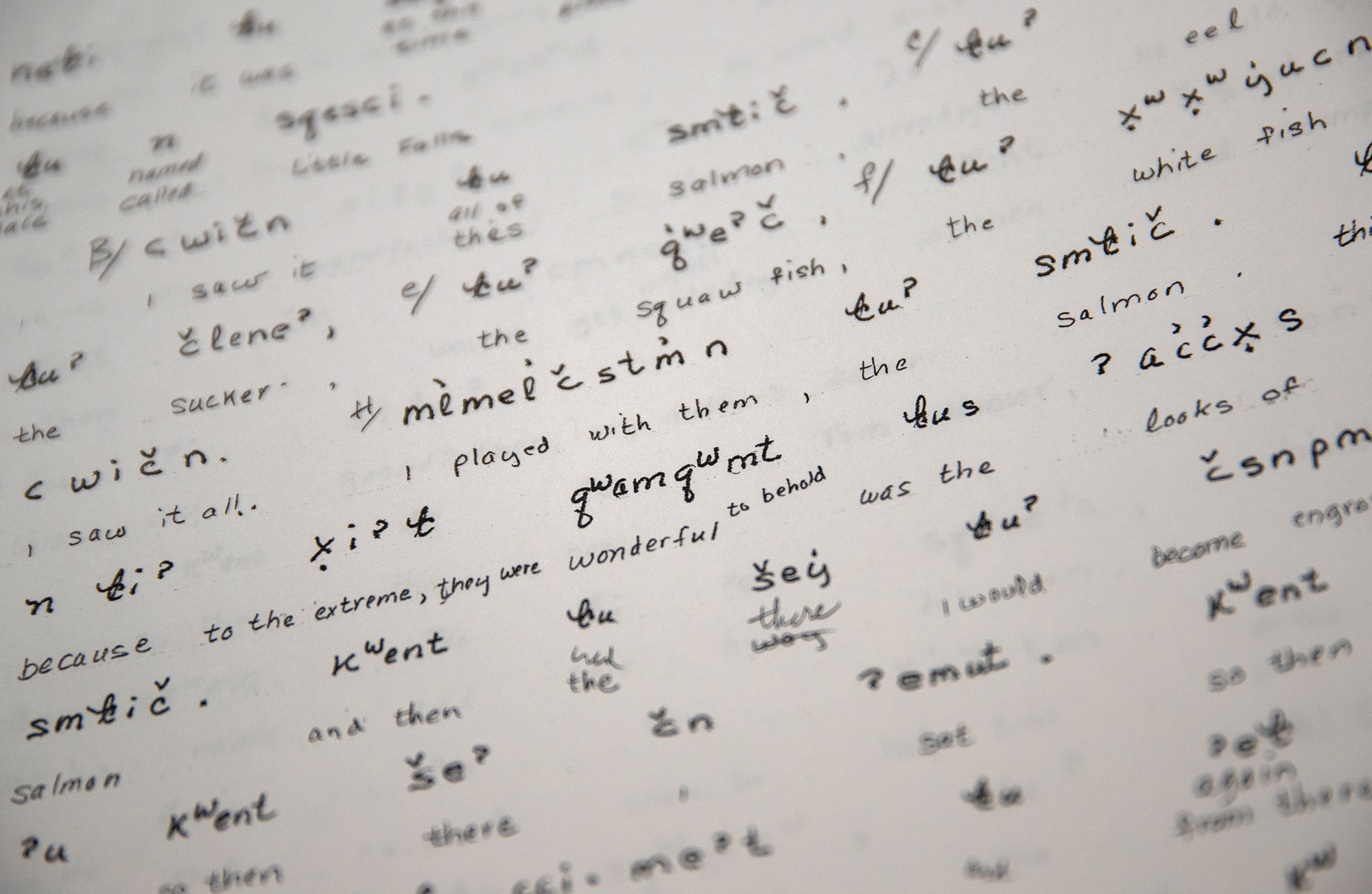

A chunk of Flett's work is dedicated to breaking down words in the language, piece by piece. Marsha Wynecoop, the Spokane Tribe’s language program manager who often helps Flett in her work, describes it like this: In the Spokane language, different parts of a word can describe the word itself.

Wynecoop uses the word for skunk as an example: In its totality, the word means “skunk,” but when you break it down to its various syllables, it also means “something small and bad pretending to be good,” relaying the idea that a skunk is less harmless than it might seem.

“In English, [the word] doesn’t mean anything — it’s more like an object,” she explains. “But in our language, it gives it more of a full meaning of the animal.”

Flett’s process of reviving the Spokane language through careful cataloging and transcription is similar to how other tribes have revived their Native languages. In many cases, elders fluent in their tribe’s tongue have come together to put the language on paper in order to keep it from disappearing.

In the United States, the speaking of Native languages was suppressed and often punished in school systems for decades after Indian boarding schools were first established in 1860. Native people were forced to assimilate to Euro-American culture in a myriad of ways, including speaking English.

By the time the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act allowed Native parents the right to deny their children’s placement in these schools, their language legacy had been damaged nearly irrevocably.

“Everything that we’re doing today would have never happened without the tribal elders who held the language,” Wynecoop says.

Across the state, other tribes have been working diligently on language revival projects, including in public schools, according to Patty Finnegan, bilingual education special projects program supervisor in the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

“Some of them are restoring and preserving language, and some are building educator capacity to use the language in general education classrooms,” she said.

While OSPI doesn’t have a complete list of Native language education programs going on around the state — largely because the state acts as a collaborator or partner in this process and doesn’t track them — a 2018-2019 report says there are about 61,000 Native learners in the state's public schools.

Laura Lynn, program supervisor of the OSPI Office of Native Education, said the tribes govern all aspects of this work.

“If they invite us to be partners in that work, then we do that,” Finnegan adds. “And we’re just beginning to do that work.”

Crafting an Indigenous curriculum

The cornerstone of the state’s partnership with tribes in certifying Native language educators goes back to the First Peoples' Language, Culture and Oral Traditions Renewal bill, which became state law in 2007. The Spokane Tribe's Wynecoop was a core member of the group of tribal language education leaders who first came together to discuss what Native language certification might look like in Washington state.

At the core of the law was the belief that tribes in Washington should control the certification process, because speakers of those languages would know them best. It emphasized tribal sovereignty, ensuring that tribes wouldn’t have to go through the state when certifying Native language teachers and that the tribes would have control over the curriculum they would use. State Sen. John McCoy, a Tulalip tribal citizen and a state House member at the time, pushed for passage of the 2007 bill and said tribal control over the process was especially important for giving tribal elders their due credit.

“When we started this, it was the elders that were the keepers of the language and the history. You’re not going to send 70- or 80-year-old great-grandma to school in order to get a certification to teach a language. You're just not going to do that,” McCoy says. “So it was written that if they had the language, they get the certification, and tribes issue that certification.”

The idea of tribal independence over the teaching of Native languages was fairly new at the time, but now it’s the foundation of the work developing Native language education programs in Washington state.

For Wynecoop and others in the coalition, it was important that tribes have autonomy over how languages were taught — not just so they could craft the rules of certification, but also so that classes could be taught in a way that was more truthful to the heart of Native languages.

“It’s more of an Indigenous model of curriculum,” Wynecoop says, describing the classes taught at the Spokane Tribe’s language school. While some might think to “take English books and transcribe them in the language, that leaves the heart and soul of who we are out of it. That’s just teaching in a Western mindset,” she adds.

Bringing Native languages to future generations

Matt Remle, a member of the Lakota tribe who works with the Marysville School District as its lead Native American liaison, says these programs are still expanding. He has noticed that in many cases school districts incorporating Native language education into their curriculum contain a reservation within their boundaries. This has been helpful in Remle’s case, as he’s helped facilitate Lushootseed language education for the district's Native youth through the Tulalip tribe, whose reservation lies within the school district.

Where that isn’t the case, Remle says, these classes tend to be absent. In Seattle, for example, he has not seen schools that offer permanent Native language classes — although in some cases, students can receive credit for showing competency in a Native language.

But that doesn’t mean these languages aren’t being taught in Seattle. Remle and other language educators are teaching Lushootseed, Lakota and Native sign language on Tuesday nights at North Seattle College for Native learners of all ages. The program is being facilitated by the after-school program Clear Sky Native Youth Council, which is run by the Urban Native Education Alliance. In some ways, Remle prefers this program to formalized classes in a public school. He says that this way, the intricacies of the languages can be more thoroughly explored.

Similar to the Spokane dialect of Salish, Lakota words can often be broken down to reveal deeper meanings within themselves. He uses the word for water, mni, as an example. Once broken down, it can be translated directly into English as “this is giving me life.” This in itself, Remle said, reveals something about the culture that created it.

“It’s like a key to opening up to the worldview that our ancestors had and held, how they viewed the world and their relationship to the greater cosmos,” Remle said. “You can get into that more than you can in a traditional classroom setting.”

Both Wynecoop and Remle weren’t taught the language of their tribe as children, but as educators they can now see their kin grow up in a system where that’s possible.

“Getting them at a younger age is more effective. I can speak from personal experience — I was in my 20s when I started and it was hard,” Remle says.

Watching his kids grow up learning Lakota, he sees that for them it’s intuitive. “They don’t have to do any translating in their heads,” he says. “I’ve just seen how much their minds are like sponges when they’re young.”

Wynecoop says her grandchildren are learning their Native language, and she’s working to ensure that they have that education throughout their time in school. The Spokane Tribe’s language school is in its fourth year, and it hopes to someday have it go from preschool through high school.

As a show of gratitude for Flett's life’s work, the Spokane Tribe is awarding her a lifetime achievement award on Feb. 28 for her part in the progress made since seeding the program within the tribe in 1998.

“She’s been doing it so long she says she doesn’t know how to quit,” Wynecoop said. “She said she wants a paper and pad in her casket.”

For Flett, the work is her life. Preserving it has given her the peace of passing this part of her on and even helped her retain the language.

“I just don’t want it to die,” she says. “It just gets you by the heart.”