A month later, after the girl cycled between hospitals and hotels, her behaviors had “escalated,” social workers noted in the reports they must file each time a child spends a night in a hotel or state office. After at least seven weeks of instability, the 11-year-old was finally placed in a program for troubled foster youth with behaviors that most foster parents find too hard to manage.

This girl is one of a growing number of children that the state has been housing in hotels and state offices — sometimes on and off for weeks or months — as it struggles to rebuild services for a relatively small number of foster youth with significant mental health and behavioral challenges.

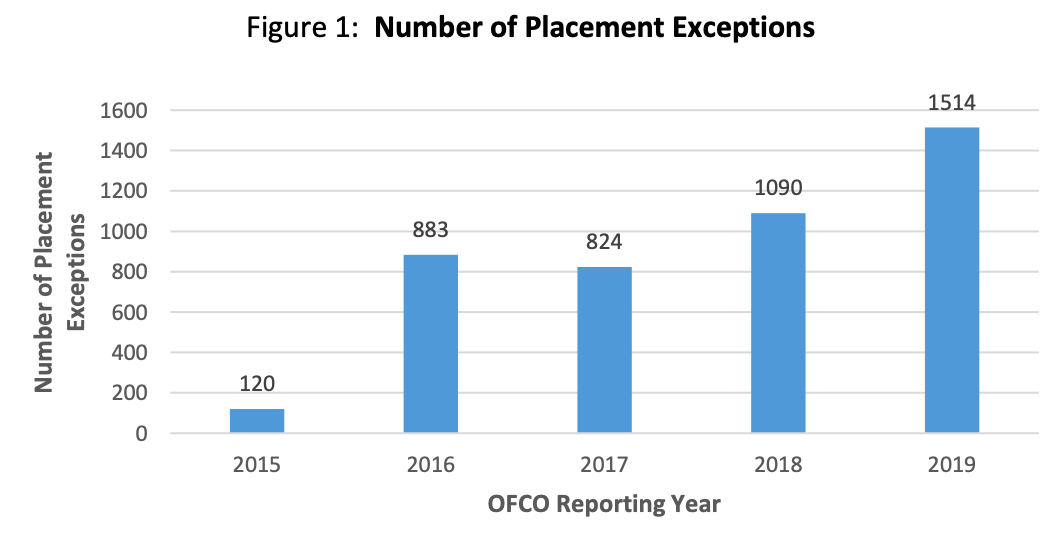

A record 282 children spent a total of 1,514 nights in hotels and state offices between September 2018 and August 2019, according to a recent report by the Washington Office of the Family and Children’s Ombuds. That’s nearly 39% more hotel stays than the previous year, and the highest number since the ombuds began tracking them five years ago. The trend continued through late last year, records show.

The steady increase in hotel stays, state officials say, is the legacy of recession-era budget cuts. Those cuts chipped away at treatment and support services for youth — in foster care and in the general population — who have mental illnesses, autism and developmental delays, addictions or behaviors that parents, relatives and foster families feel ill-equipped to handle. In particular, the Department of Children, Youth and Families says the state has too few group home spots for youth who need intensive treatment before they can return to parents, relatives or foster families.

The shortage of in-state options has also led the state in recent years to ship many of the hardest-to-place foster youths to out-of-state group homes, some of which have come under fire for mistreating kids. The state is now working to bring all foster youth back to Washington, where it can better monitor their care. But those efforts also are hindered by a lack of in-state group homes qualified to care for severely troubled youth.

“This is ‘chickens come home to roost’ for bad public policy and inadequate funding of both child welfare and public mental health during the past 10 to 15 years or longer,” said Dee Wilson, a former regional administrator in Washington’s child welfare system who now trains social workers.

Now legislators in Olympia are preparing to approve the second half of a two-year budget that, if Gov. Jay Inslee has his way, will continue to fall short, critics say, presaging more expensive overnights at hotels for foster youth.

Meanwhile, the toll on both children and state social workers mounts.

Children staying in hotels have made suicidal gestures and attempts, have sexually assaulted other youth, set fires in state offices and faced multiple arrests, the ombuds report says. Most spend their days sitting in Department of Children, Youth and Families offices instead of attending school, and they subsist largely on a diet of fast-food. “They report that being in a transient situation makes them feel no one wants them and they are unlovable,” the report concludes.

“This is just another level of trauma we are inflicting on these children,” Ombuds Director Patrick Dowd told the Department of Children, Youth and Families Oversight Board earlier this month.

To address the problem, Inslee’s proposed 2020-21 supplemental budget includes $7.6 million for 33 long- and short-term beds in facilities with “enhanced therapeutic services” for children with acute mental health, developmental and behavioral needs.

Some Democratic lawmakers say the governor’s proposal falls short, especially since the state recently had to move 26 of those foster youth out of Ryther, the children’s mental health agency. The Seattle nonprofit said it could no longer afford to serve foster youth at the state's reimbursement rate.

“It’s nothing short of criminal” that high-needs foster children are being sent to out-of-state group homes or kept in hotels, instead of in a safe setting like Ryther, said state Rep. Gerry Pollet, a Seattle Democrat whose district includes Ryther. “And the crazy thing about it is, it actually ends up costing far, far more.”

The Department of Children, Youth and Families spends roughly $2,100 per night for a hotel stay, most of that for two social workers and often a security guard to stay up all night and watch over a child. That’s nearly five times the $422 per night the state now pays in-state group homes, and 3½ times more than Ryther said it needs to break even. Since 2015, hotel stays have cost taxpayers an estimated $9.3 million.

Pollet and other lawmakers say they will seek to supplement the governor’s request in order to stem what the department calls a “crisis.”

Kids with mental illness, disabilities drive hotel stays

Children placed in hotels and offices include the occasional healthy infant or young adult on the verge of graduating from high school. But kids with “no significant barriers to placement” rarely show up among the more than 200 Department of Children, Youth and Families reports reviewed by InvestigateWest justifying individual hotel and office stays from 2016 through 2018..

More typical are youngsters such as the 17-year-old who functions at the level of a 3- or 4-year-old; the 11-year-old with “sexualized behaviors” who can’t be around small children; and the 7-year old “displaying significant disruptive behaviors, including destruction of property and assaults of staff and caregivers.” Many have been diagnosed with, and hospitalized for, a variety of mental health conditions that are blacked out in the records InvestigateWest obtained.

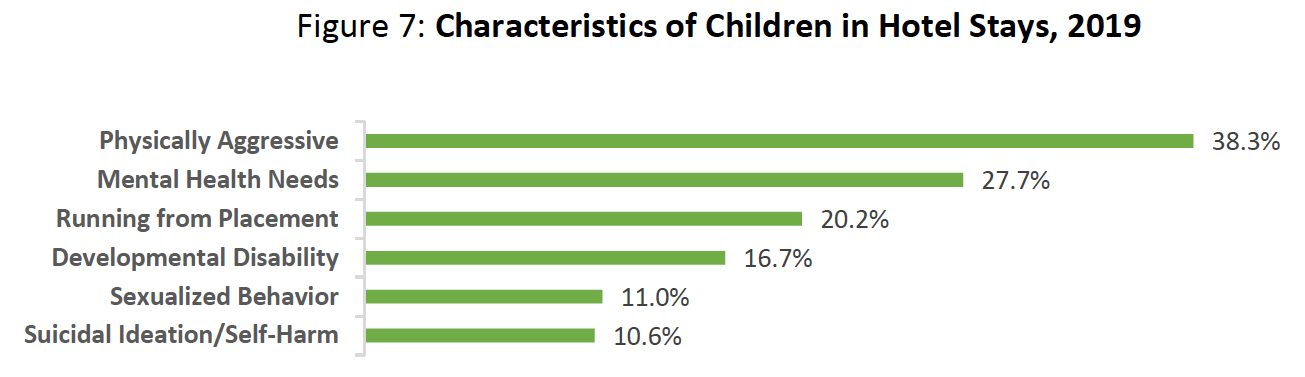

More than 38% of kids in hotels last year had a history of being physically aggressive, while nearly 28% needed mental health treatment, the ombuds found. Running away, developmental disabilities, sexualized behaviors and self-harm were also common.

But even children without a lot of special needs, when placed in hotels, begin to exhibit more challenging behaviors, said one state social worker in King County, who agreed to speak on the condition of anonymity out of fear of losing his job. Then those behaviors have to be disclosed to potential foster parents, he said, making the children harder to place.

The ombuds report found that a relatively small number of youths with the most extreme behaviors are driving the bulk of hotel stays.

Nearly 40% of children staying in hotels last year spent only one night there, often while transitioning between foster homes. Meanwhile, just 40 children accounted for more than half of all hotel stays and, of those, a dozen spent 20 or more nights in hotels. One child passed 77 nights in hotels during the year.

Social workers often note that children had been kicked out of or turned down by programs in the state that, in theory, are designed to handle them. Those include group homes and specially trained foster homes in the Department of Children, Youth and Families’ Behavior Rehabilitation Services for foster children with behavioral and mental health challenges.

“Very few BRS programs will take youth who require two or three line staff and a security guard to manage them overnight,” said child welfare veteran Wilson, who reviewed about 100 social worker reports on hotels stays at InvestigateWest’s request. These reports, he said, suggest that some of these youth need intensive residential mental health treatment in the Children’s Long-Term Inpatient Program. But, he added, capacity in the CLIP program hasn’t kept up with the state’s growing population.

DCYF, in its budget request to Inslee, suggested adding at least 10 CLIP beds especially for foster youth, on top of the current 84. Those were not included in Inslee’s proposal to the Legislature.

These are the kind of youths who, until recently, might have been sent to secure facilities in other states. After a watchdog’s 2018 report found abusive conditions at one Iowa facility where Washington had been sending foster children, Department of Children, Youth and Families Secretary Ross Hunter vowed to bring the state’s foster children home within two years. The number of foster kids out of state is down from a high of nearly 100 to 31 today.

That places “greater demands on existing placement resources” the ombuds report says. But it’s unclear whether more kids are in hotels because fewer are being sent out of state. Hunter said he didn’t think there’s a connection.

“If that were the case,” he said, “I would go back to putting them out of state, because I think it's better for kids to be in a stable placement, rather than being in a hotel or an office stay, even if that placement is out of state.”

Hotel stays appear to be concentrated in the department's regions that cover King, Whatcom, Skagit and Snohomish counties, according to the ombuds. But in other parts of the state, social workers might be relying more on night-to-night stays in licensed foster homes that function much like hotels, in that they keep children only from bedtime to breakfast. The department currently does not track such placements, but says it is building a way to do so. Sometimes those stays have cost taxpayers $600 a night, records show.

Those night-to-night stays also can be emotionally harmful to children, Hunter said. “The message you're sending to a kid there is, ‘There’s no place for you,’ ” he said. “And that’s not the right message. Kids need to feel welcome.”

Assaults on staff ‘not uncommon’

In November 2018, a 6-year-old staying in a hotel punched a social worker in the face five times and threw a cup of coffee at her, according to a Department of Children, Youth and Families Kent office supervisor’s email obtained by Investigate West. The boy also threw a water bottle at another worker, hitting her in the face. While jumping on the hotel furniture, he broke two lamps. Eventually, the workers called police, who took the child to the hospital for mental health observation.

According to the ombuds’ report, children assaulting staff in hotels and state offices is “not uncommon.” Neither the ombuds nor the department tracks how often assaults occur.

Staying in hotels and offices has a “dysregulating effect” on youth, particularly those with mental health issues, the report says, and can contribute to youths’ criminal behavior. “Some youth incur multiple criminal charges and convictions while in placement exceptions, which may impact them for the rest of their lives,” it says.

Unlike staffers in group homes, state social workers lack special training to handle the extreme behaviors some of these children exhibit, the ombuds report says.

And the after-hours workers who supervise kids in hotels are “almost always the least experienced.” Some are even students looking to gain experience.

Those overnight workers can and do use approved physical holds to restrain children acting out violently, according to Hunter.

State records, for example, describe a supervisor in an office wrapping his arms around a 7-year-old child who had been hitting the worker and had tried to run out the front door.

“We are required to restrain kids when they’re either dangerous to themselves or dangerous to other people,” Hunter said. Workers likely to be in that position are required to take training class, he said.

It’s only a matter of time before a child or worker is seriously injured, Wilson said: “This is just a tragedy waiting to happen.”

Among case workers, the stress of watching kids in hotels at night and in offices during the day also contributes to high rates of turnover, Hunter said. “Being in this kind of situation that they are not trained for and that they don't feel adequate to handle is one of the factors that people cite when they talk about why they leave,” he said.

And when kids experience frequent changes in social workers, it takes longer for them to return home or get another permanent family.

“It’s a bad spiral,” Hunter said.

Child welfare is ‘stop of last resort’

Not all children staying in hotels have been removed from their parents as a result of neglect or abuse. In some cases, parents have become overwhelmed by children’s needs and feel unable to care for them.

Social workers’ reports detail children whose parents refused to pick them up when they were discharged from the hospital or from juvenile detention, triggering a call to Child Protective Services. A growing number of children with developmental delays, particularly extreme forms of autism, are also winding up in the department’s care, the ombuds report says.

Post-recession cuts to community mental health resources and services for children with developmental disabilities are partly to blame, the ombuds concludes. Children can wait six months just to have their mental health assessed, Department of Children, Youth and Families regional administrators told the ombuds.

“These children are finding themselves in DCYF care,” the report says, “even though there are no allegations of child maltreatment, and the only parental deficiency is that the parent is unable to provide the level of extraordinary care the child requires.”

DCYF, Hunter said, has become the “stop of last resort.”

Hunter said he is working with leaders from the state Health Care Authority and Developmental Disabilities Administration to develop solutions.

Those include budget requests for more facility-based beds for both the most troubled foster youth and children with developmental disabilities. The three agencies, Hunter said, are also working to smooth youths’ transitions from one system to another — for example, children returning to foster care from mental health treatment — so they don’t land in hotels.

A search for solutions

Washington, like most other states, has long struggled to attract and retain enough foster parents. But, given the challenging nature of many of the kids staying in hotels, recruiting more regular foster parents won’t be enough, the ombuds notes. In fact, foster homes — which mostly aren’t equipped to care for children prone to starting fires, acting out sexually and so forth — sit empty while kids languish in hotels.

"It’s not as simple as, ‘Oh, we just need more licensed foster homes, and everything would be fine,’ " Ombuds Director Dowd said.

Department of Children, Youth and Families regional administrators interviewed for the ombuds report suggested creating a class of professional therapeutic foster parents who are trained and paid to be full-time caregivers for high-needs kids.

Wilson, long a proponent of professional foster care, agrees. “The only good alternative to residential care currently is professional foster care,” he said. Based on his review of department reports on youths in hotel stays, he estimates that perhaps half of them could have been cared for by professional foster parents.

At a meeting of the Department of Children, Youth and Families Oversight Board this month, Bobbe Bridge, a former state Supreme Court justice and longtime child welfare advocate, told her colleagues that it’s time for the state to revisit the idea of professional foster parents. The state studied the concept more than a decade ago before shelving it.

The state should also increase short-term “receiving” foster homes that keep bedrooms available for children in emergencies, both the ombuds and Wilson suggest. In fact, that was part of the department's original budget request to Inslee for this year’s legislative session, at a cost of $3.3 million annually. The department also asked for $721,000 to add workers dedicated to finding placements and services for the complex youth who might otherwise wind up in hotels, among other items intended to address the issue. Inslee didn’t include those in his budget request to the Legislature.

Wilson called Inslee’s budget “a pathetic, token response to the state’s foster care crisis.” It is “virtually an announcement of the intent to continue business as usual in a placement crisis that endangers both foster youth and DCYF staff,” he said.

Inslee’s office on Wednesday evening issued a statement to InvestigateWest that reads in part: “Funding to increase the number of placements for youth who need more intensive behavioral supports is an important first step to eliminating the need for hotel stays.” The statement provided no specifics. It said the state will “identify additional strategies” in the future.

The Legislature last year allocated an additional $38 million over two years for the first significant bump in the amount the state pays Behavior Rehabilitation Services group homes since before the Great Recession (the allocation fell short of the $50 million recommended by a rate study lawmakers had requested). The goal was to halt a decadelong decline in those services, which the department says has contributed to kids in hotels and out-of-state placements.

Those new, higher BRS rates went into effect last fall. Hunter said he expects agencies will respond by opening more beds.

Yet agencies in the Seattle area say that even that new rate, which is the same across the state, doesn’t account for the region’s higher minimum wage and cost of living.

Ryther would have lost about $1.2 million per year at the new rate, according to CEO Karen Brady. It decided it could no longer afford to do business with the state. Ryther continues to accept a small number of children on private insurance into its residential program.

A second Seattle-area child mental health agency, Navos, also stopped accepting foster children in 2017. Between it and Ryther, the state has lost access to 41 long-term BRS spots in Western Washington. That leaves about 10 BRS group home slots in the Seattle area, according to providers. The Department of Children, Youth and Families refused to provide the current number of in-state BRS beds.

Hunter said he anticipates that the governor’s proposal for 21 long-term “enhanced” BRS beds, which come with more money, will lure agencies like Ryther back.

Hunter said he would like to rely less on group homes, though he admits that might not be feasible. Child advocates say kids do better in family settings. Washington already places a smaller proportion of foster kids in group settings than the national average.

But, Hunter added, “I’d like to have more capacity in group homes, and have some slack, so I don’t have so many emergencies.”

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at http://www.invw.org/newsletters/.