Valicoff and some of his neighbors say they’re having trouble making ends meet in part because they can no longer find enough willing, cheap labor to work their fields. A federal guest worker program meant to supply farm owners with temporary help has offered little relief.

“It all looks good on the outside, but there's a lot of money owed on some of these properties,” said Valicoff, dressed in a baseball cap and tan cargo shorts as he looks over his property. “We can't sustain what we're doing. At some point, there's going to be breaking points here.”

Most of Valicoff’s workers are immigrants working in the United States through the federal H-2A program, which enables foreign workers, mostly from Mexico, to temporarily work on America’s farmlands. Workers in Washington and Oregon are paid $15.03 an hour wage, and provided housing, transportation and other benefits.

Growers unable to hire farmworkers already in the United States have increasingly turned to the H-2A program. Labor brokers involved in the program connect foreign workers with U.S. growers, who contract the workers for a season. Workers cannot leave their employer without losing their visas, and employers who fail to meet pay and housing requirements can be booted from the program.

Valicoff, 65, who was one of the first to bring the H-2A program to the state back in 2006, said he has difficulty working with local workers because they often attempt to haggle for higher wages.

“First thing they want to do is leverage you for more money every morning, because they know they got you up against the wall,” Valicoff said. “Now you got all this fruit you got to pick. You paid all this money to farm it all year long, and now you're going to squabble over two or three dollars? To them, two or three bucks is a win.”

But Valicoff also argues many landowners who use H-2A workers can’t afford to stay in the program without going broke. Some growers say they can’t manage to take part in the program at all. (Earlier this year, a federal court dismissed a lawsuit brought forward by the National Council of Agricultural Employers, which sought nationwide wage cuts for H-2A workers.)

Rosella Mosby, who owns Mosby Farms, a family farm outside Auburn, is one of those growers.

Mosby said she and her husband can’t afford to provide the worker housing required by the federal program. In today’s world, growers are forced to cater to customers who are used to Amazon and Costco prices, she said, and farms don’t make sufficient profits.

“We would use it if we could,” Mosby said.

Despite the costs of the H-2A program, an increasing number of growers say they have no choice but to use guest workers because of a domestic labor shortage. In Washington, the nation’s No. 4 destination for H-2A workers, growers requested approximately 25,000 foreign workers last year.

Now, the Trump administration is proposing changes in H-2A program rules that would loosen regulations. While growers argue the changes are needed to make the program less burdensome for farm owners, others say the new regulations could put workers at even greater risk.

Leaders with the United Farm Workers, the country’s largest farmworker union, noted that the new rules would allow employers to inspect housing conditions themselves. Some transportation costs would shift to workers, the union said, and wages for both foreign and domestic workers could become depressed.

At the same time, Washington state established a new office within the state’s Economic Security Department meant to monitor H-2A compliance and farm labor conditions. Within that office, a new eight-person advisory committee made up of farmworker advocates and employers will help oversee the H-2A program in the state, addressing both the shortage of local workers and working conditions on farms.

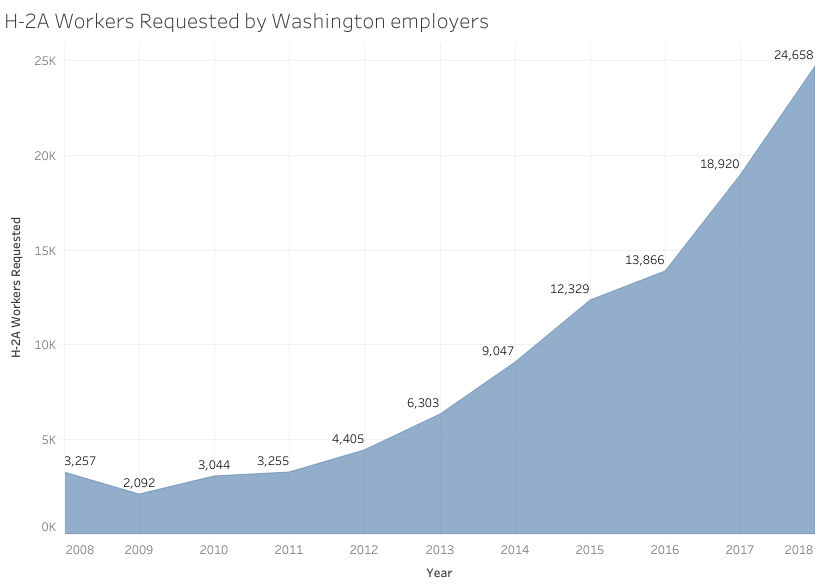

Agriculture, which has long drawn on a now-shrinking pool of skilled farmworkers without legal status, is big business in Washington. The industry employs more than 100,000 workers in the state, generating an estimated $7 billion in economic activity. Facing a labor shortage, though, growers have increasingly turned to the H-2A program, which has increased by a factor of 10 since 2007.

With $3.5 million in state funding for the new Economic Security Department office in the next two years, the advisory committee is expected to submit a report in October 2020 that includes recommendations on how to recruit domestic agricultural workers in Washington and better protect workers.

This committee is an "opportunity to actually work with the industry,” said Rosalinda Guillen, a member of the advisory committee and director of Community to Community, a farmworker organizing and advocacy group in Whatcom County. “It’s a very important step for us.”

Guillen said the need for oversight became apparent last year after Sarbanand Farms in Sumas, Whatcom County, was cleared of wrongdoing in the 2017 death of 28-year-old migrant worker Honesto Silva Ibarra. Sarbanand Farms was fined $149,800 for not providing required breaks and meal periods, though that fine was later reduced.

In a federal lawsuit filed the following year, blueberry pickers like Ibarra said they worked 12-hour days in the heat with little food at Sarbanand Farms. Workers also alleged they faced retaliation for protesting working conditions. Roughly 70 workers held a strike to call for better conditions, but were fired the next day. Most were sent back to Mexico immediately. The U.S. Department of Labor later barred Sarbanand Farms, part of Delano, California-based Munger Brothers, from using the H-2A program.

“We came at this from a very clear understanding that farmers’ lives are at stake,” Guillen said.

The H-2A program, she said, has always been prone to exploitation because “it just creates this isolated workforce.”

Valicoff’s use of the H-2A program has grown so much over the past decade that he recently bought a hotel to house hundreds of workers. He also rents rooms retrofitted with bunk beds to other growers.

Still, Valicoff maintains the H-2A program is, as he describes it, a little “too spendy.”

Back at his cherry orchard, Valicoff picked and ate his own produce while workers with their faces partially covered flitted about, working at a fast clip.

Valicoff explained some workers are paid by the bucket of fruit picked — a piece rate — because it encourages them to work faster and gives them the opportunity to make more than the $15.03 hourly wage mandated by H-2A rules, which are meant to ensure guest workers aren’t undercutting local workers’ wages.

“Why do we have to pay more than the minimum wage for foreign workers to come here?” he asked, while complaining that growers who use local workers can spend less and therefore make a greater profit.

Michele Besso, an attorney with the Northwest Justice Project and another member of the state’s new advisory committee on farm labor, said “many local workers are discouraged from taking a job because of the hoops and bureaucracy.”

Farmworkers are used to a more informal process for obtaining work, Besso said, but are often forced to apply through one of a number of Worksource offices throughout the state, rather than relying on word of mouth.

Besso is also concerned about conditions on the farms. She said she hears about H-2A workers struggling after being injured on the job, despite having workers compensation insurance. Some, for example, often lack transportation to get to medical help.

Meanwhile, Mosby, the owner of the family farm outside Auburn, said she is consistently about 10% to 15% short on workers.

“We don’t have a problem for paying people to work. It’s just getting people to work,” Mosby said, explaining that she pays her workers $13 to $14 an hour, plus an $1 per hour bonus for staying all season.

Even though she uses domestic workers, Mosby said she’s in favor of the H-2A program because she’d rather see growers use foreign workers and keep food local, rather than import more produce from elsewhere.

There is some research to support claims of worker shortages made by many growers. A 2018 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found that fewer laborers from rural Mexico are willing to take jobs on American farms. In addition, the number of undocumented immigrants already in the U.S., who once took farm jobs because they had few other options, has dropped in recent years, the report said.

Similarly, a 2017 report by the Washington Policy Center showed that more than half of farm owners reported financial losses because of “labor disruptions,” often because they could not get crops picked in a timely fashion to sell at the highest prices.

Valicoff said workers “might work today or tomorrow and then the next day not show up.

“You think Boeing could handle that? Who’s going to show up today to build an airplane? Well, that’s what we’ve got to deal with here,” Valicoff complained. “It’s even worse here because they could not have to build the airplane for a day or two, but we’ve got a perishable product.”

Guillen asserted that “there isn’t a worker shortage,” but that local workers in Washington state have been gradually displaced by H-2A workers. The natural migration of domestic workers from the Southwest, Guillen said, has been disrupted.

“Farms that pay good wages and treat workers halfway decent never have a labor problem,” Guillen argued.