West Seattleites became increasingly convinced the video featured a cougar — never mind that would be highly unlikely. More people attested to seeing a cougar around town, without photo evidence, in an age of rampant smartphone use. Some on Facebook and the West Seattle Blog cautioned people against fearing cougars and waiting for confirmation. Others advocated catch and release; still others cautioned against venturing near popular dog parks. Many made jokes about other types of mature “cougars” in the area.

In the coming days, it turned out that the video some people thought was recent was taken in September. As of January 14, Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife says the sighting is unconfirmed. On January 17, Dr. Brian Kertson, a Fish and Wildlife carnivore research scientist, said the animal in the video is “not a cougar. Pretty certain about this one.”

While a cougar in that part of West Seattle isn’t out of the realm of possibility, cougar sightings are extraordinarily rare in highly urban areas. But, as the state’s population booms and the edges of cougar country are developed, more experts are looking for ways to prepare the public for encountering a cougar. Ecologists and enforcement officers say they expect encounters to increase in Western Washington in semiurban areas. But they don't expect them to be dangerous — simply benign overlaps between cougar and human activity.

Living in cougar country

“People don’t realize that they inadvertently contribute to the issue, and they can help us be part of the solution,” says Dr. Rich Beausoleil with Fish and Wildlife.

When the department conducted a survey of human cougar knowledge a decade ago, 75% of residents reported having little to no knowledge of cougar behavior or ecology. While cougars tend to do a good job of removing themselves from situations, ecologists say, people handling a rare cougar interaction poorly could make an encounter dangerous.

“It's not time to freak out, it's time to take a step back and learn more,” says Capt. Alan Myers, a special operations captain with Fish and Wildlife.

For Kertson, cougars are functionally in everyone’s backyard — even if we’re not directly interacting with them and will likely never see one ourselves.

Kertson says that when he’s chasing cats in the foothills with downtown Bellevue and Seattle on the horizon, he sometimes thinks, “Man, there's people banking and commuting and having lunch with colleagues or friends or, building skyscrapers, and I'm tracking a cougar a stone's throw away.”

About 40,000 square miles of Washington state are considered cougar habitat, Kertson says — effectively all but large swatches of flat and open south central Washington. They seek out spaces that offer good cover with thick brush, steep canyons or dense trees, and have plenty of prey to stalk, especially deer and elk.

Where space is available, they’ll take it for their home range. Male cougars can claim an average of 200 square miles, and there are usually only four of these elbow-room-seeking creatures per 100 square miles of habitat.

Cougar-human encounters occur most likely in the wildland-urban interface. Generally, this is where suburban, exurban and rural areas intermingle with or abut wildlands like forests, grasslands and sagebrush steppe.

Kertson and his colleagues conducted research in Western Washington a few years ago that found that along the western slopes of the Cascades, cougars spend 16% of their time on average in areas with at least some residential development — not the urban core, but suburbs and exurbs.

Amid booms in development and urban sprawl, the wildland-urban interface, or WUI (pronounced woo-ee) has grown, too, with about one in three American homes touching or inside these largely undeveloped areas, according to a national study evaluating wildfire risk.

In Snohomish County alone, 127,000 people live in an expanding WUI, according to 2018 data.

Cougars use these spaces because there’s enough habitat and food. “Combine that with the fact that cougars are arguably the most adaptable successful large carnivore on the planet … if you drop a couple of houses in the forest, they can roll with that,” Kertson says.

Mikey Ramirez, who lives near Index in Snohomish County, has resided in Western Washington for about 40 years and had his first cougar encounter here about 35 years ago. Most of his handful of encounters have been while hunting, but about eight years ago, a cougar showed up at his home when he lived in Issaquah in a house backed up against the Cougar Mountain Wilderness Area.

“I stepped out on my deck and this lion was underneath it,” he says. As he ran back into the house, he says, his 6½-pound Maine coon pet cat chased the cougar off the property. “She just had a marble missing where she wasn’t afraid of anything.”

Ramirez acknowledges wildlife like cougars have first dibs on the neighborhood.

“I look at [cougars] as being here first, OK? And then we come in, we build cities and put concrete down in the valleys where they used to winter and all that,” he says.

Cougars make loops through urban environments all the time, even in places like downtown Seattle, says Myers, the special operations captain with Fish and Wildlife. There are some high-profile instances of cougars wandering into heavily urban areas, including the cat that lived in Discovery Park for three weeks more than a decade ago and a cat that traversed Mercer Island for a few days several years ago. But when the occasional cougar does wander into a densely urban area, it’s almost definitely a young male erring in trying to stake out a new home range, experts say.

“They just sort of pick a direction to go, and they go,” Kertson says. If they pick west, they wander into places with lots of people. “They’re following these habitat cul de sacs, but they don’t know they’re corridors to nowhere. As far as they know, on the other side is Shangri-La filled with ample deer and elk and reproductive females and all that stuff, when in fact … it’s downtown Renton.”

Cats in urban areas hunker down in stands of forest by day, and hustle out at night. The more densely populated the place, the shorter the stay. These cats figure out within a few days that they have better places to be, but then have to avoid getting treed by mission-oriented German shepherds or run over by cars. Making it back across Interstate 405 is a particular challenge, Kertson says.

Habitat loss certainly doesn’t help cougars. Look no further than California to see the worst effects of urban sprawl and highway expansion on habitat connectivity and wildlife corridors. But that’s not what is driving them into Washington’s urban areas, Kertson says. What’s more, “cougars are probably one of the few species that are going to be OK with climate change,” Kertson says.

“Basically, west of Lake Washington is not going to be a place where cougars would be able to eke out a living,” says Dr. Robert Long, conservation scientist and director of Woodland Park Zoo’s Living Northwest Program. “But we live surrounded by cougars, so clearly, they could show up in just about anyone's backyard at any time, but that doesn't mean it's going to happen and the probability is very low. And then the probability that there's going to be any kind of negative interaction with a human is even lower.”

Running into cougars

Whether we actually run into animals in the places they frequent is another thing.

Cougar sighting data is muddy to begin with, similar in some ways to UFO sightings. On the one hand, people aren’t great at identifying cougars, which makes drawing any inferences from reported sightings unreliable. There’s also the complicating factor of security camera footage: Have these animals always been around, and we just didn’t realize it?

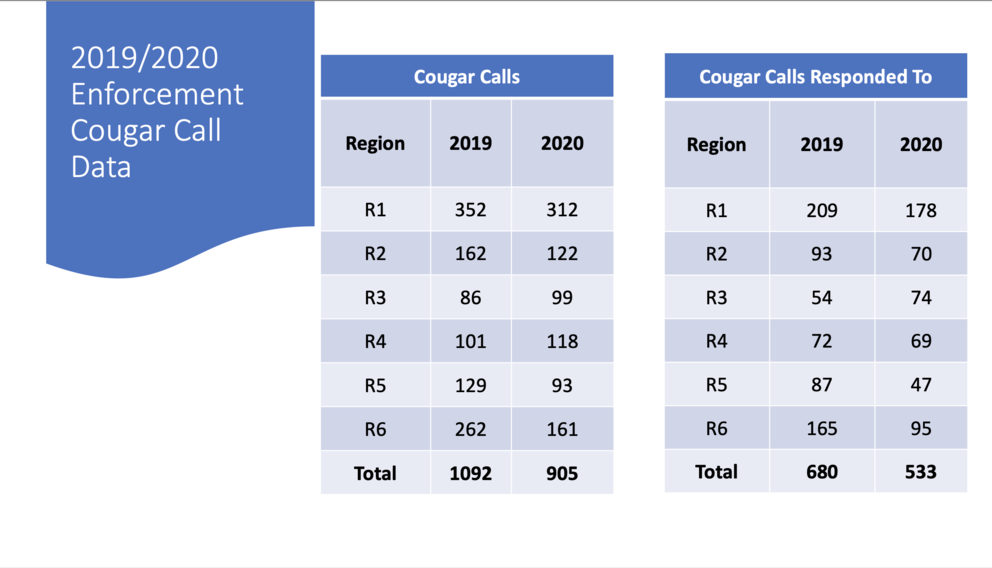

After the state passed an initiative in 1996 to make baiting many large carnivores a gross misdemeanor, more people reported interactions. But those sightings steadily declined over the next decade. “The question has always been whether or not those interactions that we saw post-initiative … were a real increase, or if that was a function of cougars being on the forefront of people's minds,” Kertson says.

The first fatal cougar attack in Washington state in 94 years came in 2018, and it prompted a lot of the conversations people are having today about human-wildlife interactions, Kertson says.

But over the past 30 years, there have been definite increases throughout the cougar's range in the US, Kertson says, though for about a decade leading up to 2017 they were declining in Washington state. “The real question is exactly why.”

Kertson is on a panel along with Wildlife Deputy Dir. Mick Cope and Wildlife Chief Scientist Donny Martorello that will present to the Fish and Wildlife Commission later this month about what drives cougar-human interaction. Kertson says, it’s strongly suspected that it’s not changes in cougar population alone—or even mostly—that drive increased interaction, but rather cougar activity paired with human activity and development. "I do strongly suspect that residential patterns are more important, but I cannot say that definitively from my work or anyone else’s," he says. Cougars aren’t entirely blameless, but more recreation close to wild areas and more infrastructure along the wildlife-urban interface, brings people and cougars closer together.

Over the past few decades, more people have been hiking, biking, running all over Western Washington, bringing more people into core cougar habitat. And if they encounter that cougar, they most likely have no idea what to do, Kertson says, although he stresses the risk to recreationalists in cougar country is still exceptionally low.

For the most part, cougars aren’t really interested in us. When they do encounter people, they flee and de-escalate the situation. People who encounter a cougar acting erratically should do the opposite: Face the cougar, try to appear large, make noise and stand their ground until the cougar leaves. "In the exceptionally unlikely event the cat attacks, try to stay on your feet and fight back aggressively," Kertson says.

In the meantime, don’t accidentally attract cougars to your yard by feeding deer and other prey, animals experts advise. Taking in livestock at dawn and dusk, and monitoring them and other pets when they’re hanging out outside, prevents them from becoming prey, too.

Ramirez learned a lesson about securing livestock the hard way. As a child in Sultan, he had a pet goat that wore a rope around its neck. One day, Ramirez couldn’t find his goat, he says, so he followed the rope, and eventually found the end of it buried in the ground. “Something killed it, dug a complete hole and totally buried my goat,” he says. “It was a lion because I don’t think a bear would have done that.”

Fish and Wildlife’s Cougar Safety Team, launched about three years ago, is working to help people feel safe in cougar country by updating and expanding outreach and education, and rolling the newest science into enforcement response strategies.

About 40,000 square miles of Washington state are considered cougar habitat. As urban sprawl and wild-land urban interface areas widen, the chances of human-cougar interactions grow, though experts say the probability of such encounters is still very low. (AP Photo/Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, File)

Kertson isn’t aware of anyone attempting to academically predict trends in cougar-human interaction in Washington state. But he and colleagues are “pretty confident” that human-wildlife conflict, including and beyond cougars, is only going to become a bigger issue. “To me, it is going to be the predominant wildlife management issue of the 21st century,” he says.

“[Increased interaction] is entirely dependent upon people, and there is no way to predict that other than to say hotter summers and colder winters tend to result in more interactions,” says Fish and Wildlife bear and cougar specialist Rich Beausoleil.

Fear is human

Predators elicit a primal sense of fear that complicates accepting ideas about how we can coexist with them. One of the main challenges is helping people unemotionally dial in their risk perception of living with cougars. Too much knowledge without good risk perception — like security camera footage without understanding cougar behavior — can exacerbate concerns, Myers says.

One reason there’s been good coexistence between humans and cougars historically is because humans have largely lived in ignorance. “It’s the two-legged animals that are the ones that you should worry about the most. Not the four-legged ones,” Myers says.

Given that, he believes the decades-old state policies for responding to cougar encounters (the dangerous wildlife policy and the wildlife conflict policy) do not reflect modern knowledge or reality. The policies in place don’t account for human culture. People in larger urban centers tend to stress relocating cougars instead of killing them, which doesn’t always turn out well for the cougar, while people in rural areas tend to push for more aggressive action, Myers says.

Not every response requires a badge and a gun, says Myers, who has a goal of better integrating the state’s 16 wildlife conflict specialists into the response strategy for cougar sightings to help people feel safe after enforcement secures situations. “But this isn’t something we can necessarily manage our way out of,” Kertson says.

He believes a lot of the decisions about how we handle cougars in the future will be driven by what people are willing to give up — or to reframe as benefits to living here. “Do you value this feeling of perpetual safety over having a fully functioning cougar population? Or are you willing to take some small but innate risk of having these animals live close to us?” Kertson says.

Helping people grasp their real risk around cougars means listening to their fears, and being emphatic, experts like Seattle University’s Mark Jordan say.

“There are some very basic things everyone can do to reduce conflict, like making sure there isn’t any food outside on their property and keeping their pets on leash or indoors. But I think we need to articulate that message in a way that acknowledges people’s concerns about coexisting with wildlife,” Jordan says.

While even one fatality is too many, cougars have caused about the same number of fatalities in the past 90-plus years — two — as moose and mountain goats, Beausoleil says. And cougars in urban areas aren’t remotely the animal most likely to pick off your pet, Myers adds.

“I constantly tell people, your little dog or cat is at more risk from the dozen coyotes that are in your backyard than they are a lone cougar who may have been traipsing through looking for some blacktail deer or rabbits,” he says.

Update: This story was corrected from acres to miles in describing the Washington state cougar habitat. It also clarifies Capt. Alan Myers’ reflections on cougar enforcement to compare rural and urban perspectives instead of framing things as an “east/west” issue.