Hanson and her husband invested more than a decade and thousands of dollars into this property, driving nearly 200 miles from Chehalis on weekends to build fences and whatever else they could afford as the years went on.

She might not be walking distance from everyone, but recently Hanson and her neighbors in rural Klickitat County have become closer than ever. They’ve banded together to fight a new giant knocking at their doors: big solar.

“We were horrified [when we found out about the project],” Hanson says. “[Turns out] because of the nice, new, shiny substation there, this is prime area for them to develop solar.”

Hanson’s retirement home would be hemmed in on three sides. No more idyllic rural views, she says. Just rows of solar panels.

“It’s just all consuming. It’s all you can think about. You dream about it at night, think about it during the day. It’s just a horrible feeling,” Hanson says, choking back tears. “This is not what we thought would happen when we retired in July.”

If approved, the utility-scale solar farm would be the largest in renewable-friendly Klickitat County and in Washington. Some say its potential location doesn’t take one important thing into account: environmental justice.

Documents given to Northwest Public Broadcasting show several developers considering solar projects near the Knight Road area — and Amy Hanson’s land — in Klickitat County. The spot is attractive to solar companies because they can easily connect to the Bonneville Power Administration’s Knight Substation.

No solar projects have so far submitted a final proposal in the Knight Road area. The county also recently put a “pause” on commercial and industrial solar project developments that require a special permit, which includes this same area that’s caused the neighbors’ uprising.

One lease proposal letter says Invenergy, a renewable energy company with other large-scale projects in Washington and Oregon, is “in the process of leasing approximately 2,400 acres around BPA’s Knight substation for solar facilities.” Right now, Washington’s largest solar facility — under construction in Klickitat County — is about 1,800 acres.

The company did not respond to requests for comment.

Thursday protests with C.E.A.S.E.

Every Thursday, a growing number of activists line Goldendale’s Columbus Avenue. (Every Tuesday they call into the county commissioners’ weekly meeting. “Keep comments to seven minutes” is a common refrain from the three men during allotted public comment time — the reminder was even jokingly reinforced as one commissioner chatted with the sign-wielding group.)

Their bright yellow signs shout “stop solar farms,” the same slogan that lines fences near where the potential solar project could be built.

On a recent weekday, Greg Wagner parks himself in front of the entrance to Goldendale’s post office. He’s asking people to sign a petition demanding more regulations for solar projects in Klickitat County.

“I signed your petition and everything. I’ve got a couple options for you,” one passerby says, giving a thumbs up as he sees the solar protest signs.

“What’s your beef with solar?” another man asks someone wielding a “stop solar farms” sign.

Wagner founded C.E.A.S.E. — Citizens Educated About Solar Energy — last October to oppose the project that could soon land in his backyard.

“They do all these different environmental protection studies. I mean, it’s plants, and it’s birds, and it’s water drainages — all kinds of environmental impacts,” Wagner says. “But they never do a human impact. They never look at how it’s going to hurt the people that have to live around these things.”

It’s not just the viewsheds people worry about. Yakama Nation tribal members Elaine Harvey and her cousin Tina Antone wave as cars honk their support.

Yakama Nation members Elaine Harvey, left, and her cousin Tina Antone say new solar developments in Klickitat County will displace land where they can find three different types of roots. They say they’re also concerned about what industrial-scale solar would do to wildlife habitat and migration corridors. (Courtney Flatt/NWPB)

They say the Knight Road project would cover grounds where they can gather three different types of roots.

“We’re worried about everything. It’s for our future generations because where are they going to get their food if we don’t say anything? If we don’t hold a sign? We’re [not] just going to let it happen,” Harvey says.

Currently, some farmers allow tribal members to gather food on their private land. Antone, who’s wearing a white mask with “Stop Solar” written in black Sharpie across the front, says once corporations lease the land, the Yakama Nation’s friends are gone.

“I’m for good energy, but if it’s industrial, that’s something else,” Antone says.

Bearing the burden

Down the road, Goldendale resident Sandy Crosland smiles at passing cars. She says the people of Klickitat County will bear the burden of this project.

“This community is going to bear the brunt of all the consequences — there are many — but none of the benefits except taxes. The tax base is going to go up, but you’re going to do that on the backs of your own citizens. Is that fair and equitable enough?” Crosland says.

It’s a big question as more renewable energy projects come online.

Washington has pledged to eliminate fossil fuels from its electricity generation by 2045. Even with a wealth of hydropower, electricity generation is still the third largest source of heat-trapping emissions in the state — behind transportation and buildings.

Oregon will require half of its energy to come from renewable sources, like wind and solar, by 2040. The state’s renewable goals were meant to drive more clean energy generation. Therefore, goals don’t grandfather in decades-old hydropower, unless there’s been efficiency upgrades, or a dam has been certified as low-impact since 1995.

Sanya Carley is a professor at Indiana University’s O’Neill School of Public and Environment Affairs. She studies the equity implications of a clean energy transition.

Communities of color or lower-income communities are often most disproportionately affected as the nation transitions to cleaner energy sources — more burdens on the backs of those who’ve already been pinned down by dirtier energy projects, Carley says.

“It’s the same communities that have been located right next to power plants or right next to highways, for example,” Carley says. “They’ve all borne these terrible externalities from the fossil fuel reign. And they’re the same ones that stand to either not benefit from the transition or to be completely cast aside.”

Opposing voices aren’t just from people shouting about projects in their backyards. Carley says her research shows NIMBYism — the idea that you support something in general, just not near you — isn’t really a thing, socially speaking.

“There’s this derogatory undertone of the concept of NIMBYism that suggests that people are somehow irrational. Like if it’s near them, then they all of a sudden don’t like it. But we find that it’s not irrational at all,” Carley says.

Instead, the researchers take into account how people value their surroundings.

“It’s the value of their environment. It’s the value of their home and what it means to them, what it means to them culturally, what it means to them historically. Once we account for all these things, that irrational concept of NIMBYism just completely disappears,” Carley says.

She says one big aspect that needs to be changed as states transition to cleaner energy is called procedural justice.

“It’s actually thinking about who you involve in these conversations [about proposed renewable energy projects]. We know another injustice with the energy transition is that those that are harmed tend to be the ones that are not involved in the decision making processes. [They should be] included or allowed to lead or have a voice,” Carley says.

One way to do that is to start renewable energy project proposals “from the bottom up.” Build trust with local communities and make a real effort to reach out and include people who might be affected by renewable energy projects.

Greg Wagner founded C.E.A.S.E — Citizens Educated About Solar Energy — in October 2020. He has spent recent months combing public documents in his fight against the large-scale solar farms that could be built near his property. Klickitat County has now enacted a moratorium on solar development in that area for up to six months — in large part because of concerns raised by C.E.A.S.E. (Courtney Flatt/NWPB)

The idea has been tried before, in California’s San Joaquin Valley, where people affected by nearby large-scale solar projects sat down and found areas that would cause the least amount of conflict. They create maps, where you can clearly see solar sites that wouldn’t be ideal and those that would be better. People learned how to better talk to each other. Concerns could be addressed earlier on.

Out of the study area, the group identified roughly 5% of the county that would be less controversial and more open to solar development.

A pilot program in Washington’s central Columbia Basin would similarly gather people, allow them to discuss their concerns and map out areas that could be best suited for large-scale solar. Places away from homes, not on lands significant to tribes or prime agricultural ground.

During the recently adjourned 2021 legislative session, the program received $500,000 in Washington’s operating budget. That money will be available in July 2023. It was nearly funded in 2020 but was struck from the budget during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Todd Currier directs the Washington State University Energy Program, which will house the least-conflict solar-siting pilot program. Currier says it’s important that the pilot program focus on a small section of Washington so that local people can talk about the potential conflicts of large-scale solar siting.

In the end, they would “produce maps that are fairly precise about where there’s more and where there is less conflict of various types. How regulators use it, how counties use it, how developers use it, is all up to them, Currier says. “We’re trying to provide information to this kind of process, not tell anyone what to do,” he says.

Currier says he’d also like to look into dual-use solar projects, where the solar panels could coexist with other land uses, like grazing.

“If we can’t build solar at large scale, and we can’t build much more wind at large scale, I’m not sure how we meet our carbon reduction goals for the electricity system,” he says. “So it’s really important that we find ways of being friendly to renewable energy development, while at the same time not overly compromising on our other values.”

That’s a big goal for Gov. Jay Inslee, according to Tara Lee, a spokesperson. Washington’s Energy Strategy starts with a chapter on equity. It says public meetings don’t mean that something is equitable. People who might be harmed must be sought out.

“It’s important for clean energy, for tribal rights and community well-being, for workers and for our economy to develop good processes that appropriately site the facilities we need to reduce climate pollution and build out our clean future. We believe when we do it right, all Washingtonians will benefit from stepping up and doing our part to help building this clean future,” Lee wrote in an email.

Finding improvements

Washington’s recently passed Clean Fuels bill directs the state departments of Ecology and Commerce to find improvements for industrial-scale renewable energy permitting processes. That includes finding areas that would be less environmentally harmful for “highly impacted communities.”

Ecology must also continue to consult tribes about proposed projects, as well as bringing in “businesses, local governments, community organizations and environmental and labor stakeholders.”

“We’ll have to figure out how the environmental justice task force figures into the work, but of course those communities will have an important voice,” Lee wrote.

Washington and Oregon both have state-level energy facility siting councils. These groups oversee locations and permitting for large-scale projects. In Washington, renewable energy projects can opt in to be reviewed or certified by the council — something various community members say bypasses local control for energy projects. The council makes recommendations to Inslee about a project’s future.

In Oregon, the state Department of Land Conservation and Development has set some rules for siting renewable energy. The goal was to help develop projects in areas that aren’t as important to wildlife or for farming.

The Knight Road solar project near Goldendale could be built on productive grain and hay fields, which concerns some local farmers. If the solar project were developed across the Columbia, in Oregon, there would be more restrictions.

In areas with “the best soil for farming,” Oregon rules state, solar panels can take up 12 acres. There are some exceptions to that limit, including approved plans for solar development where farming can coexist. Other land with poorer soil and no water rights can be used for solar farms that are up to 320 acres.

Those sorts of considerations are what people living in Washington near Klickitat County’s Knight Road would like to see their county commissioners implement.

Energy equity concerns not only where renewable energy projects are placed, but also who has access to carbon-free energy. In the Northwest, a lot of access issues can crop up for tribal members and rural residents.

“We need to actually change how we design and site technologies upstream of the decision-making process so that they can be more valuable to communities,” says Rebecca O’Neil, who studies energy equity at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “Because just building energy projects or a low carbon grid is a good ambition. But we can do better than that.”

Seeing an opportunity

Washington’s Klickitat County is one of the more renewable energy friendly areas of the state. That’s partly because county planners saw an opportunity with renewable energy technology.

They created an energy overlay zone that makes it easier to build renewable projects in areas where there’s already been an environmental analysis. Opponents like to say the zone mostly focuses on wind and that solar power is almost offhandedly thrown in without much guidance.

Residents near the Knight Substation say more rules need to be established for solar projects. They recently pushed for — and received — a moratorium on new solar projects that would connect to the substation that’s down the hill from Amy Hanson’s property.

Klickitat County Commissioner Dan Christopher says there needs to be talks over whether and where large-scale solar projects should be built. He pushed for the moratorium, getting it passed 2-1 on his second attempt. The moratorium could last up to six months.

“I mean, there’s pros and cons to a large-scale solar development,” Christopher says. “Yes, it’s ugly as sin. And people have to look at it, OK? It provides green energy. Great. But do the people of this county get to reap any of the benefits of that green energy? Do they get any of that power? No.”

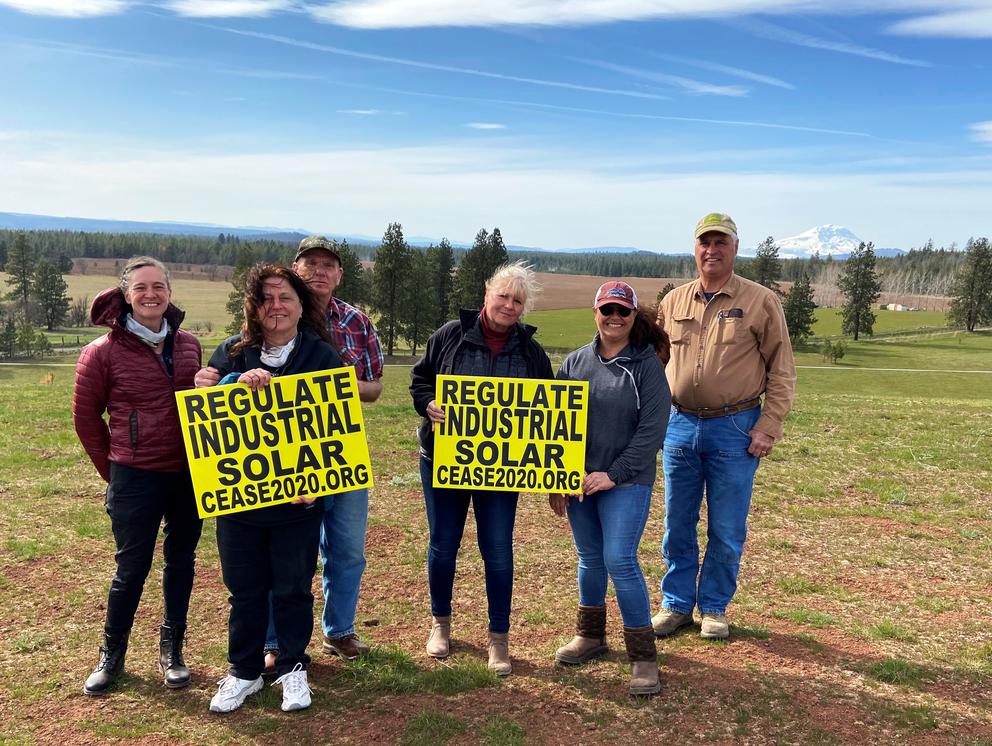

Members of C.E.A.S.E — Citizens Educated About Solar Energy — gather on Amy Hanson’s land, center right. Hanson and her husband, Russ, hoped to build their retirement home here, but stopped their plans once they learned their property could be hemmed in on three sides by solar panels. (Courtney Flatt/NWPB)

The county would get tax revenues that provide other services, like county road repair and help for the local hospital, school and fire districts.

“We can provide more services to our people than other counties that don’t have that [tax revenue]. But the people need to decide, do you want the tax revenues so that we can provide more services and look at that ugly thing? Or do you not want to have the ugly thing? And then we’re going to have to cut some of those services,” Christopher says.

At the March 16 county commissioner’s meeting, commissioner Jacob Anderson said the moratorium could do more harm to the county by pushing away business. With or without the hold, solar companies could still get approved through the state siting process, Anderson said.

“The last thing I want to do is push any company or project to go through the state process. Most every problem that we have in government is our unintended consequences,” Anderson said at the meeting.

The moratorium pertains to parts of the county not encompassed in its energy overlay zone — that includes the area that’s kicked up the most fuss about this potential solar farm. The hold on solar projects didn’t come in time — or in the right area — to pause the state’s largest solar project now under construction.

Another project

The Lund Hill Solar Farm will be the largest in Washington once it’s built, covering around 1,800 acres in Klickitat County. Most of that is former grazing land.

The project was the first in Washington to lease 480 acres of state trust lands from the Department of Natural Resources. The grazing lands will generate more revenue as solar leases for the state. (Yearly, up to $300 per acre from around $2 per acre from grazing.) That would then be put into school construction across Washington.

“Our goal is to produce 500 megawatts of solar power on public lands by 2025,” Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz said at the time. “The clean energy we generate reduces pollution and builds energy independence in our communities. And it also creates family-wage jobs in parts of our state that need them the most.”

The project is expected to come online in mid-2021.

Once completed, it will surround Darby Hanson’s home. Hanson (no relation to Amy Hanson) strongly opposed the project before it was approved.

In comments on Lund Hill’s final environmental impact statement, Darby Hanson wrote: “These large-scale solar projects are not merely ‘noticeable’ in their words. They will not just be ‘a thin dark line on the horizon’ from a mile away, since they track the sun and will continuously change throughout the day. Out here, a mile is nowhere near the horizon. The large dark patch will stick out like a sore thumb from the more distant viewpoints. They will be almost all you can see from the close viewpoints. They will be a (dominant) feature out almost every window of our house, especially once a presumed phase 2 is built to the south.”

Reviewers responded that it would be unlikely to see the entire project, unless someone was at an elevated spot. On flatter ground, people would most likely just see the first two rows of panels. A visual simulation “shows that the solar modules would appear as a thin, dark line on or near the horizon,” the response says.

Many members of C.E.A.S.E. — the group fighting new solar proposals — say Darby Hanson’s fate could be their own. Large-scale solar is different, they insist. It’s not a group of wind turbines spaced out over miles. It would be contiguous solar panels, over thousands of acres.

Rocel Dimmick recently moved to the Knight Road area after her boyfriend got a new job with the railroad. Housing is slim in the county; they couldn’t find a place to rent or house to buy. So they decided to build something on a piece of property they really loved. Then they learned about the potential solar farm. They’ve yet to begin construction.

“I feel like it’s next to being homeless,” Dimmick says. “I mean, it’s a home, but it’s not not my home. That’s where it’s our place right there,” she says pointing downhill toward the substation.

Right now, Dimmick says, solar companies can set up shop within 500 feet of a home, not a property boundary. She says that basically means a home on her smaller piece of property could be incredibly close to solar panels. Property lines are supposed to establish barriers between neighbors, Dimmick says, not homes.

“People are becoming economic casualties. They’re investing their retirements, their pensions, to have a part of this [land]. That’s the most heartbreaking thing,” Dimmick says.

As people move out of urban areas, less of this land is available to farm. It’s harder to work around solar than wind, says small farmer Dave Barta.

“If [renewable energy projects] are properly sited, there’s not a problem. Put them in the right spot, then we wouldn’t be going through this,” Barta says.

So what’s a better area for these solar panels? C.E.A.S.E. suggests the wide open land of the Hanford site, north of Richland, away from homes and crops.

Now, Amy Hanson says she and her husband are in limbo. They don’t want to stay, but they don’t want to sell to some other unsuspecting buyer.

“We worked hard our whole adult life. We wanted to retire to what, for us, was paradise,” she says. “And now it’s just turned into a nightmare.”