The only solution is “to pull your net out, and the jellies just fill your boat, and you are scooping them out,” said Peters, a member of the Squaxin Island Tribe who serves as the tribe’s natural resources policy representative. “Jellyfish can be a real pain in the butt.”

Moon jellyfish occur naturally in Puget Sound, but in recent years unusually dense clusters stretching the equivalent of several city blocks have appeared.

These massive jellyfish “smacks” are one of the more visible signs that Puget Sound is ecologically out of whack. Another obvious sign of the imbalance: profusions of one-celled marine creatures blooming in such abundance that their reddish-orange blobs can be seen from space. These changes are part of a far-reaching ecosystem breakdown that also is seeing oysters struggling to form proper shells, clam beds closed, salmon stocks crashing and, at the top of the food chain, orcas starving.

Inadequately treated human waste is an important — and growing — cause of that disruption, scientists say.

Dumping this sewage causes a chain reaction that exhausts the water’s supply of oxygen, leaving marine creatures essentially breathless. Since 2006, between 19% and 23% of Puget Sound has failed to meet oxygen standards mandated by the federal Clean Water Act, according to a 2019 state report.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories here.

These and other developments highlight a pressing state of environmental decay in Puget Sound that require a multibillion-dollar solution.

Environmentalists have sued the state over the sewage-treatment plants’ waste dumping, pointing out that the last time the Washington Department of Ecology required major modernization of wastewater plants was in 1987 — and that was an upgrade to a technology first deployed in the early 20th century.

The Department of Ecology is now on course to require plants to adopt better sewage treatment methods developed in the 1980s and used for decades on the East Coast. That technology is capable of removing “nutrients,” especially nitrogen, that act like fertilizer and feed Puget Sound’s algae and jellyfish explosions. But most of those upgrades on Puget Sound-area plants won’t be completed until at least 2035.

Representatives of wastewater treatment plants say they are concerned about rushing costly fixes.

“These are very large, complicated plants, not to mention expensive,” said Jeff Clarke, commissioner of the Mukilteo Water and Wastewater District and a member of a committee of experts advising the state. “And if you think it’s expensive to do it right, how about doing it wrong? If we spend a ton of money, it turns out that it wasn’t needed…. It really eats into public confidence.” By one estimate, this could cost households from $11 to $23 a month.

Pushing hardest on the other side of the argument is an environmental group that has sued Washington — so far unsuccessfully — to do a better job cleaning up sewage before it reaches the sound.

“What price do people put on having live orcas and salmon and Dungeness crab and all the things that people enjoy or want to protect … in Puget Sound?” said Nina Bell, executive director of the Portland-based Northwest Environmental Advocates. “Cause that’s what’s at stake.”

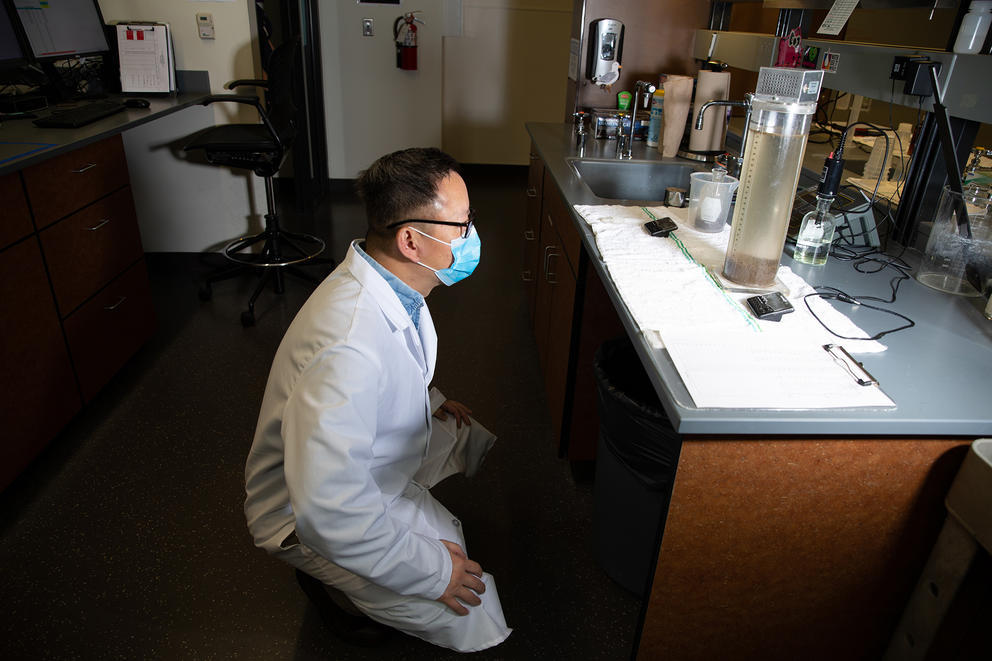

Paul Jue, water quality analyst at LOTT Clean Water Alliance, looks at the volume of settled sludge in the settleometer to gauge how the treatment process is working in Olympia, Washington, October 15, 2020. In the settleometer, microbes are found in the dense brown matter at the bottom, having settled out of the clear water above. LOTT depends on thousands of pounds of bacteria to help remove nutrients from the wastewater at the Budd Inlet Treatment Plant. (Karen Ducey/InvestigateWest)

‘Like tomato soup’

When Christine Goodwin gazed out at Holmes Harbor from her waterfront home on Whidbey Island in June, she saw a familiar orange-red stain covering the water. The telltale hue and musty smell told her right away that the algal bloom was caused by a type of one-celled marine organism called Noctiluca.

“It looks like Campbell’s tomato soup,” Goodwin said. Such blooms were a common sight in the harbor two decades ago, when, as president of Friends of Holmes Harbor, she began fighting to curb industrial runoff. Conditions improved. But now Goodwin notices the blooms are growing larger again.

“It saddens me, disappoints me,” Goodwin said.

Humans are fouling the only homes that fish, crabs and other marine life have, she said. But those creatures “can’t pack up in a U-Haul and move away,” she said. “They can’t defend themselves.”

Puget Sound’s algae and jellyfish explosions are fed, researchers say, by the chemical element nitrogen. Nitrogen is everywhere — the seventh most abundant element in the Milky Way, scientists estimate.

But here on Earth, where nitrogen makes up about three-quarters of the atmosphere, its natural cycles have been profoundly disrupted by human activities.

Secondary clarifier basins at LOTT Clean Water Alliance dramatically reduce the flow of wastewater dramatically midway through the cleaning process so solids and bacteria can settle. At this point, the nutrient removal process has been completed. In these basins, microbes that have helped with that work settle out so that treated, clean water can proceed to the final step of ultraviolet disinfection. (Karen Ducey/InvestigateWest)

Nitrogen has always been present in human and animal waste. Most wastewater treatment plants in Washington don’t filter it out. So the plants inadvertently concentrate nitrogen, which is then dumped into waterways, including Puget Sound. Before modern sewage treatment, these nutrients traditionally would have been naturally spread on the land, where they more often could be absorbed into soils.

Today the Puget Sound region’s 80 sewage treatment plants dump about 26 million pounds of nitrogen into the sound each year, according to the Ecology Department. Those numbers will continue to grow as more people move to the region.

That’s a problem because nitrogen is a “nutrient” that makes plants, including algae, grow. In overabundance, nitrogen feeds harmful algal blooms that can close beaches to swimming and clamming, and sicken people and wildlife that eat contaminated shellfish. Excess nutrients are also linked to loss of eelgrass meadows that shelter fish and crabs.

Expansive Noctiluca blooms like the ones Goodwin sees in Holmes Harbor have been observed more often in recent decades, according to Christopher Krembs, the Department of Ecology’s lead oceanographer. During monthly monitoring flights over Puget Sound, Krembs in recent years has photographed the orange streaks stretching as far as the eye can see.

“We’re talking about organisms that are less than a millimeter, like the size of a hair… and yet you see them on a massive scale that you can even pick it up from a satellite,” he said. “It’s mind boggling.”

While Noctiluca isn’t harmful to people, too much of it and other types of phytoplankton that thrive on excess nitrogen can disrupt the food web, Krembs explained. Packed with ammonia, Noctiluca is unappealing fare for other creatures, yet it can overrun more nutritious, fat-filled species of algae. Similarly, jellyfish consume tiny fish, yet few creatures eat the jellies themselves. “They cannibalize the food chain,” said Krembs, reducing the amount of calories available to other marine life, including salmon and orcas, which are endangered in part because of insufficient food.

When all that algae die and break down, they cause other problems. It contributes to marine waters growing more acidic, which in turn harms oysters, barnacles, plankton and other species that both people and wildlife rely on for food.

As the algae decompose, they also suck up oxygen from the water, leaving less for other marine creatures. Levels of dissolved oxygen in these “dead zones” can fall so low that fish and other marine life suffocate, sometimes leading to massive fish kills.

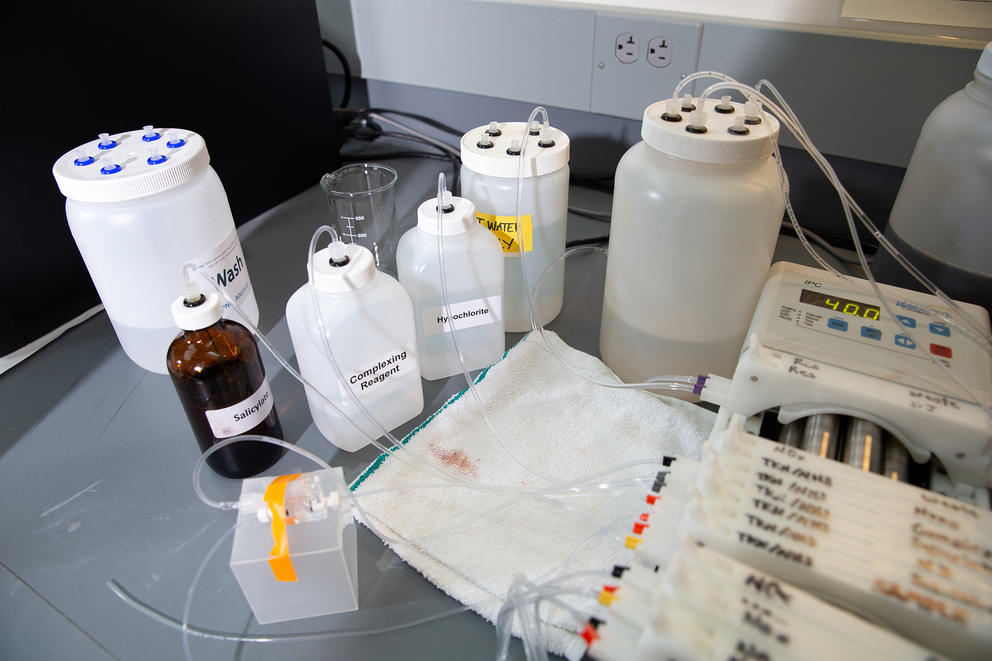

Microbe-rich water comes out of the nutrient removal basins and flows into the secondary clarifiers, where the microbes settle out and are recycled back to different parts of the treatment process. Budd Inlet is located at the southern tip of Puget Sound, and is water-quality impaired due to excess nutrients from a variety of sources, including wastewater treatment plants that discharge into Puget Sound from the north. The Budd Inlet Treatment Plant has one of the strictest permit limits for nutrient discharges in the state. (Karen Ducey/InvestigateWest)

The Clean Water Act sets standards for the amount of dissolved oxygen that must be found in marine waters. Rising temperatures resulting from climate change are expected to further drive down oxygen levels.

While some Puget Sound inlets have naturally low oxygen levels, excess nutrients from sewage are making the problem much worse. Much of Puget Sound at times suffers from low oxygen. In some recent years, inlets in the south sound and Whidbey Basin have had dangerously low oxygen for more than half of the year.

The Clean Water Act requires states to develop cleanup plans to address these “impaired” waters, a move that Washington has so far resisted. Now, after nearly two decades of studying the link between low oxygen and wastewater in Puget Sound, Washington is poised to require wastewater treatment plants to significantly cut the amount of nitrogen they release. But it won’t happen quickly. The Department of Ecology is giving itself until 2040 to meet Clean Water Act standards for oxygen levels in Puget Sound.

If all wastewater plants limited their nitrogen output from April through October, the area of Puget Sound experiencing low oxygen could be cut roughly in half. That’s according to a sophisticated computer simulation called the Salish Sea Model that Ecology has developed with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

To meet water quality standards, the state also must tackle the smaller volume of nutrients from farm runoff, leaky septic systems and other human activities near rivers and streams that flow into Puget Sound, the model found. Ecology is developing a plan, due in 2022, that will spell out how much nitrogen must be cut from all sources.

In the meantime, Ecology has launched a process to eventually reduce nitrogen from sewage treatment plants.

In early 2020 the agency announced that, for the first time, about 70 municipal wastewater treatment plants it regulates will be required to curb the amount of nitrogen they release into the sound. Currently, only one — the LOTT plant serving Lacey, Olympia, Tumwater and surrounding Thurston County — must limit its nitrogen output.

In early November, an advisory committee representing state and federal agencies, wastewater utilities, environmental groups and tribes presented Ecology with recommendations for actions that treatment plants should take. By mid-2021, Ecology plans to incorporate those recommendations into rules that govern wastewater plants discharging treated sewage into the sound.

The main goal for the first five years after the rules take effect is to not make the problem worse. Plants will be required only to “cap” the amount of nitrogen they release at current levels.

That’s against the law, argued Bell, the executive director of Northwest Environmental Advocates, the group suing the state. The Clean Water Act prohibits Ecology from permitting wastewater plants to contribute to worsening water quality, she said.

Some wastewater plant representatives on the advisory committee objected to capping their nitrogen discharges right away, saying it could prevent cities from growing, because more people means more sewage. That was one reason five of the eight plants represented rejected the committee’s recommendations to Ecology.

Over the first five years, plants also must look for low-cost tweaks to their operations that could reduce their nitrogen loads, but it’s unclear how much they can achieve through such “optimization” measures. Wastewater treatment plants are “complicated beasts,” said Clarke, the Mukilteo wastewater commissioner. “You turn a dial, and they react in ways that are not necessarily predictable.”

Environmental groups represented on the advisory committee ultimately agreed to the recommendations. “We saw a way to thread the needle,” said Alyssa Barton, policy manager of the nonprofit Puget Soundkeeper Alliance. Plants will have to limit their nitrogen releases, she said, but they also have some time to raise money for upgrades.

The two sides couldn’t agree on a timeline for meeting new nitrogen limits. Environmentalists suggested that plants make necessary upgrades within 10 years, while utilities said it will likely take at least 15 years.

That timeline frustrates Bell, whose group was not on Ecology’s advisory council. After decades of delay, “Ecology is saying, ‘Let’s kick the can down the road,’ ” she said.

Some other states already have made significant progress in tackling nutrient pollution. On Long Island Sound, which also suffers from dead zones, Connecticut pushed treatment plants to cut their nitrogen output starting in the early 1990s. By 2013, plants there had slashed the amount of nitrogen they send into the sound by 69%.

Washington state law requires the use of “all known, available and reasonable methods” to prevent water pollution, but Ecology hasn’t updated sewage treatment standards for 33 years. Northwest Environmental Advocates is suing Ecology in state court to force the department to require modern sewage treatment methods that remove nutrients, as well as other pollutants, such as drugs that pass through people’s bodies.

Ecology said that it is instead moving ahead with its plan to set limits on plants’ nitrogen emissions based on what is needed to improve Puget Sound’s oxygen levels. Not all plants, Ecology argued, will need to install the most stringent nutrient technologies.

That doesn’t give Ecology a pass on updating sewage treatment standards, Bell said. “The law is not a matter of preference,” she said. “You don’t get to choose.”

Northwest Environmental Advocates lost its initial suit but filed an appeal in May.

Costs in dispute

Fixing Puget Sound’s low oxygen levels will require major investments by King County, in particular.

The county’s three plants, serving about 1.8 million people, account for more than half of the nitrogen entering the sound from U.S. wastewater facilities, data provided by Ecology show. If just the South plant in Renton and West Point plant in Seattle reduced their nitrogen output from April through October, when low oxygen is a bigger problem, the area of the sound with dangerously low oxygen levels would be cut by nearly one quarter, the Salish Sea model predicts.

Tacoma’s Central wastewater treatment plant and Pierce County’s Chambers Creek facility round out the top five U.S. nitrogen emitters in the sound. The cost to overhaul any of these facilities to remove nitrogen could reach into the billions, according to studies out of King County and Tacoma.

A September study commissioned by King County estimated that modest nitrogen reductions at all three of its main plants could cost as little as $305 million. Meeting the most stringent standards year-round was estimated at $5.4 billion (actual cost could be from 50% less to 300% more). The West Point plant, which is surrounded by Seattle’s Discovery Park and has little room to grow, poses the most challenges. There, implementing year-round nitrogen removal would mean releasing only minimally treated sewage during construction or building a fourth major plant, the report found.

In Tacoma, capital costs to upgrade the city’s two main plants could range from $216 million to $864 million, depending on how much nitrogen is removed and for how many months of the year. That could translate into a doubling or tripling of wastewater rates, according to Dan Thompson, who manages wastewater operations at the Tacoma Environmental Services Department and sits on Ecology’s advisory committee.

Thompson and other treatment plant representatives say they want assurances that such major investments will lead to a healthier Puget Sound.

Tacoma’s leaders “are willing to pay the money if it’s going to get a result,” said Thompson. “What they really don’t want to do is pay $864 million and then find out we didn’t save a salmon or a whale.”

Ecology, too, has studied the cost of nutrient removal. A 2011 report found that implementing nitrogen removal in all plants discharging into the sound would cost between $1.5 billion and $3.6 billion in 2010 dollars, depending on how stringent the standards are and whether plants remove nitrogen only in the summer months, when low oxygen is more of a problem in the sound. Those estimates are extremely rough. Actual costs could vary from 50% below the cited figures to 100% above, Ecology said. (Also removing phosphorus, another nutrient, would bump the cost to $4.5 billion). If all plants in the state were upgraded for nitrogen removal, households could expect to pay about $11 to $23 more per month in today’s dollars, the report estimated.

In its legal battle with Northwest Environmental Advocates, Ecology cited that report as a rationale for not updating the state’s water treatment standards, calling the costs “not reasonable.”

But Ecology’s 2011 cost estimates are likely inflated, according to Mindy Roberts, who was an environmental engineer with the agency when the report was completed. That’s because the report assumed that plants would remove nitrogen from very large volumes of water, when treating only a portion of the flows might be enough to improve the sound. Other creative solutions, such as buildings that treat wastewater on site, could further reduce costs, she said.

Now director of Washington Environmental Council’s work on Puget Sound, Roberts leads the environmental caucus advising Ecology.

“I want to get to the point where we're thinking creatively and innovatively about how to accomplish the goal, instead of just saying, ‘Hell no, we're not even going to start,’ ” Roberts said.

“It's never going to get cheaper,” she said. “People are still going to be moving here. We need to move forward.”

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, a graphic misstated the amount of nitrogen being emitted by treatment facilities in Seattle and Tacoma. The graphic has been corrected.