Six years later, in a courtroom in Nelson, British Columbia, Desautel described his relationship to the area like this: “When I come up here, I’m walking with the ancestors. … It just runs chills up and down me that I can be where my ancestors were at one time, and do the things that they did.” Desautel, a member of the Arrow Lakes Band, descendants of the Sinixt, bent to work dressing the carcass: He pulled out the heart and liver, then quartered the meat.

Linda sweated up and down the hillside, a packboard heavy with a hundred pounds of elk strapped to her back, the climb slippery with frost. After loading up the truck, the two went back to camp to hang up white cloth game bags full of meat and spotted with blood. Then they drove until they had cell reception, called the game wardens and told them what they had done.

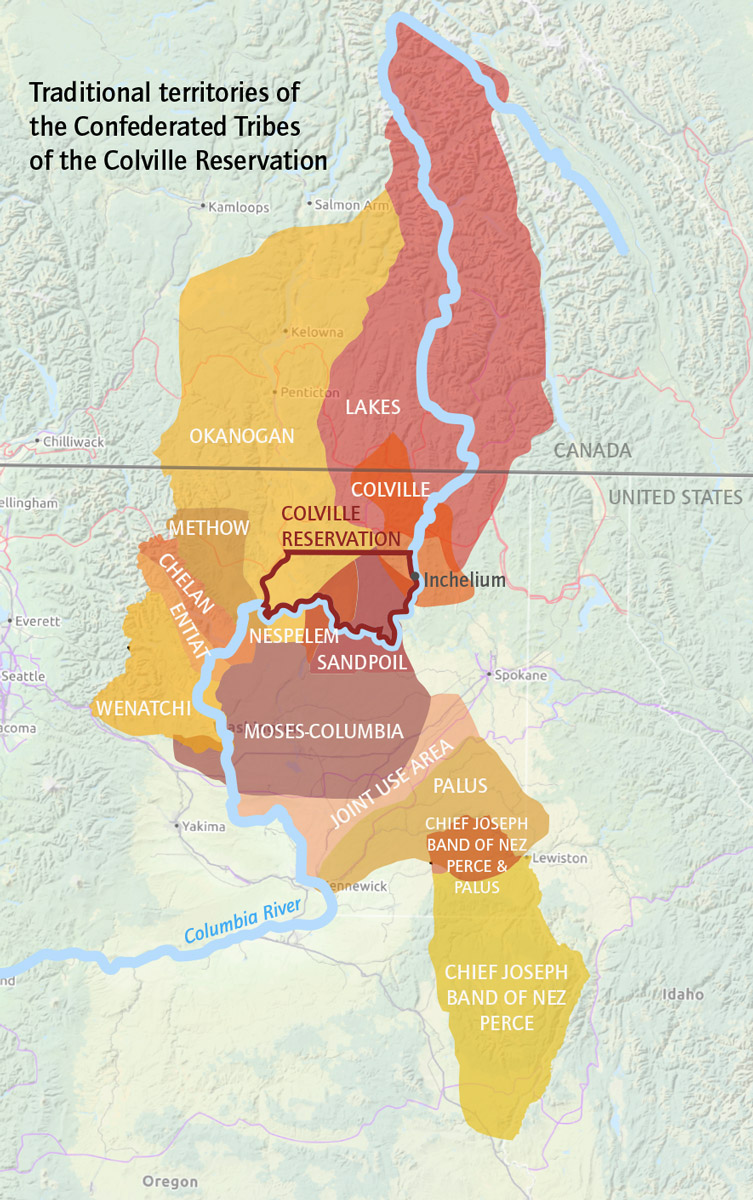

The Canadian government had declared the Arrow Lakes Band “extinct” in 1956, after the death of the last known member in Canada. But just south of the U.S.-Canada border, Arrow Lakes Band members were alive and well on the Colville Reservation in Washington state, where the Desautels live. The planning behind the hunt had been in the works for years — some would say decades — and it was a strategic attempt to force the Canadian government to recognize the Arrow Lakes Band’s right to hunt and, by extension, its tribal sovereignty.

To the Arrow Lakes Band, what Rick Desautel had done was a ceremonial hunt on land his ancestors had never ceded to the Canadian government. But to Canada, it was a crime. Although the charges eventually brought against Desautel were for hunting, at the heart of the case is something bigger — whether Canada will have to recognize the Arrow Lakes Band as a modern First Nation, acknowledging the members' right to hunt and use their traditional lands. If Desautel loses, it means the Lakes will remain, in the government’s eyes, “extinct.”

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation are composed of the Arrow Lakes Band and 11 other tribes from the region, who share a 1.4 million-acre reservation in Washington state. To go forward with the hunt, the tribal council representing the 12 bands had to agree to support it, and the court case they knew would follow. For months leading up to the 2010 hunt, tribal officials spoke with their British Columbian counterparts and with wildlife biologists, explaining their plans. The Canadians continued to insist that Arrow Lakes Band people did not “presently exist” in the province. The tribal representatives, who had expected as much, responded that they were going ahead with the hunt regardless.

Afterward, prosecutors charged Rick Desautel with hunting without a license and hunting as a nonresident of Canada. (Linda Desautel was not charged.) He pleaded not guilty.

Desautel’s case is unique because the Lakes are, as far as they know, the only First Nation to receive an explicit declaration of “extinction.” But his case, if it succeeds, means that other tribes cut off by the U.S.-Canada border with Aboriginal ties to the land could make a First Nations claim, too, even if their members aren’t Canadian residents. And that would require Canada to consult with those nations if any activity or development could impact their traditional lands. The right to own, use and control ancestral lands is enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. Canada announced its full support of the U.N. declaration in 2016, the same year Desautel’s case went to trial, as “Canada’s commitment to a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous peoples.”

During the trial, Desautel and other Arrow Lakes Band members listened while experts debated their existence in Canada. The judge ruled in favor of Desautel on March 17, 2017. But the B.C. government has since appealed twice, most recently to the Supreme Court of Canada, which has yet to decide if it will hear the case. (Editor's note: Since this story went to press, the Supreme Court of Canada has decided to take up Desautel's case.) During his preliminary hearing, Desautel recalls, an interim court lawyer told him, “You’re going to go to the Supreme Court with this case, you know, but when you do get there, you’re going to be an old, old man.” Well, Desautel laughs now, at 67, “I’m starting to believe him.”

Rick Desautel was about 10 years old the winter he went on his first deer hunt. He had been trapping small animals for years already, rambling the pinewoods and grassy meadows around his grandmother’s house in Inchelium, on the Colville Reservation, with his brother Tony. They would shoot ground squirrels and grouse with a .22-caliber Remington rifle and bring the meat home. But the deer hunt was something else — it was a rite of passage. “When that day comes, it’s mind-shaking,” Desautel said.

Since his dad had died when Rick was young, it was Tony who took him out, borrowing a .25-35 lever-action rifle from the neighbors. The pair pushed through 7 inches of snow, up to a ridge about 15 miles from home, when two mule deer jumped out about a hundred yards away. Rick aimed for the buck, but he hit the doe instead, bringing her down. “When it’s your first deer, it’s distributed with the community. None of it is ever kept,” Desautel said. “Everything that you kill is gone; deer hide, deer head, deer hooves, deer meat.” But, he added, you get the honor, “and glory.”

As a former game warden for the Colville Tribes, Desautel is used to testifying in court in cases involving poachers or drug smugglers. As in his everyday life, he’s consistent and unflappable on the stand. He has a deep knowledge of Colville reservation lands, and has spent most of his life outside: 23 years as a log cutter on top of a lifetime of trapping and hunting. He has survived half a dozen falls through ice in the winter and getting caught in a beaver trap. In 2006, while still working as a game warden, he shot down a floatplane smuggling $2 million worth of drugs onto the reservation.

As a wild animal damage control officer — his current title — Desautel removes wildlife as part of his job, “whether it be bats in your attic, elk in your field, bear on your porch.” At the direction of the tribal council, he also carries out ceremonial hunts for community events. And he’s hunted in Sinixt territory over the Canadian border since 1988.

Rick and Linda Desautel live in a tidy log cabin on 40 acres of land, with a view of a meadow and Twin Lakes in the distance. In August, golden grasses shush in the breeze while sunflowers nod along the road. Linda grew up in Omak, three mountain passes to the west, just over the bridge from the reservation’s border. Now a school custodian, she has also been a stay-at-home mom and a corrections officer. Together, the couple have fostered fawns, hawks, eagles and other wildlife. People too; even after raising six kids, they’re always providing for more.

They’ve also been partners in resistance. In 1988, Arrow Lakes Band tribal members got word that the construction of a road near Vallican, British Columbia, in Sinixt territory, was going to affect Sinixt graves. A caravan of people, including Desautels and their kids, went to Vallican to block the road. In the end, the road was built and the graves relocated to a property called the Big House, which the Arrow Lakes Band bought as a home base in their ancestral territory. But had the Arrow Lakes Band been a recognized First Nation, the result may have been different.

That was the first time Desautel had a chance to talk with a whole community of Lakes people, standing together for a purpose. At the same time, he got to see the lands that generations before him had inhabited. “It infuriated me that people would desecrate graves and stuff like this here, and pick up their bones and move them,” Desautel said. “I said, ‘OK, I’m ready for it. I’ll head up there and see what I can do to stop this.’ And that’s what I did.”

Indigenous people have long employed hunting and fishing as a form of civil disobedience. It’s been a critical method for getting courts and governments to recognize tribal nations’ legal rights to land, water and wildlife — even freedom of religion. In the 1960s and 1970s, tribal members in the Pacific Northwest, from the Nisqually Tribe to the Yurok Tribe, were beaten and arrested for salmon fishing in defiance of state laws that violated their treaty rights. Their actions resulted in multiple victories in the U.S. Supreme Court that reaffirmed their right to fish. And more recently, in 2014, Clayvin Herrera and several other Crow tribal members shot and killed three bull elk without a license off-reservation in the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming. The state charged Herrera with poaching, but a Supreme Court decision in 2019 upheld the Crow Tribe’s rights to hunt on “unoccupied lands of the United States,” in accordance with its prestatehood treaty with the federal government.

In Canada, important cases testing Indigenous rights include the 1990 decision in R v. Sparrow. In 1984, Ronald Sparrow, Musqueam, was arrested for deliberately using a fishing net twice as long as legally allowed. While lower courts found him guilty, the Supreme Court of Canada found that his ancestral right to fish was not extinguished by colonization and remained valid. “It’s definitely a very common tactic to use in Canada, which raises a lot of interesting questions about having to break the law to get certain [First Nations] rights recognized,” said Robert Hamilton, assistant professor of law at the University of Calgary.

Desautel is navigating the Canadian court system and the unique histories between Canadian federal and provincial governments and Indigenous nations. Early in Canada’s history, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, tribal nations on the eastern side of the continent signed treaties with the federal government. But as settlers pushed west, that stopped. As a result, First Nations in what is now British Columbia ceded almost no territory to Canadians. “The vast majority of the province is not covered by any treaty, and so the First Nations there have not given up their rights to the land,” said Mark Underhill, Desautel’s attorney. “We’ve been wrestling for an extraordinarily long time to deal with those rights in large part because for many, many decades, the governments of the day, both federal and provincial, simply pretended they didn’t exist — that there were no such rights.”

That began to change with First Nations land claims — when tribal nations pursue legal recognition of their right to land and resources — which set the stage for Desautel. A landmark case brought by Nisga’a Chief Frank Calder in 1973 was the first time that the Canadian courts recognized that unceded First Nation lands exist. Another big change came in 1982, when the Canadian Constitution was amended to explicitly protect Aboriginal rights. That, together with other early court cases, resulted in a modern-day treaty process as an alternative to costly court proceedings. More than 25 treaties between First Nations and the Canadian government have since been negotiated over territory, water and other resources, with more in progress. Many First Nations are not participating, however, calling instead for an overhaul of the process.

Michael Marchand, a former Colville tribal chairman and Lakes tribal member who helped plan Desautel’s hunt, said that the Arrow Lakes Band were concerned that, as other First Nations in British Columbia began to make land claims through the courts or treaties, its own claims could get edged out. But before the band could officially assert its ownership over its ancestral lands, it had to reestablish its legal presence as a First Nation.

The core of Desautel’s defense was the evidence that the Sinixt people inhabited the valleys and riversides around the Upper and Lower Arrow Lakes before Canada’s government existed. He and his legal team also demonstrated that their lifeways persisted throughout colonization, as Arrow Lakes Band members, and that they never ceded their Aboriginal rights. It’s been shown in court through Sinixt sturgeon-nose canoes, a main source of transportation before the Columbia River was dammed. It’s been shown through their place-based language and family trees. It’s been shown through the stories of Sinixt culture persisting, despite tribal members being killed by settlers and pressured out of their land, or swept off to boarding schools. It’s also been shown through Canada’s own laws: An 1896 law passed by British Columbia, for example, made it illegal for nonresident Indians to hunt. That is proof, said Underhill, of how many Indigenous people cut off by the border were continuing their way of life despite colonization.

One difficulty of the case is how few living tribal elders can speak to that history, because so many from that time have died. Still, the words they left behind remain influential. Shelly Boyd, Arrow Lakes Band facilitator and tribal member, represents Lakes interests in Canada with community members and First Nations. She points to a series of letters that had a strong impact, written by Arrow Lakes members Alex and Baptiste Christian, her husband’s ancestors, and sent to Indian Affairs agents in 1909. The Christians requested that the agents reserve lands around Brilliant, British Columbia, for the Arrow Lakes tribal members. The areas contained graves and were their home prior to settlement. Instead, the agents sold them to someone else, and the bones were eventually churned up under settlers’ plows.

“It was a really sad story,” Boyd said. But the mark that they left mattered. “They lived through a time where after all of their work and all of their sadness and all of their pain, they had to leave … but those letters that they wrote, they helped us win this case.”

Desautel is matter-of-fact about the lawsuit, as he is generally about doing what needs to be done. The actual elk hunt itself was routine, much like the hundred or so hunts that came before it. When he turned himself in to the game wardens, he knew they were just doing their jobs.

“If I let [the charges] pass, it’s going to go on to the next generation,” Desautel said. “I’m gonna throw out an anchor now. I mean, if it doesn’t hold and I go dragging on through life, my daughter or my granddaughter can come along later on and say, ‘Look here, my grandfather was doing this here. He was up here. He was doing this.’ ”

If the Supreme Court hears the case and rules against Desautel, it would be the final say — period. “If we lose, we’re out of the game, we’re extinct,” Boyd said. Though 10 years younger than Desautel, Boyd knows him from growing up in Inchelium, where their grandmothers were best friends. She sees, and feels herself, what the land means to him. “He is risking something he loves very much.”

Regardless of the final outcome, Desautel will continue hunting in his ancestral lands in the years to come. If he loses, he shrugged, “They’re going to have to put handcuffs on me then.”

The trial progressed sporadically over four months. The early mornings and long days away from home wore Rick and Linda out, and court proceedings were often mind-numbingly boring; Linda joked that the prosecutors sounded like Charlie Brown’s teacher. In essence, the prosecution argued that the Sinixt people voluntarily left their lands, moving south to become farmers and abandoning their traditional lifeways, thus giving up their rights as a First Nation.

About halfway through the trial, Dorothy Kennedy, a leading ethnographer who documented Sinixt histories in the ’70s and ’80s, took the stand as an expert witness for the government. Despite her past work for the tribe and her conversations with Arrow Lakes elders, Kennedy did not consider the Arrow Lakes Band a First Nation. Nor did she believe that the Sinixt experienced racism from settlers. Instead, she testified about “isolated incidents” of harassment that went “both ways” — because, she said, the Arrow Lakes were Americans in Canada, not because they were Indigenous. In the report she submitted to the court, she wrote that instead of “meekly fleeing settlement … they enthusiastically took up a different lifestyle south of the border.” To Desautel and his team, it felt like a betrayal.

When Mark Underhill was hired by the Colville Tribe to take on Desautel’s case, multiple senior attorneys told him that they’d never win. But nearly four months after the trial finished, the judge found that Desautel was within his rights as an Aboriginal person to hunt within his ancestral territory. The courtroom, filled with Arrow Lakes tribal members and extended family, erupted in cheers and applause.

So far, after two appeals, other judges have agreed with the first ruling. After the most recent one in March this year, from his office in Vancouver, British Columbia, Underhill called Rick and Linda on the phone at their home in Inchelium and read the judge’s statement aloud on speakerphone. “[The judge] said some amazing things,” Linda said. “She made me cry.”

As long as the lower court ruling stands, the Canadian government now has a duty to consult with the Arrow Lakes Band concerning activities like logging and hydroelectric developments, or anything else that might impact their rights in the area. But there are also more intangible benefits of “Desautel,” as the decision has come to be known. “There’s some kind of indescribable freedom to it,” said Boyd. “I grew up knowing I was declared extinct in Canada. As an 8-year-old girl, it’s like, what? Dinosaurs are extinct. It is still really inconvenient for us to exist.”

Despite the resolute language of the past three judges, the Desautels aren’t assuming they’ll ultimatelhy win. “[We’ve] never felt totally confident,” Linda said. “You’re dealing with the government. I don’t care who you are and what country you’re in. Never feel confident of your government, especially Native people. We know.” Still — Rick wanted them to take up the case, to have Canada’s highest court affirm his rights.

As Arrow Lakes Band facilitator, Boyd has her sights set on what comes next for the tribe. They’ve reintroduced salmon to the upper Columbia River for the first time in almost 80 years and resumed canoe journeys using their traditional sturgeon-nosed canoes. Next, they’re planning to reestablish the Sinixt language, nsyilxcen, in their territory. And every fall, Desautel will continue to cross the northern border to hunt.

The hillside in British Columbia where Desautel shot the cow elk is overgrown now, nine years later — 20-foot-tall white pine, tamarack and western hemlock trees crowd out the view of Slocan Valley below. In late September, not far from there, he explored the steep draws and thick forests of Sinixt lands for signs of elk. While scouting for game with Desautel, the place comes alive even without any wildlife in sight. Faint prints of a bear cub crossing a road. Scat of a bigger bear from the morning, bright with berries. Torn tree bark from where an elk rubbed its antlers two weeks before. Alder saplings stripped of their leaves, a snack for a meandering moose. After a life lived outside, Desautel can read the forest’s early autumn activity like a book he’s paged through a hundred times before.

Desautel doesn’t usually hunt until later in October, when the days are colder. For now, he’s exploring — glassing the countryside with his binoculars, occasionally bugling for elk, searching for a spot that “looks elk-y.” As he hiked back down to his red Toyota Tacoma, the shoulder-high fireweed released its seed tufts like a cloudburst, swirling in his wake. As he drove north, cresting over Strawberry Summit, Desautel looked out at the expanse before him. “This country is so vast,” he said with a note of pride. “I’ve only checked out 1% of 1%, and I’ve got hunting rights as far as the eye can see.”

This story was originally published at High Country News on Oct. 28, 2019.