The Pulitzer Prize-winning musician was speaking to Crosscut about the wider implications of planned cuts to local music programs in public schools.

In March, as a result of budget cuts affecting schools throughout the region, administrators at Washington Middle School (WMS) in the Central District elected to cut their award-winning jazz program.

The decision was quickly opposed by WMS students and parents, who testified in support of the program before administrators at the Seattle Schools Board Meeting on April 4. Alarm regarding the proposed cut resonated across the region, as other schools like Mountlake Terrace High School and districts including Shoreline and Olympia are weighing similar reductions to their music programs.

Word of the hit to WMS’s program traveled across the country and reached Marsalis, the revered musician, jazz educator and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City.

Marsalis knows well that jazz education imparts benefits beyond notes and rhythm. “Improvisation gives you confidence in your individuality. Swing teaches you to respect and nurture common ground. And the blues teaches you optimism,” the music legend told Crosscut.

“You’ve heard of the [teen] mental health crisis?” he continued. “We need to be increasing general music education for [kids] so that they can develop the taste to make intelligent choices and counterbalance the commercialism that’s just ruining the quality of their internal life.”

Aside from giving kids purpose, joy and a social outlet away from their cell phones, the WMS jazz program — also known as the Junior Husky Jazz Band — has long been foundational to Seattle’s national reputation as an incubator for professional jazz talent.

WMS jazz is award-winning in its own right, but also a pipeline for Garfield High School’s renowned jazz program, which has qualified 18 times for the prestigious Essentially Ellington Competition and won top honors four times at the national contest.

“Seattle’s are the finest jazz programs in the country, with Garfield, Roosevelt and other significant programs leading the way,” said Marsalis, who produces the Essentially Ellington High School Jazz Band Competition & Festival through his role at Jazz at Lincoln Center.

This year, Garfield High School, Roosevelt High School and Bothell High School are three of only 15 finalists at the 28th annual Essentially Ellington competition, set for May 11-13.

The program at WMS has launched the careers of Grammy-nominated jazz and hip hop artist Kassa Overall; pianist and composer Carmen Staaf; flutist, composer and Berklee School of Music professor Anne Drummond; and trumpeter Riley Mulherkar, Jazz at Lincoln Center’s 2020 Emerging Artist, among others.

Many of these WMS alumni spoke with Crosscut and expressed devastation and concern at the potential loss of a program so integral in their development as musicians — and as human beings.

Riley Mulherkar (second from left) and Willem de Koch (far right), both alums of the Washington Middle School and Garfield High School jazz programs, went on to found New York-based brass quartet the Westerlies. Other members of the award-winning group are Chloe Rowlands (left) and Andy Clausen (third from left), who played in Roosevelt High School’s jazz band. (Courtesy of the Westerlies)

“That [program] was an extremely impactful, life-changing experience,” said Overall, who attended WMS from 1995 to 1998. “What we learned in [jazz] classes really affected our characters. It taught us how to be mature, responsible and disciplined. I don’t think that I would be the person I am today if I didn’t have that early on.”

Mulherkar, who graduated from WMS in 2006 and later co-founded the award-winning jazz collective The Westerlies, feels similarly: “The bottom line is that I basically owe my entire career and passion to the jazz programs at Washington Middle School and Garfield High School,” he said. “And the bigger picture to me is the importance of jazz as an opportunity to learn all these lessons that apply to everyone, even if they don’t go on to become a professional musician, like how to listen and improvise.”

He echoed the sentiment that jazz education has larger implications: “In terms of this country’s cultural heritage, jazz in the schools gives you an understanding of music, but also ... a lens through which to understand the bigger picture of what’s going on in every classroom,” Mulherkar said.

WMS’ celebrated jazz program began to flourish in the 1970s, when Seattle Public Schools specifically sought to hire minority music teachers from HBCUs (historically Black colleges and universities) across the country. In 1976, SPS recruited Robert Knatt from Louisiana to lead the WMS jazz band.

Among other recognitions, under Knatt the students earned consecutive wins each year from 1994 to 2002 at the University of Idaho’s Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival.

“Being there [was a major] contributor to why I’m actually a professional jazz musician now, and that’s not overstating it,” said New York-based pianist and composer Carmen Staaf, who played in the WMS jazz band during that prizewinning period. “[We were] winning awards and traveling, and I really felt like, OK, this is the beginning of ... a whole path ahead.”

Over the past two decades, there has been a lot of turnover in the WMS jazz program. After Knatt’s retirement in 2008, it continued to flourish under the careful eye of Kelly Clingan, who now works as educational director for Seattle JazzED, a local jazz-education nonprofit. She moved on from WMS in 2016, at which point Jared Sessink took over.

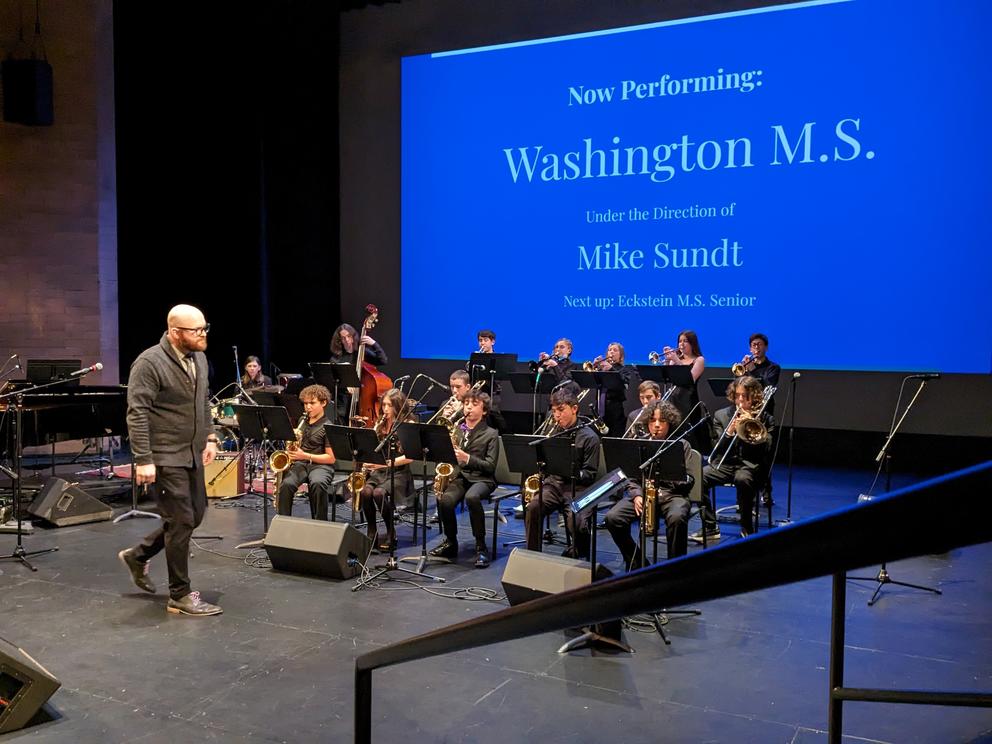

In 2019, following the retirement of Clarence Acox, another HBCU-recruited teacher and Garfield’s band director for more than 40 years, Sessink moved on to Garfield and Michigan-bred Mike Sundt became director of bands at WMS.

Though the program has decreased in size due to the pandemic (which presented myriad challenges for K-12 music programs around the country), Sundt’s reception has been warm.

Many recent students, including 14-year-old Cameron Rose, now a freshman in the jazz band at Garfield, said jazz was her “favorite class” at WMS and that she’s “worried and sad” that other kids won’t have the chance to experience it.

Current students and alumni also noted that the jazz program has provided them with an education in essential American history and a tether to the cultural legacy of the Central District, Seattle’s historically Black neighborhood, where groundbreaking jazz artists like Ray Charles, Quincy Jones and Ernestine Anderson launched their careers. Enrollment at WMS is 80% students of color; the WMS jazz band is just under 27% students of color.

“Jazz is important to my culture [and] heritage as a Black young man,” said 12-year-old WMS student Saire Williams during his testimony at the April 4 school board meeting. “And SPS has said that they’re committed to pursuing educational justice for Black male students. Reducing funding for our school, cutting our band program does not provide for the needs of other students, and it’s not educational justice for Black students.”

The local fight to keep jazz programs alive comes at a political moment when lawmakers around the country are attempting to pass legislation that could prevent the teaching of Black history and other allegedly “divisive” issues in schools. According to a recent report from PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for freedom of expression, 36 states have introduced more than 137 bills in the past year that would limit what schools can teach about race.

“[Jazz] is one of the few opportunities that we have in the educational system to celebrate Black culture and Black arts, and to elevate it to the stature of recognition that it deserves,” said WMS alum Tatum Greenblatt, a Juilliard-educated jazz trumpeter who plays on Broadway and has toured with groups like Blood, Sweat and Tears.

WMS’s jazz program was originally put in jeopardy earlier this year, when, facing a $131 million budget shortfall, SPS informed administrators at WMS that they would have to eliminate one of 20 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions.

In response, WMS administration began conversations to determine how to accommodate the budget shortfall. After debating options, the administration put the reduction of FTE positions up for a staff vote. (Per the teachers' union contract, any decision-making about the school budget must pass with a two-thirds vote from union-represented staff.) Unsurprisingly, staff did not vote to approve the FTE reduction.

But WMS sources say the vote was moot, since the FTE reduction mandate from SPS was non-negotiable. A few days later, on March 3, Mike Sundt learned from the administration that his FTE position was the one recommended for the cut. The reduction from two full-time music instructors to one would also slash the number of classes in the music department from 10 to five.

“There wasn't really an alternative because ... obviously, you have to fill your positions in math, science, language arts, social studies,” Sundt said. “What we were left with was enough funding for four teachers to teach electives, and we currently have five. It just happened to be that [a] music [position] was the one that was cut.”

The district budget allocation is not yet final, thus the decision to eliminate the second music FTE position and reduce the program’s class offerings is not official. According to an SPS Budget Information Session on March 20, the school district’s budget — including the funds allocated to each school — will be finalized by May, reviewed and voted on by the school board by July, and submitted to the state in August.

If this decision does stand, current director of orchestra and choir Luke Hartley, a first-year teacher, will next year be responsible for teaching all five music classes — choir, orchestra, and band specialties. (Sundt cannot legally teach all three of these subject areas because he does not hold a teaching certification in choir.)

In hopes of reversing the decision, WMS students, along with parent volunteers in the Friends of WMS, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that works to improve access to music education at WMS, are planning a student-led march sometime after spring break, which ends April 14.

The Seattle School District has declined to comment on what’s happening at WMS, but released a statement expressing, in part, that “budget adjustments are incredibly difficult. However, the commitment to our excellent music programs is unwavering. High-quality music instruction remains a priority and will continue at WMS.”

Prior to the news of his displacement, Sundt had every intention of continuing to grow the band program, with attention to diversity and equity, by helping students get access to instruments and working to make kids of all backgrounds feel comfortable in the band room. With a background in and passion for jazz education, he had also hoped to gradually engage more students in the band programs to grow the jazz ensembles back to what they were under Knatt.

“I see jazz education as massively important for [middle schoolers] because you have to work together to make something beautiful, and that takes a lot of work. You have to be able to have conversations with your peers, you have to learn how to listen to people and respond to them musically,” said Sundt. “It’s important ... particularly at this age, because this is when you start to decide just what kind of person you will be.”

This story has been updated to clarify the process preceding the recommendation to eliminate Mike Sundt's position. The WMS Building Leadership Team did not recommend this course of action.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.