The pavilion was designed by Seattle-born architect Minoru Yamasaki (1912-1968), who designed the World Trade Center in New York City around the same time as the World’s Fair. For the Science Center, he created a cluster of concrete buildings encircling a courtyard with two large reflecting pools and walkways topped with a quintet of 100-foot-tall, gothic-like decorative “space arches.” The quad was to be a place for reflection, a cloistered oasis away from the hubbub of the fair.

In the fall of 1962, after the Fair closed, the Seattle landmark building became home to the Pacific Science Center, a nonprofit science museum located on the southern edge of the Seattle Center grounds.

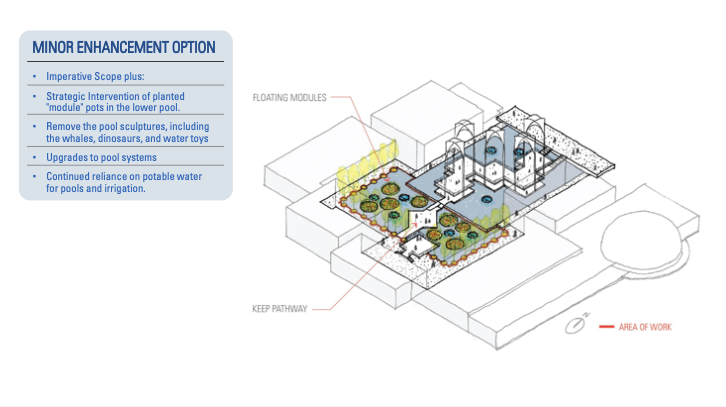

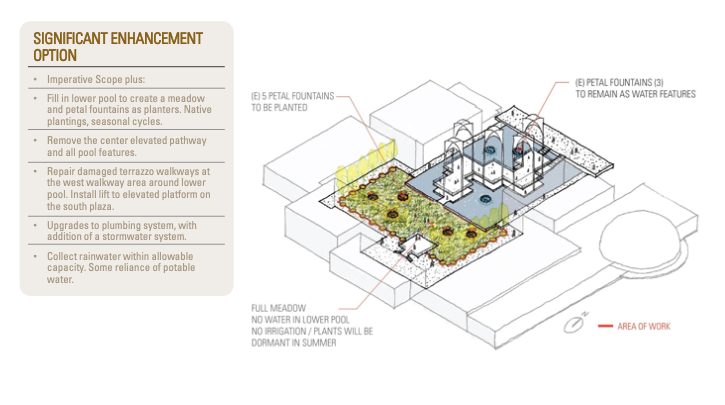

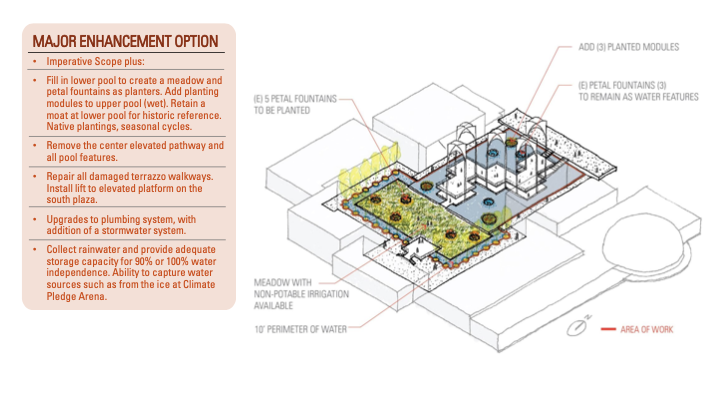

Sixty years on, the Pacific Science Center has announced plans to transform the courtyard into an “urban ecosystem” that integrates water, plants and animals. This could mean anything from a standard renovation to siting planters in the iconic pools to transforming the pools into a meadow filled with native plants and a “rainwater garden” to attract pollinators, songbirds and butterflies.

Because PacSci’s building is a City of Seattle landmark, the organization must make its case to the City’s Landmarks Preservation Board, which has to give its blessing for any changes to the facility’s exterior (and much of its interior). PacSci is presenting its vision and initial scope of the plan to the board on Wednesday, Feb. 15. Wednesday’s meeting is informal, in that there will be no action taken by the Board. This presentation offers the Board, and the public, a chance to chime in with questions and comments.

The plans, outlined in a 35-slide presentation, are still in the conceptual stages, but what’s sure is that the changes would include a much-needed $17 million renovation of the water basins, which would essentially keep things as is. Any “enhanced options” would include the removal of the pool’s giant (non-original) plastic dinosaur sculptures and interactive water cannons. PacSci plans to raise funds for this via a future campaign. Any additional significant changes (like the meadow option) would cost an additional $15 to 20 million, Daugherty said.

“While we’re doing that [renovation] work, instead of spending a lot of money to make it stay the way it is, we have a vision … to bring the courtyard to life,” PacSci’s President and CEO Will Daugherty said. “Keep the footprint as it is, maintain water in those ponds, but add living things: native plants that will attract native pollinators and demonstrate what a natural ecosystem is like in this region,” he said.

“What we have in mind is something that will be even more engaging, even more valuable, even more consistent with our mission and guiding principles,” Daugherty added. “And even more consistent with the ideals of Yamasaki and the ideals of the initial foundation of the United States science exhibit and Pacific Science Center.”

Daugherty said the plans aren’t final and that refinements will be made “based on all kinds of dialogue with community members,” including the Landmarks Board, but that he’s already gotten positive feedback. He also said the nonprofit plans to work with members of local Indigenous communities to shape the design, development, construction and, eventually, related educational programming of the new courtyard.

The proposed renovations are not unusual — upgrades to crumbling facilities are a typical part of the life cycle of landmarked buildings — but the other plans PacSci has put forth are poised to be more controversial.

The meadow proposal has already ruffled feathers among preservation advocates. “There is a huge amount of concern … about this proposal,” said Jeffrey Karl Ochsner, architecture professor at the University of Washington and a preservation advocate. “There's clearly going to be pushback in the Pacific Northwest, not just in Seattle, but in the region.”

Ochsner doesn’t take issue with maintenance and repairs, but transforming the pool into a meadow, he said, goes too far. And, he said, it won’t fly with the Landmarks Board, which has to follow the U.S. Department of the Interior’s standards for preservation. “I just don't think it's possible. So I doubt that the proposal is going to go forward.”

The Pacific Science Center became a landmark in 2010 after a unanimous vote by the Landmarks Preservation Board. It’s one of just a handful of Seattle buildings that meet all six designation criteria for landmarks (the others also include other World’s Fair buildings like the Space Needle and the Washington State Coliseum, which became the KeyArena and is now Climate Pledge Arena).

In the designation process, the landmarks board placed “controls” on the building’s exterior and much of the interior, including the entry towers, walkways and pools, but not including the non-original water features and dino sculptures. Changes can sometimes be made to landmarked buildings, but only if they aren't permanent or don't significantly alter the protected features.

Eugenia Woo of the preservation advocacy group Historic Seattle said that she couldn’t say whether her organization could get behind the “minor enhancement” option PacSci has put forth in its plan (which includes the installation of planters), and that she needed more details. But a meadow: That’s a clear no, Woo said. “It’s a completely different thing … from a water feature,” she said. “It really changes the character of the whole place.”

“The interplay between the water feature and the buildings and the arches, it’s integral to the whole site,” Woo added. “To have that altered so drastically, to me was a shock.”

To Woo and Ochsner, taking away the water is taking away what made the courtyard, and the design at large, a beacon of reflection. “You have the sound of the fountains, you have the reflections during the day of the water, and at night, the reflections from the illumination, you have relative quiet compared to the rest of the fairgrounds … you’re really in a space of reflection,” Ochsner said of Yamasaki’s intention.

PacSci’s proposal comes as the organization, and the campus at large, is at a turning point. On the heels of a successful 60th anniversary year and nearly three pandemic years, Seattle Center’s longtime director, Robert Nellams, retired this month. (Marshall Foster, the Director of the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects, will serve as interim director of Seattle Center while the search for a permanent director is underway.)

The Seattle Opera tore down Mercer Arena to build its new 105,000-square-foot facility, which opened in 2018. Climate Pledge Arena opened in the fall of 2021 after a years-long, $1.15 billion redevelopment. Meanwhile, local arts organizations say the construction of a light rail extension coming to the campus in 2037 could displace them.

PacSci is also at a crossroads. Director and CEO Daugherty sketched the plan to transform the courtyard as a bid to attract and stay relevant with a wider and more diverse audience and help create financial sustainability for the organization. Tax forms submitted to the IRS show that in the decade preceding the pandemic, the nonprofit ended most years in the red.

“A courtyard that provides a richer experience … will be a more attractive place to visit, will be a place that people want to attend, be members [of)], want to support,” Daugherty said. “This investment will strengthen our economic sustainability [and] will make Seattle Center a more attractive place to visit.” (Seattle Center did not respond to an interview request.)

The pavilion was originally built to house the largest science exhibit ever assembled by the federal government at the time. Yamasaki (who later also devised the Rainier Bank Tower, the IBM building in Seattle and New York’s World Trade Center) designed the pavilion’s five buildings as windowless warehouses — decorated with a wishbone concrete pattern reminiscent of gothic arches — where visitors could focus on the exhibits inside.

To walk into the courtyard was to be flooded with natural light. Yamasaki was sometimes called a “romantic modernist” because he, in his own words, denounced “the dogma of rectangles.”

“My premise is that delight and reflection are ingredients which must be added,” he said in a 1963 Time cover story (which featured a drawing of the pools), and explained how his designs sought an element of surprise: “ ... the experience of moving from a barren street through a narrow opening in a high wall to find a quiet court with a lovely garden and still water; or to tiptoe through the mystery and dimness of a Buddhist temple and come upon a court of raked white gravel dazzling in the sunlight; or to walk a narrow street in Rome and suddenly face an open square with graceful splashing fountains.”

Maintenance issues have plagued PacSci’s pools for years. In 2011 the pools were refurbished and resealed, but the issues persist. “We have been holding together through patchwork,” Daugherty said, “and that is not sustainable. There’s a risk of catastrophic failure that would make it impossible to continue with those ponds as they are.”

But the new plans are also a way for PacSci to be more ecologically sustainable: right now, the pools are filled (and replenished) with potable water. According to PacSci, the ponds lose on average 71,000 gallons of water per day due to leakage and evaporation. The enhanced plans PacSci is proposing would instead reuse captured rainwater.

It’s also a way to honor the history — and the future — of the land and its ecological systems, Daugherty said.

“When we think about historical preservation, it's important to look back more than 60 years,” Daugherty said. “600 years ago, this land belonged to Native communities. We don’t intend to tear the place down. But we want to engage those Native communities and think: ‘How do we showcase the long arc of history here, how natural systems have evolved over decades, centuries and millennia, and where those natural systems are going from here?’”

What would Yamasaki have thought about all this? It’s hard to say (his daughter did not respond to an interview request), but it's clear that Yamasaki was no preservationist. When he designed the IBM Building and the Rainier Tower for downtown Seattle, he didn't mind that raising his towers would mean razing historic structures.

At the time, some advocates hoped the Seattle Landmarks Preservation Board would be a weapon against his high-rise plans — but they were defeated. Yamasaki's towers went up, and are still standing.

This story has been updated to reflect that all the “enhanced options” PacSci is exploring include removal of the pool’s plastic dinosaur sculptures and interactive water toys, but that a renovation would keep things essentially as-is.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.