THE THIRD, MEANING: ESTAR(SER) Installs the Frye Collection (through Oct. 15, 2023) is all about attention — specifically, the attention we pay to art, individually and as humans generally. During the above encounter, the mother’s attention was on her daughter, the daughter’s attention was on social media, and my attention was on their dispute. Was anybody engaging with the art? These are the kinds of questions the exhibit is built on, and also, “What do artworks want from us? And what do we want from them?”

Luckily, the abstract thinking behind the show results in a thoroughly enjoyable experience for the viewer. Pay no attention to the obfuscating exhibit title! Instead, feast your eyes — and attention — on this clever and surprising restaging of works from the museum’s holdings.

Organized by the research collective ESTAR(SER), led by D. Graham Burnett of Princeton and Joanna Fiduccia of Yale, the show arranges pieces from a long historical timeline into groups of three. (The concept hinges on a throuple that emerges in art viewing: the work, the watcher and the attention.) Figuring out what connects each triad of artworks gives the satisfaction of completing a little visual puzzle. This makes it a great show for young kids, as well.

In one trio, it’s an angular slash of red, as seen in a portrait of a German count from 1873, a Russian propaganda poster from 1918 and an Impressionistic painting of bishops from 1962. In another grouping, all heads are turned to show the backs of necks. In yet another, Alison Bremner’s striking 2017 wall piece featuring a deer hide painted with pink and black latex shares a wall with a modernist rural landscape painting by Thomas Hart Benton (“Chilmark,” 1922) and Heinrich von Zügel’s impressionistic portrait of three cows (1912). Can you see the connection?

Sometimes the triads are connected by the objects depicted (mirrors, birds, windows), sometimes it’s a shape or a vibe. Often I found more than one thing linking the triad. But mostly I found that I was paying close attention, my brain enlivened by thinking about the art in different ways and new contexts.

Fresh attention to art arrangement is also the inspiration behind the new show at Seattle Art Museum. American Art: The Stories We Carry (ongoing) marks the first time in 15 years that SAM has reinstalled its American art collection. Previously a room awash in ornately framed landscapes and portraits by American artists of European descent, the gallery is now alive with new neighbors: works by African American, Native American, Asian American and Latino artists.

The new arrangement allows us to experience reverberations between the abstract paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe and the sculpture of George Tsutakawa; between Marie Watt’s towering stack of Native woolen blankets and the colorful kimonos Roger Shimomura includes in a painting depicting the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II.

SAM engaged in a two-year process to reconfigure the collection, with museum curators working in collaboration with community advisors and regional artists, including Inye Wokoma and Wendy Red Star. They investigated the questions: What is American art? And whose “American” stories are told?

Having previously seen the Frye show, my eyes were eager to make connections in threes. I found plenty, including a striking section that includes a huge portrait by Kehinde Wiley, a tintype photo of a Lummi violinist by Will Wilson and a turn-of-the-century cast-bronze sculpture of an “Indian Warrior” by Alexander Phimister Proctor. Each holds a long straight object: a rod, a violin bow and a spear. Each prompts thoughts about who is portrayed in art and how.

As you walk around the spaces — experiencing works from Gee’s Bend quilters to Pacific Northwest modernist painters — you may notice a repeated audio loop. It’s a recorded welcome in the Coast Salish language of Lushootseed, a reminder to think deeper about the origins of America.

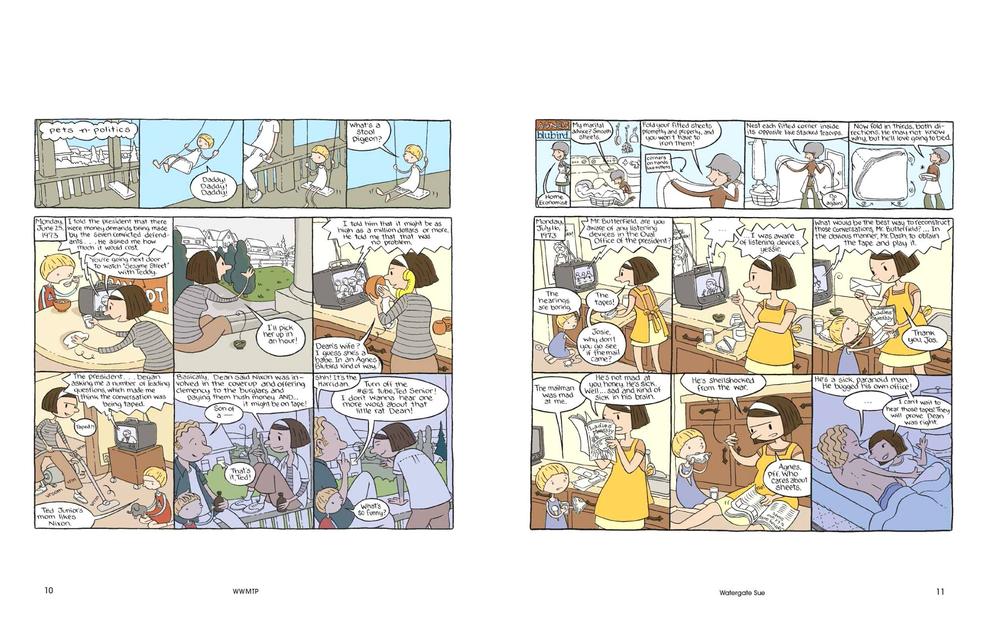

American stories crash together, too, in a lovely new book by longtime Seattle comic artist Megan Kelso. Published by local comics legend Fantagraphics, Who Will Make the Pancakes features five of Kelso’s long-form comic stories. Reading like graphic novellas, the stories range from realistic (a coming-of-age rock-climbing tale) to fantastical (cats trained in Downton Abbey-style service skills).

In one of my favorites, “Watergate Sue” (originally published serially in The New York Times Magazine), multiple timelines share the pages to tell a family story. A young married woman in the 1970s becomes increasingly enraged at the Nixon hearings — continually being broadcast from her tiny TV — yet she can’t seem to pull away. Kelso artfully shows how the media of the time (including advice columns aimed at helping housewives do chores better) demanded attention, filtering into and impacting daily life. Meanwhile, the woman’s future daughter is dealing with motherhood challenges of her own.

Kelso will talk about the book at the Seattle Public Library (Nov. 6, 1-3 p.m.; also streaming) in conjunction with the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival happening this weekend (Nov. 5, 11 a.m.-6 p.m. at Seattle Center’s Fisher Pavilion): another creative mashup of stories, timelines and art deserving of your full attention.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.