“The Seasons’ Canon” (through Nov. 13 at Pacific Northwest Ballet, on a mixed bill with works by Dwight Rhoden and George Balanchine) is the latest work by unparalleled Vancouver, B.C. choreographer Crystal Pite, and it’s the most stunning performance I’ve seen all year.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

There are four more chances to see it and I truly can’t recommend it highly enough. With music set to Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, “re-imagined” by British composer Max Richter and played live by the PNB orchestra, the contemporary piece features more than 50 dancers moving together to illuminate the vast churnings of the universe.

Performing massive undulations, ripples and rolls, the dancers evoke the natural processes that have astounded humans ever since we first showed up: ocean waves, spring’s sudden floral burst, leaves turning color and falling in unison. It’s like watching a murmuration of starlings — a colony of creatures moving together in some shared intelligence.

On opening night, people sitting around me gasped and whispered “ohh” at various times, as the shapes Pite created sparked both surprise and limbic recognition. With all its careful synchronization, there’s real emotion here too. I found myself tearing up at the soft brush with the sublime.

Pite’s choreography often brings animals to mind (a la the buzzing swarm in “Emergence,” also in the PNB repertoire), and in “Canon” we see crab-like scuttling, spidery elbows, birdlike head flicks and other signature moves in her startling dance vocabulary.

But there’s deep humanity as well, in the way the dancers lift, push, pull and support each other — I was often reminded of the closely pressed soldiers depicted in the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial. In one section highlighting Amanda Morgan (who just became PNB’s first-ever Black woman soloist), dancers pivot on an axis while gently holding each other’s faces from behind.

At a PNB studio run-through I attended a few days after the opening, rehearsal director Anne Dabrowski passed along some notes from Pite (who had left town after the premiere). In one section, the choreographer asked the dancers to stretch their necks back further, as if we could “see your throats from space.” That’s the interstellar perspective Pite brings to dance — a hyper-awareness of our planet making its inevitable turn.

Immersing yourself in art that reflects the larger forces of nature is a pretty solid way to come down from election jitters. Thankfully there are several more ways to do so this weekend.

The ebb and flow of bodies in Pite’s dance piece has a visual parallel a few blocks away, at MadArt Studio in South Lake Union. Back in August, I wrote about the very beginnings of Alison Stigora’s log-scale installation, Salvage. It’s now complete (up through Nov. 23) and serves as a marvelous midday meditation. The giant pieces of driftwood plucked from Puget Sound waters are arranged in a tall wave that looks frozen in time. Step inside, sit down on one of the lower logs, and disappear into the smell of wood and the subwoofer soundtrack, sourced from underwater glubs and low tones.

The magic of the natural world is also heralded at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, which is currently showing a retrospective of work by longtime Seattle glass artist Ginny Ruffner. In addition to many intricately sculpted works, What if? (through Feb. 15, 2023) includes an eye-catching installation in the building’s two-story front windows inspired by the glow and flow of the aurora borealis. Called “Project Aurora,” the 20-by-10-foot sculpture is made of hanging bars of led bulbs.

Ruffner brought in Ed Fries, an ex-Microsoft programmer who led the team that built the first Xbox, to construct her vision. He wired in 34,560 one-millimeter individually addressable LEDs, and programmed the GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) to create the shifting display. I’m not going to pretend to understand the technical details, but apparently the “neural network” is “learning” how to replicate the aurora borealis, based on images it’s been fed of the real thing. That means the display is always different, never repeating, while casting its mysterious luminescence into the distance.

If rays of colored light are sounding really good (hello, 4:38 p.m. sunset), head to the Pilchuck Glass School campus in Stanwood, where this weekend Seattle neon artist Kelsey Fernkopf has installed his minimalist, geometric neon sculptures in the woods. Light the Forest (Nov. 11 - 13, 3:30 - 6:30 p.m.) promises portals that might just take us to another world.

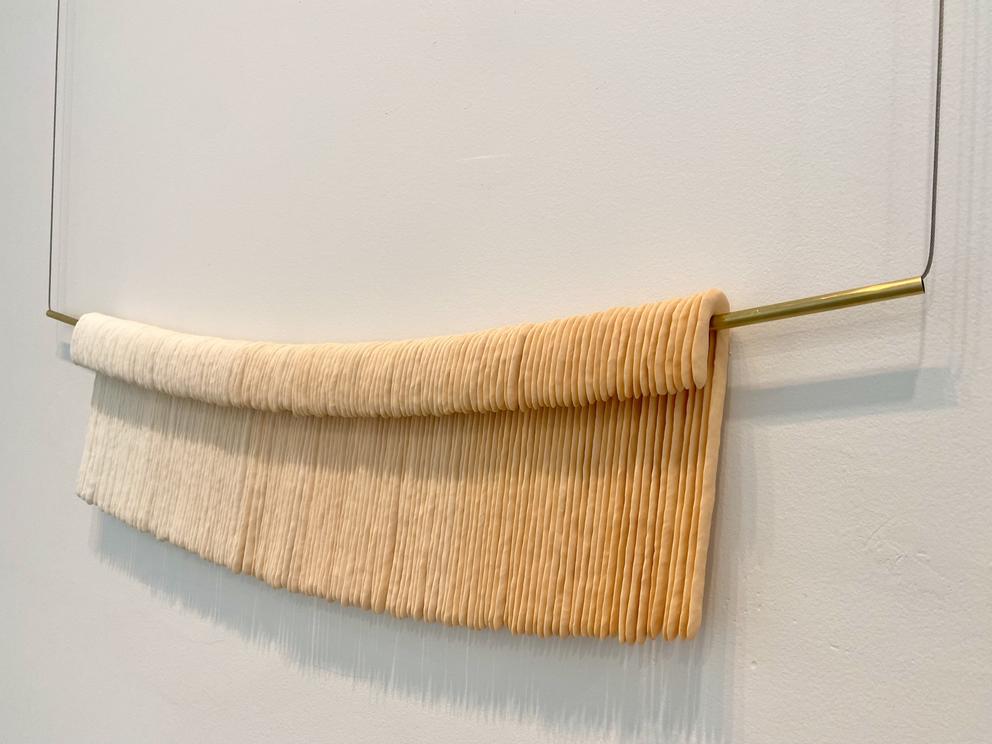

The mysteries of light are also being explored at Vestibule gallery in Ballard, where local ceramic artist Amanda Salov has a new show, Borrowed Light (through Nov. 19; artist talk Nov. 19, 4-5 p.m.). The many-windowed storefront space is currently filled with her delicate porcelain installations, featuring repeated rows of small ceramic shapes that appear soft as fabric. Thanks to Salov’s precise introduction of tint to clay, these ombré objects shift ever so slightly in color from one repeated form to the next, creating a tonal ripple that reminded me of a certain spectacular section in Crystal Pite’s piece.

In her artist statement, Salov says she finds comfort in natural phenomena that are both constant and ever-changing, such as the sea and sky. “Light and color in the atmosphere,” she writes, “are always changing, whether we can pay attention or not.” She takes this as a metaphor — a way to stay grounded amid major transitions (political, personal, seasonal), to remain anchored among waves of change.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.