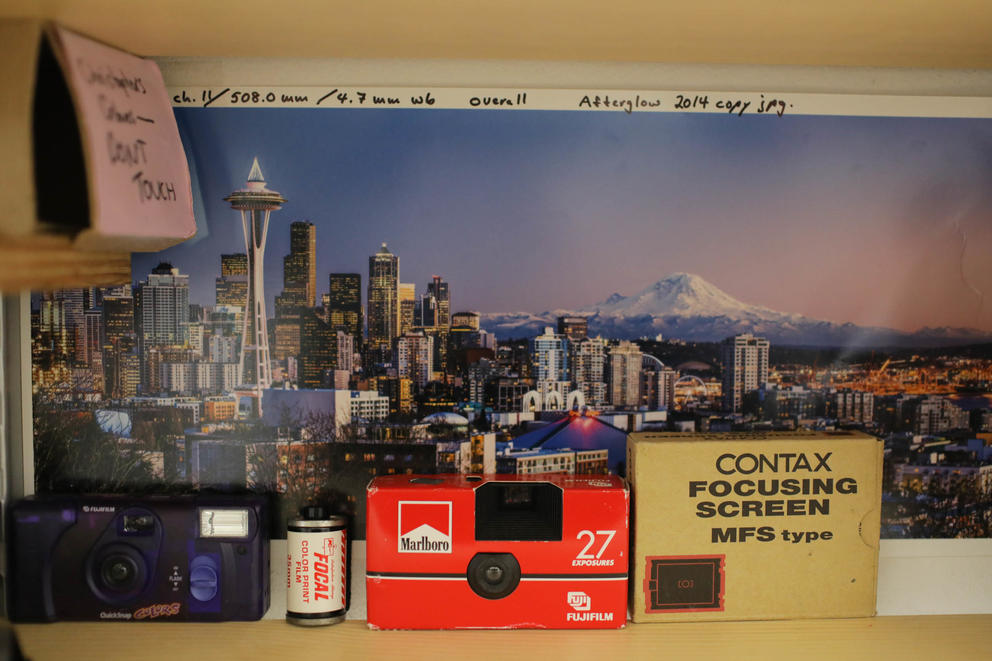

A slightly metallic vinegar aroma hints at the chemical magic of the film developing in progress nearby. Disemboweled disposable cameras fill an open cardboard box. A small bin contains the shells of cracked-open 35mm film cartridges, a mix of Kodak’s telltale turmeric yellow and Fujicolor’s Kermit green. Tresses of translucent brown film negatives hang from racks like strands of kelp. Along the walls, shelves heavy with white paper envelopes contain printed photos and developed negatives waiting to be picked up.

“In 2016-2017, we were probably doing 50 to 75 color rolls a day, maybe another 50 to 75 black-and-white a week,” says Fleenor, Panda Lab’s owner and manager. “I’d say now we’re easily doing around 100 color rolls a day and about 100-200 black-and-white rolls a week.”

A doubling in sales is noteworthy for any business. What makes the numbers remarkable in this case: A decade ago, media experts had declared film photography as good as dead.

But, as Fleenor and others proclaim under Instagram and TikTok posts featuring analog photography: #FilmIsNotDead. “Film is still very much alive,” Fleenor says. And perhaps surprisingly, the comeback is in large part driven by a generation of “digital natives” who developed a love for film photography and classic film cameras during the pandemic.

“It’s, like, cool [now] to go out with your friends for a night and have a 35mm point-and-shoot camera rather than just your iPhone,” says Rebecca Kaplan, the manager of Glazer’s Camera, a longtime local camera and film store and camera rental business anchored in South Lake Union. “People are really drawn to the analog aspect of it because our lives are so digital and so high-tech.”

Sales of film rolls and disposable cameras at Glazer’s have increased roughly 50% in recent years, Kaplan explains in her compact office on the store’s main floor. “It’s one of our fastest-growing departments in the business,” she says.

Photography-oriented nonprofits in the Northwest are feeling the surge too. Darkroom classes at Youth in Focus now have a waiting list — a new phenomenon — according to executive director Samantha Kelly. At Photographic Center Northwest, executive director Terry Novak says they’ve seen a “flood of new faces” for its introductory workshops in black-and-white photography and darkroom techniques.

“The demographic seems to be skewing younger and also more diverse,” Novak says about enrollment over the past few years. Local meet-up groups like Ferries on Film and Seattle Film Club are drawing increasingly larger crowds of budding film fans, sharing know-how and providing community in on and offline groups.

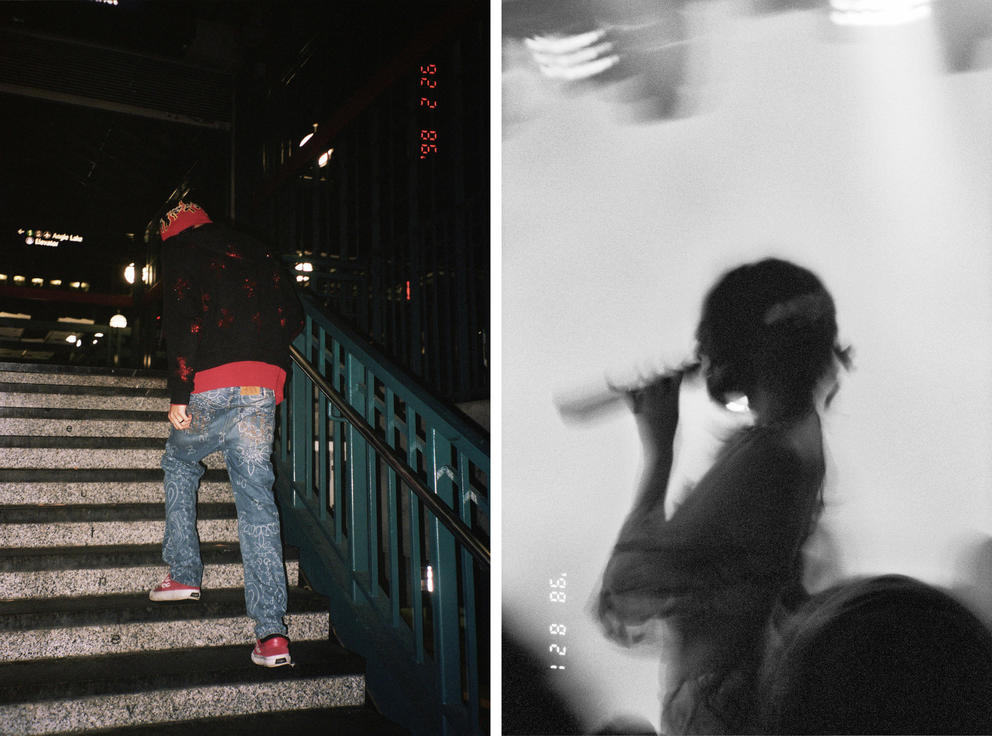

Katie, a local photographer, reloads a camera during a Seattle Film Club and Ferries on Film meet-up. Liv Lyons, a professional photographer in Seattle who started shooting film regularly during the pandemic, says the medium has been an escape for her. “It slows me down [and makes me] be intentional and focus on what I'm seeing one frame at a time rather than 30 frames per second. Without film, I'd be creatively and photographically burnt out.” (Shot on film, courtesy of Liv Lyons)

During the pandemic, Anna Starr started shooting with a Holga toy camera, a simple camera with a plastic lens that creates “dreamlike” photos, as Starr puts it. She helps host a Seattle-based photography group called Ferries on Film. The group meets monthly and rides the ferry together to take photos. (Shot on film, courtesy of Anna Starr)

Anna Starr loves shooting film because of its intentionality. “When I used to go out hiking, I might snap 50, 100, 200 photos on my phone and never really go back to appreciate them or even think about the fact that I just took a HUNDRED photos. … Between the cost and the process, I'm a lot more selective about what I shoot. It makes each shot a little more meaningful when you have to try a bit harder to create a good image.” (Shot on film, courtesy of Anna Starr)

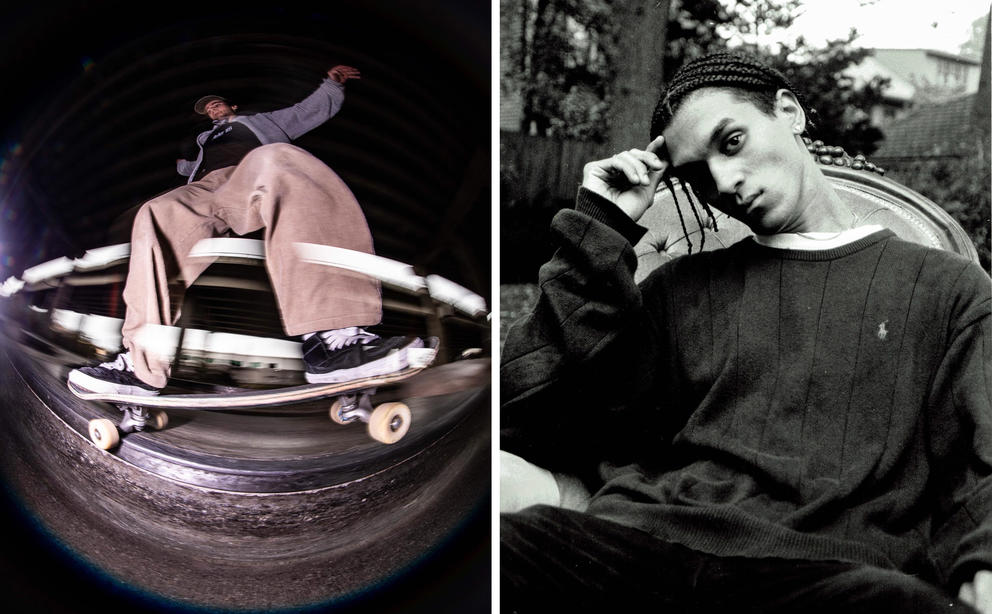

A participant named Letao scopes out the scene at a Seattle Film Club and Ferries on Film meet-up. “I’ve definitely noticed a resurgence in interest in film photography; it's almost inescapable but in a cool way,” says Seattle photographer Liv Lyons, who helps host and run the Seattle Film Club meet-up group and online community for film enthusiasts. “Whether I'm at a local coffee shop, walking around downtown, or covering a sporting event, I'll see at least one other person with a film camera. Every time, without hyperbole.” (Shot on film, courtesy of Liv Lyons)

Hannah McCloud has been shooting film for years and says filters on digital photos just can't create the same effect. “People definitely use filters on different apps to give their photos that 'film' look, but I think there’s something lacking there because many people are still choosing disposable film cameras and regular film cameras over those apps.” In addition, she says, “there’s maybe a novelty aspect of using film cameras, especially disposable film cameras, that can’t be achieved by using a filter app. (Shot on film, courtesy of Hannah McCloud)

Big photo brands are also benefiting from the renaissance. In early October, iconic film camera company Kodak announced it had hired more than 300 people in the past 18 months, and that it was looking to recruit more. “Consumer demand, particularly for 35 mm film, has exploded over the last few years. Our retailers are constantly telling us they can’t keep these films on the shelves — they want more,” said Nagraj Bokinkere, Kodak’s vice president of industrial films and chemicals, in a recent podcast interview. “We literally cannot keep up with demand.”

Leica followed suit a few days later by announcing it would bring back the M6, a 35mm film camera it introduced in 1984 but stopped producing 20 years ago as digital photography took over. Meanwhile, new and longtime film producers alike are racing to satiate the demand by releasing new films or reviving discontinued film lines.

It’s a complete reversal from the early 2000s, when major film companies stopped making many of their analog cameras and film, shuttering production plants and halting sales. Now that interest is booming as supply chain issues continue, there’s just not enough stock to go around. That has resulted in price increases and even retail rationing of certain film rolls (like the Portra400) made popular through Instagram and TikTok hashtags. Local photo stores say it’s hard to source enough vintage cameras — everything from point-and-shoot to more complex models — for resale. And good luck finding a cheap camera at a thrift store these days.

While such shortages can be frustrating for eager hobbyists, film’s comeback is widely embraced by professionals and newbies alike. “It’s really exciting,” Fleenor says. “It started growing before the pandemic, and then once the pandemic hit, it grew quite a bit… we’ve been pretty much screaming busy ever since.”

Ten years ago, Panda Lab employed seven people. That number has grown to 12 due in large part to the film renaissance, which, Fleenor says, is driven mainly by high school- and college-aged customers.

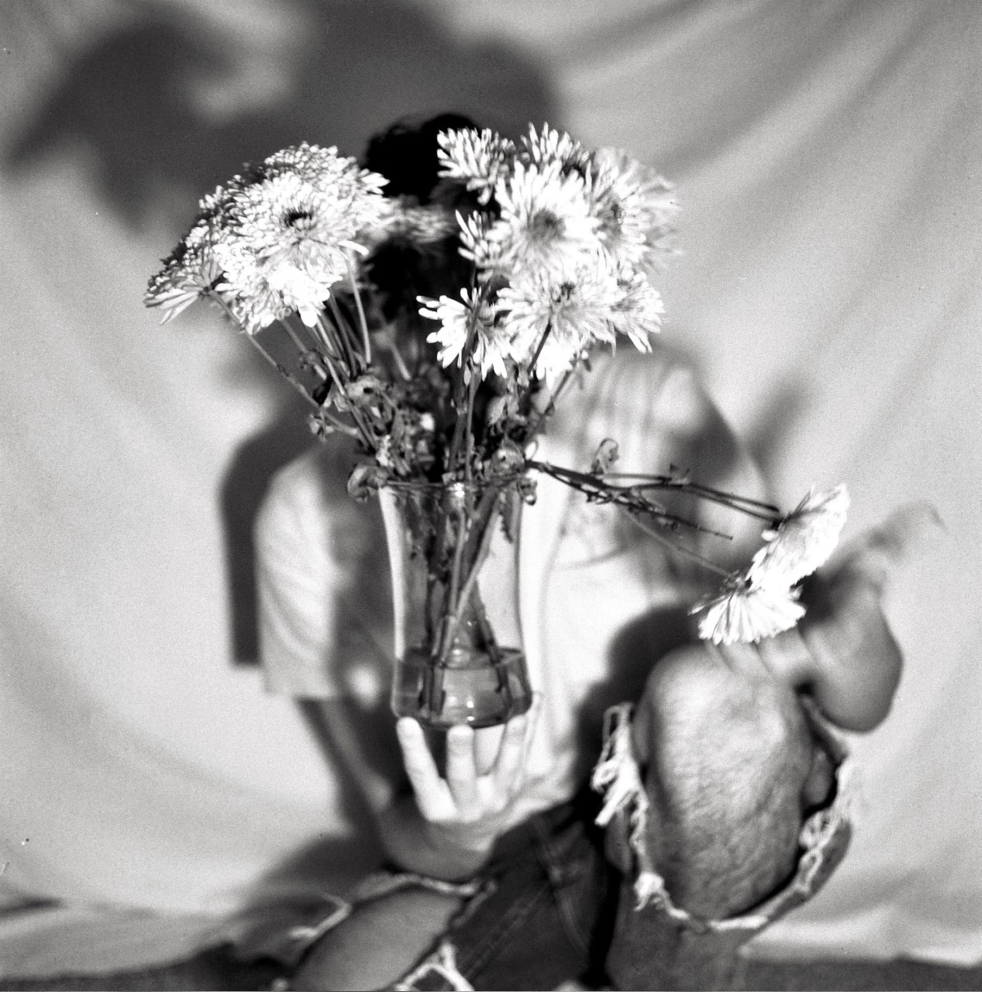

One of them is Chase Marshall. Stuck in the dorms at Bellevue College and “bored out of my mind” in the fall of 2020, Marshall decided to get an analog camera after stumbling on a YouTube video of a film photographer at work. Not long after, he went to Glazer’s, rented the exact same camera (a Mamiya RZ67), and fell in love. “It just felt magical,” Marshall says. He’s been doing fashion shoots with friends and acquaintances ever since, and now works part-time at Panda Lab. Though he’s dabbled in digital photography before, film, to him, is the real deal.

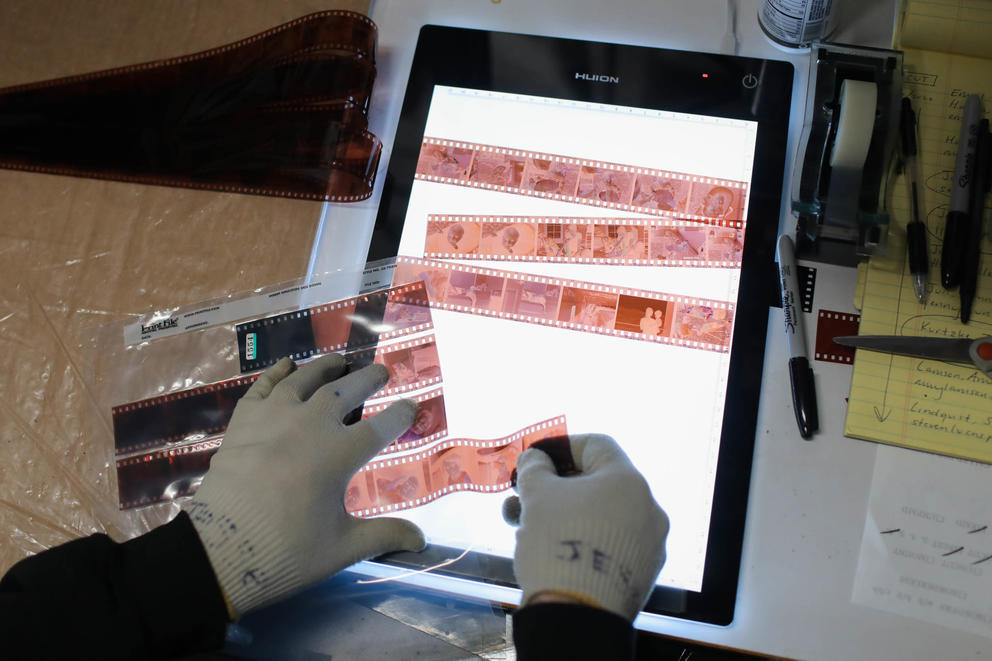

“It’s a certain aesthetic… that’s hard to replicate on digital,” Marshall says. Using gloved hands, he ensures there’s no dust sticking to a customer’s roll of negatives. “Digital sometimes, to me, feels a little bit too flat. But with film, there’s a lot more texture, rawness — it makes it feel like you’re there within that scene of that photograph.”

To many film photographers, the medium offers everything the smartphone cannot. With (commonly) 36 photos per roll, film represents limits in an age of abundance. Thanks to a standard waiting time of a week or more to get film developed, it also means patience in an era of instant gratification. And because of the medium’s natural grain — and the possibility of light leaks, double exposures, flares and other mishaps — it promises high relief and texture in a time of digital sleekness. Much like with the vinyl-record resurgence, film fans speak of “soul” and “warmth,” of irreplicable imperfections.

“iPhone photos typically feel very perfected, and they’re very high-quality images,” says Hannah McCloud from behind the counter of Omega Photo. The store shares a spot with a nail salon, tattoo shop and florist in a low-slung strip mall in downtown Bellevue. McCloud, a film photographer and Omega Photo employee, has witnessed the film photography boom firsthand. “The drive to do more film photography represents maybe fighting against digital technology and Instagram and perfectionism,” she says. “I’ve had people come into the store and they’re like: ‘Give me a camera that’s gonna make my photos look super-messed up and terrible.”

Still, the irony is those anti-Instagram imperfections have been trending on… Instagram and TikTok, where celebrities like Kendall Jenner, influencers and new converts to the medium share their analog film photos in the form of slideshows, digital photo collages or fast-moving succession reels — a digital-era version of the projector slideshows of yore.

“Kind of a cool hybrid,” Fleenor of Panda Lab says about the influx of old-school film photos on social media. “You get the benefits of digital and the soul of film.” Many customers who get film developed forgo the negatives and physical photos altogether, instead paying to get their digital photo files sent to them electronically. (Fleenor has one employee tasked with reminding people to pick up their physical prints or negatives.)

With this new generation of photographers going straight from celluloid to pixels, it’s hard to fathom the current trend being as wide-reaching and explosive as it has been without the help of social media. In a sense, the new medium is crucial to the survival of the old medium.

Social media hasn’t just made film cool, it’s also made it more accessible, says local photographer Emily Deering. She points to a host of YouTube, TikTok and Instagram videos that explain how to load a roll of film into a camera, or things like what exactly an exposure triangle is. It’s an inclusive online community, Deering says. “It’s encouraging people to just give it a try. They’re trying to make it easy, like: ‘Hey, grab a camera from Goodwill,’” she says. “‘Just give it a go.’”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.