I’ll be honest: Before seeing it in person, Golden Harvest: Flour Sacks from the Permanent Collection was perhaps the least enticing of several exhibits I intended to check out in Spokane and Pullman. It sounded a bit dry. I had concerns about burlap. But it turned out to be one of my favorites — and it seems I’m not alone: The show was just extended through Jan. 22, 2023.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

Pulled largely from the donated collection of W.A. Peters, who owned the Spokane Flour Mill until it shut down in the early 1970s, these flour sacks are fascinating. (Stay with me!) They date from the flour sack’s heyday — between the 1880s and the 1940s. Prior to that, flour was shipped in barrels; afterward, paper bags became all the rage. Spokane was one of the largest American producers of flour during this time, and the exhibit reveals that as early as 1860, exporting flour was a big part of the business (and still is).

What I love about these simple cotton sacks is how they’re decorated: with distinctive graphic designs, tailor-made for wholesale buyers. A sack stamped “Las Mariposas” and destined for San Salvador is adorned with detailed butterflies in red, yellow and green. On a “Pato” brand bag marked for Manila, a proud duck holds four shafts of wheat in its beak, as well as a waving ribbon reading “Purity” and “Uniformity.”

Many of the bags are branded for Hong Kong buyers, with artful designs including a dragon, an orange tree and water lilies. And on the domestic sacks: an elegant 1920s “flapper,” a skinny gamecock and a hand holding four aces.

As I sifted through flour-sack revelations — secret flour codes employed in international business telegrams during times of political unrest; Depression-era repurposing of flour sacks for household linens and clothing — one mystery was left unsolved: Who were the artists behind the flour-sack art? Their names have disappeared in a poof of white powder.

The Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture is also showing an exhibit of American Impressionism, a lovely retrospective of longtime Spokane artist Lila Shaw Gervin, and a lively and wonderful exhibit of Mexican masks and danza regalia. Curated by Gonzaga professor Pavel Shlossberg, Dancing with Life (through Apr. 16, 2023) emphasizes the vital role of mask-making in contemporary Michoacán, Mexico. With depictions of devils, holy figures, Picasso, Donald Trump, icons and false idols, these masks reveal an Indigenous tradition very much alive today.

After the visit, my husband and I headed south along the spectacularly gorgeous Palouse Scenic Byway — landscape painting on a grand agricultural scale. The rolling fields of yellow and green crops (wheat, lentils, barley, garbanzos) appeared soft as velvet as we motored toward the shining and square Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art on the campus of Washington State University.

Designed by noted Seattle architect Jim Olson (of Olson Kundig), the mirrored “Crimson Cube” is impossible to miss. When we pulled up, Executive Director and Curator Ryan Hardesty kindly stuck around late on a Friday to show me the exhibits.

As we stepped into the first of several galleries, 12 oversized, traffic-cone-orange resonator horns mounted on the ceiling came alive with mournful, motion-activated chords. The museum commissioned Northwest “sound sculptor” Trimpin to create Ambiente432 (the installation is tuned to 432Hz) for the building’s opening in 2018.

“This used to be a public safety building,” Hardesty told me, noting that the concrete floor in this room still bears evidence of the fire trucks and police cruisers that once occupied the garage. Now it provides a different kind of public service, as a space for “meditations, cello concerts, celebrations, improvisational dance and other art-and-healing events,” he said. I stood for a moment and let Trimpin’s chords — set at a reportedly healing frequency — sink in.

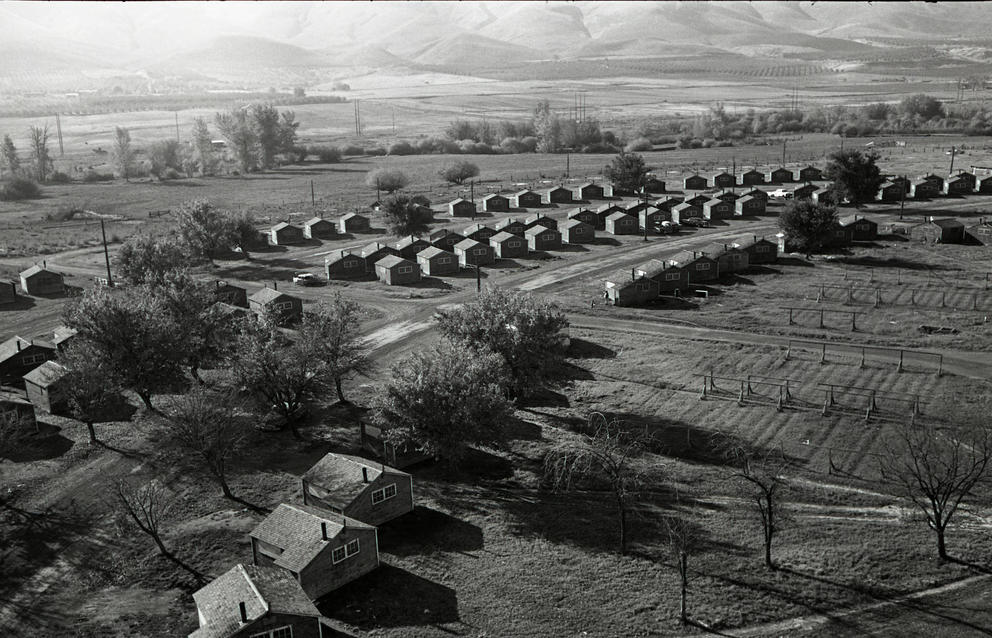

Also on view in the chapel-like space is an exhibit that, similar to Spokane’s flour sacks, points to the crucial agricultural history of Eastern Washington. Our Stories, Our Lives: Irwin Nash Photographs of Yakima Valley Migrant Labor (through March 11) features 40 black-and-white photographs — from a collection of some 9,400 — taken by the Seattle photographer Irwin Nash from 1967-1976.

Nash originally went to Yakima for a one-time freelance assignment, but was so compelled by the farm workers he returned every summer for 10 years, befriending the families and working to “call attention to the plight of a segment of the population that has never received the recognition and compensation merited by their contribution to our society,” he wrote.

The images are both striking and everyday — a woman harvesting asparagus, a band performing, kids playing. Last year WSU digitized the entire collection and made it browsable online, with the aim of helping to identify and contextualize the images by way of extended family.

Across the hall is Juventino Aranda’s Esperé Mucho Tiempo Pa Ver (I Have Waited a Long Time to See), a survey of work by the Walla Walla-born Mexican American artist. (Many of these pieces were also on view at Greg Kucera Gallery this past summer.) His paintings and sculptures — featuring a police line, a bronze Beanie Baby, house-painted Pendleton blankets — reveal his critical eye toward American pop culture and hypocrisy.

Lastly we walked through a big, vibrant exhibit of paintings and encaustics by an artist who was born in South Korea, raised in Japan, taught at Whitman College and is based in Walla Walla. Keiko Hara: Four Decades of Paintings and Prints (through Mar. 4) surveys work from the abstract artist’s ongoing series of “Topophilia” (“a strong love of place”). Hara’s bold and speckled planes of green, gold and blue stayed in my head as we drove through the wheat fields toward home. I’ll be back for more inland art!

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.