This story is part of Crosscut’s 2022 Fall Arts Preview

As it prepares to launch its 50th anniversary season (Sept. 23 at McCaw Hall), PNB is basking in the aftermath of successful summer tours to New York and Los Angeles. With almost 40 dancers on full-time contract, its own critically acclaimed orchestra and a thriving ballet school that serves hundreds of students in both Seattle and Bellevue, PNB has earned an international reputation for excellence.

But the company isn’t resting on those laurels. PNB is now pushing the edges of classical ballet: seeking out new repertory, new choreographers and new BIPOC dancers like Wimpye. The goal is to reflect America’s diversity, onstage and off.

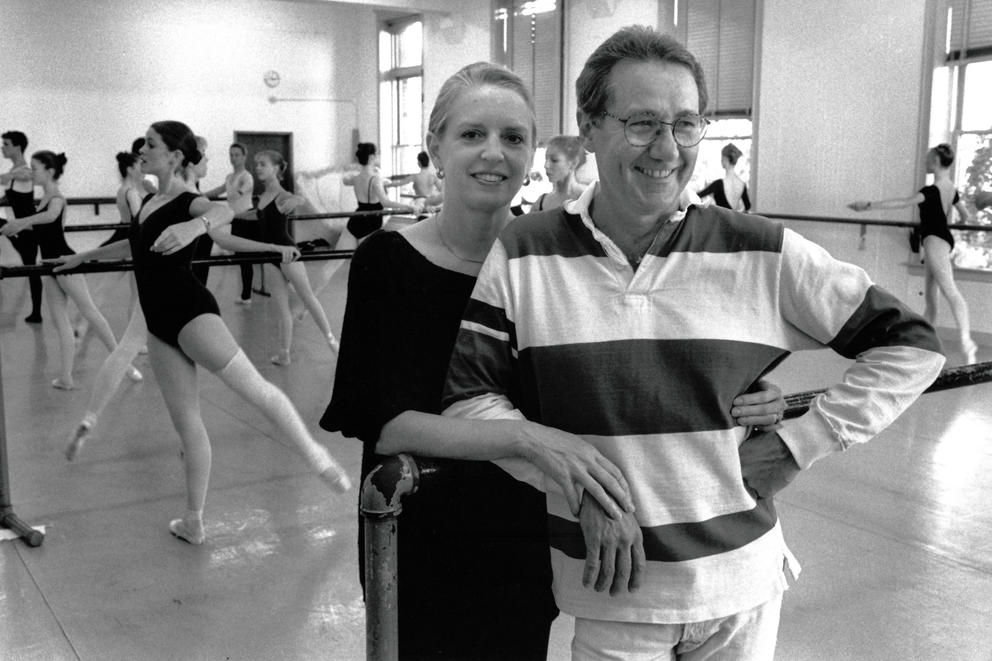

Founding artistic directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell likely never imagined PNB’s current iteration when they took over the fledgling dance troupe in 1977. At that point they could only dream that their struggling company would make it to age 50, let alone become a national powerhouse.

The Pacific Northwest Dance Association, as it had been known since its founding in 1972, started as an arm of Seattle Opera. It had a handful of dancers, a haphazard class schedule, and very little money to improve either situation.

“The place was chaos,” Russell recalls. “But we looked around, evaluated the situation … rolled up our sleeves and got to work. It was like climbing Mount Everest!”

Stowell set out to recruit dancers while Russell was charged with starting a school that ultimately could produce new generations of PNB-grown artists like Wimpye. The duo managed to negotiate the company’s independence from Seattle Opera in 1977, and the following year rechristened it Pacific Northwest Ballet. Just a decade later, with two dozen dancers under contract, PNB was touring regularly up and down the West Coast, had performed in Asia, and made its New York debut.

Despite attracting audiences, money remained scarce. Without the funds to license or commission work, PNB relied heavily on a repertoire created by Stowell, as well as a healthy selection of ballets provided free of charge by New York City Ballet founder George Balanchine. Stowell and Russell both had danced for Balanchine at NYCB, where Russell had served several years as ballet mistress. The Balanchine and Stowell ballets remained PNB’s foundation through Stowell and Russell’s 28-year tenure.

“With Kent and Francia we used to do a lot of large scale, classical works,” says Kiyon Ross, who came to PNB as a student in 2000, and then, under the name Kiyon Gaines, danced with the company from 2002 until his retirement in 2015. Ross now serves as PNB’s director of company operations.

“I think Kent and Francia were very particular about having strong classical technique,” he continues. “The picture is bigger now.” Ross points to an expanding repertoire of new works that require a cadre of dancers proficient in techniques beyond ballet: everything from jazz and tap to contemporary styles performed in socks instead of the traditional pointe shoes or ballet slippers. Although Stowell and Russell did program some contemporary ballets, Ross says the move to new work accelerated after current artistic director Peter Boal arrived in 2005.

Boal, who’d spent his onstage career with New York City Ballet, was steeped in the same Balanchine choreography that had shaped Russell and Stowell’s artistic vision. But from Boal’s first year in Seattle, he was intent on charting a new course.

“I put up some wacky programs in my first couple of months,” Boal laughs. Looking back, you’ll find Balanchine and choreographer Jerome Robbins on the same bill as an aerial ballet called The Kiss. Despite ticket holders’ sometimes vehement and vocal disagreement with his artistic choices, Boal persisted with his goal of “refreshing” PNB’s repertoire. Over his 17-year tenure he’s added ballets by such acclaimed contemporary choreographers as Twyla Tharp, Crystal Pite and Alexei Ratmansky. And he’s sought out new works by up-and-coming artists like Alejandro Cerrudo, Jessica Lang and Penny Saunders.

To make room for this new repertoire, Boal has winnowed out some of the works that had been PNB’s bread and butter. Perhaps most controversial, in 2015 he replaced the company’s long-running Nutcracker production, featuring Stowell’s 1983 choreography and original sets and costumes by Maurice Sendak, with Balanchine’s 1954 version. Boal commissioned another children’s author/illustrator, Ian Falconer, of the Olivia book series, to create new designs.

For many longtime PNB fans, Boal’s decision to jettison the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker seemed like a slap in the faces of Stowell and Russell. The couple, and many of their supporters, consider Stowell’s version of the holiday classic a seminal milestone for the ballet company, distinguishing it from troupes that relied on the older Balanchine work. They credit the Stowell/Sendak ballet for everything from audience development to fundraising to enrollment growth at the PNB school.

Pacific Northwest Ballet dancer Christian Poppe (center) as the Cricket (with PNB School students Celena Fornell and Emerson Boll at left and right), a new role in the new staging of "Nutcracker." PNB worked with the George Balanchine Trust to replace the original costuming of the central character in the “Chinese divertissement” segment, which was based on racial stereotypes, with a new Green Tea Cricket character for the 2021 production. (Angela Sterling)

People were unhappy with Boal’s decision to replace the ballet seven years ago, and tensions escalated even further earlier this year when PNB’s technical director, Norbert Herriges, authorized the destruction of most of the Sendak sets and backdrops. Herriges’ decision came as a surprise to the ballet company’s administrative staff, who declined to discuss the issue publicly.

Although PNB had no plans to revive the Stowell/Sendak Nutcracker, ballet companies in other parts of the country had expressed interest in renting the sets and costumes (which remain intact). That potential revenue stream is now closed. And destroying the Sendak sets provoked larger questions about the value of PNB’s history.

In March, Stowell and Russell wrote to PNB’s board of directors, asking them to open a discussion about the stewardship of their artistic legacy. They wanted to know if “plans are underway to recognize and celebrate the many constituencies that have brought PNB” to its 50th anniversary, making the case, in particular, for full-length ballets.

In the letter, the couple also took an indirect swipe at Boal’s decision to beef up the company’s contemporary offerings. They wrote that programming a regional company like PNB requires balancing one’s personal preferences with programs that will attract as wide an audience as possible.

For his part, in crafting programs for the anniversary season, Boal says he absolutely considered “the choreographic pillars upon which this company was founded.” He wanted to honor Stowell and Balanchine, while at the same time making clear that he sees contemporary work to be fundamental to PNB’s future.

The season opens with a triple bill that includes Stowell’s Carmina Burana, Balanchine’s Allegro Brillante and a world premiere by Ratmansky. Next spring fans of traditional story ballets will welcome Giselle and Balanchine’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, plus a PNB School performance of Snow White for young audiences. But the six regular-season programs boast six world premieres including Ratmansky’s ballet — a clear indication of Boal’s commitment to contemporary dance.

“You can do all the modern stuff,” Stowell said in an interview earlier this summer. “But I think audiences are going to come to Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake.”

He may be right.

Drawing audiences back to McCaw Hall is of utmost concern as PNB struggles to recover from the pandemic’s economic fallout. In the aftermath of mandated closures in March 2020, the company canceled the remainder of that year’s programs, as well as all in-person performances for the following artistic season. PNB laid off or furloughed some of its staff and slashed its $24 million annual budget in half.

“I worried that ballet was going to die during the pandemic,” Boal says.

PNB was able to keep its head above water thanks to emergency grants and loans, specifically $8 million from the federal Shuttered Venues Operating Grant fund. Although the company did welcome back in-person audiences in September 2021, they capped ticket sales at 60% of McCaw Hall’s 3,000-seat capacity, and required both masks and proof of vaccination or negative COVID tests to enter the theater.

And while PNB drew new audiences to its digital offerings, Boal acknowledges those lower-priced tickets can’t make up for lost revenues. “There’s a lot of rebuilding that’s needed,” he says.

Getting butts into seats is crucial, but perhaps of equal importance to Boal and his PNB colleagues is who makes up the audience — and the company itself — going forward.

The 2020 murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor reinvigorated the national movement for racial justice, and intensified work that already had been underway at PNB. In its early years, the vast majority of PNB dancers were white. For most of his performing career Kiyon Ross was the company’s only Black dancer, following in the footsteps of the late, beloved PNB dancer Kabby Mitchell.

Perhaps because of PNB’s Pacific Rim location, the company roster has featured a number of Asian and Asian American dancers, including retired principal dancer Le Yin, who joined PNB in 2002. But Ross credits Boal and executive director Ellen Walker for seriously committing to diversify the company starting almost a decade ago. Walker says 50% of company members this season identify as people of color, compared to 27% 10 years ago.

Amy Brandt, editor-in-chief of Pointe, a national ballet publication, says PNB’s work is in line with what’s happening at most American ballet companies, which are working to diversify their rosters and increase training opportunities for people of color.

“Under Peter Boal, PNB has been several steps ahead of most major U.S. companies when it comes to these issues,” Brandt said in an email. But she cautions that ballet companies still have work to do in other areas of access to the art form at its highest level. “I would say movement has been slower when it comes to body type, and a lot slower when it comes to gender identity.”

PNB is actively “de-gendering”: It now classifies roles as either “pointe” or “flat” shoe, rather than male or female, and the company’s school has opened pointe and partnering training to committed students of all genders. Last season, PNB welcomed apprentices Ashton Edwards and Zsilas Michael Hughes, both of whom identify as nonbinary. This year, they join the corps de ballet. Already, Edwards has performed roles in Swan Lake and Nutcracker that previously had been reserved for cis-gender females.

Ross believes opening ballet to a wider pool of performers is a healthy step both for PNB and for ballet in general.

“I’m encouraged by how other people will see what our stage looks like,” Ross says. “Hopefully more dancers of color will be encouraged to try our art form, because they see themselves represented out front, dancing leading roles.”

Three of the five PNB School students joining the company this season are Black dancers. Incoming apprentice Wimpye is thrilled to be part of the changing face of ballet.

“I’m glad to be part of a company that is really pushing the narrative,” she says. “To see more people that look like me would be even better.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.