“Dance is about lifelong well-being,” she says. And the almost 80-year-old Seattleite can point to herself as living proof.

Daigre founded Seattle’s Ewajo Dance Studio in 1975 and taught there for more than 30 years. In 2015 she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a blood cancer. She had thought she was simply anemic, so the news stunned her. But her doctor told her she would probably die of old age before myeloma, and Daigre wasn’t ready to start drug treatments or other medical interventions.

For decades, she has set aside time every day to dance, practice Pilates or just take a walk. She credits her daily movement, combined with breathing, strengthening and balance exercises (plus a little luck) with helping her to manage her cancer without medication.

Recently, she has developed and refined a movement regime aimed specifically at seniors of color — a population Daigre believes is too often ignored by mainstream health and fitness trainers. She calls her program Dance for Health, and every step she teaches she has tried out on her own body. (Ewajo Dance Studio has closed, but seniors interested in her new class can contact ewajocentre@gmail.com.)

Daigre started dancing 70 years ago, in her hometown of Gary, Indiana. “In the fifth grade,” she recalls, “I saw an African American ballerina and I wanted to do that!”

That ballerina was Katherine Dunham, founder of one of the first Black ballet companies in the United States, who later studied Caribbean and African dance idioms and forged her own movement technique.

From the beginning, Daigre showed an aptitude for everything her community center dance teachers threw her way. They encouraged the skinny girl with bowed legs and a speech impediment to continue taking classes.

Dance gave her an outlet for self-expression. But neither she nor her parents viewed it as a viable career path, so Daigre trained to work in health care. Despite her full-time career, she didn’t stop dancing, and when she and her young son, Chris, arrived in Seattle in the early 1970s, Daigre founded the community studio called Ewajo Dance Center. The name comes from the Yoruba word for “common dance” or “dance of the people.”

At Ewajo she taught the dance styles she loved to everyone from high school students to retirees to aspiring professional dancers. Before long, Daigre was leading classes across the city. She estimates that, over the decades, she has reached hundreds, perhaps thousands, of students.

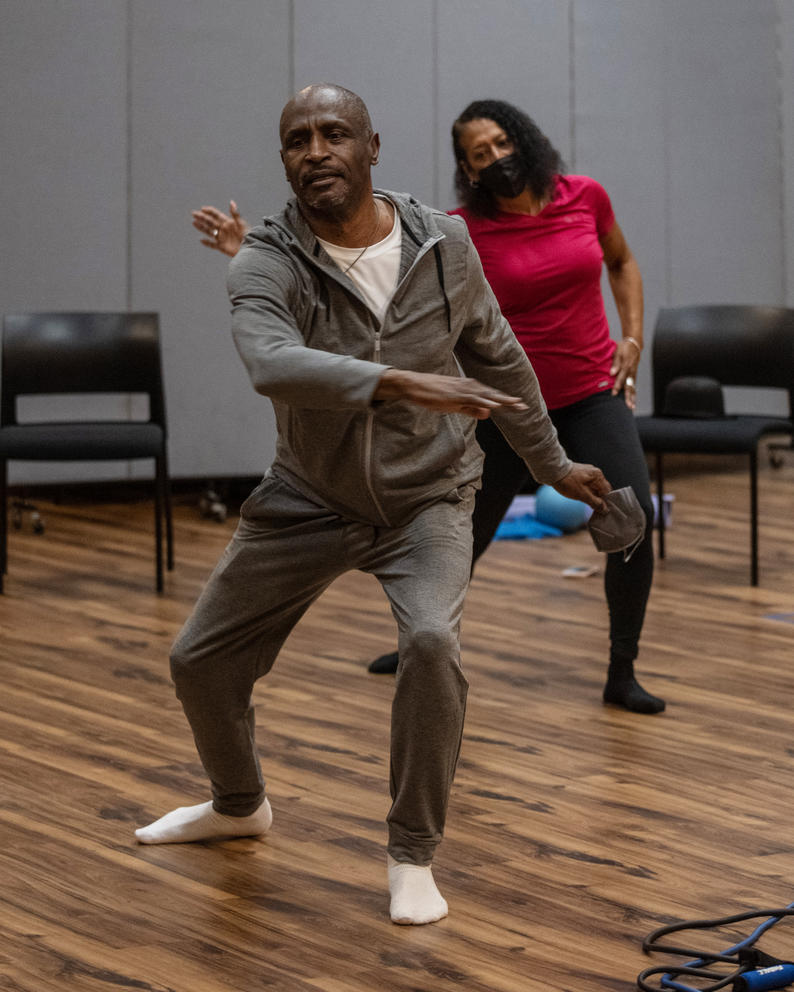

Students (including Diane Powers, in pink) move to the music during a Dance for Health class with Edna Daigre at MLK FAME Community Center in Seattle, WA on March 5, 2022. (Chona Kasinger for Crosscut)

Diane Powers was in high school when she met Daigre in 1974 at Seattle’s now-defunct Black Arts West.

“Edna was not just a teacher,” Powers says. “She made us feel seen and heard. She taught us that everything you put into your body can either heal you or cause disease.”

More than 50 years later, after a dozen years dancing on Broadway, Powers is now a Dance for Health regular. “What I get from Edna helps me with everything — flexibility, strength. I couldn’t get that from a gym,” she says.

Daigre starts each class slowly, showing her students how to breathe deeply into their diaphragms, releasing each breath while isolating movements in individual body parts: rolling their shoulders, rotating the neck, lifting up to their toes to balance on one foot. By the end of the 90-minute session, students are grooving to music that runs the gamut from vintage Motown to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.

Everyone is having fun, and that’s clearly what Daigre is after.

But Daigre hopes to achieve more lasting results, too. She wants to help her older students prevent potentially debilitating falls, give them the endurance to bring a bag of groceries from the car to the kitchen. And if you want to shake your hips to Chaka Khan while you’re doing errands, that’s icing on the cake.

You don’t need dance experience to enroll in Daigre’s class, but some of her students, like 71-year-old Marvin Tunney, boast prestigious resumes.

Tunney’s professional career included stints with the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, Broadway choreographer Bob Fosse and appearances in such films as Stayin’ Alive and The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. He also spent years on the California Institute of the Arts faculty. Tunney now is in the early stages of dementia, but his body still remembers what to do when the music begins.

“I’m not trying to kick higher than anyone else, or jump higher,” Tunney says. “But as long as I have the mentality to move gracefully, then I feel like I am going to grow.”

Reflected in mirrors, Chris Daigre, in red, leads what he calls a "joyful dance experience" movement class at a private residence in Seattle, Washington, March 7, 2022. Chris, who was diagnosed with Parkinson's in 2019, assists his mother Edna Daigre with her Dance for Health classes and teaches his own classes across the city. (Lindsey Wasson for Crosscut)

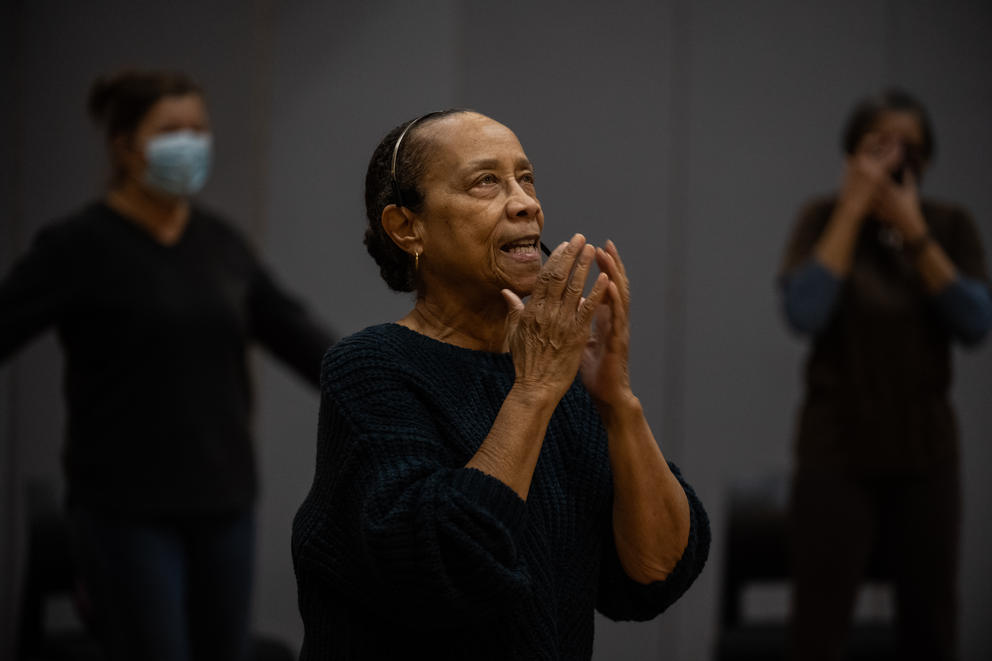

Edna Daigre’s son, Chris, 58, started assisting his mother at Ewajo when he was just a teenager and followed her into dance education. Before the pandemic he led a citywide series of popular classes under the auspices of his own business, danceDaigre. He gained a more personal respect for the relationship between movement and health after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2019.

“I didn’t know much about it,” he remembers, “but I realized that moving is the best thing to slow it down, to keep it at bay.”

Building on his mother’s experience melding dance and therapeutic movement, Daigre developed a program aimed specifically at people with Parkinson’s. (The Mark Morris Dance Company has also developed its own Dance for Parkinson’s program, taught in the Seattle area through the Seattle Theatre Group. There is no official relationship between it and Daigre’s work.)

Chris Daigre has been open about his health status, but his mother has been reluctant to reveal her cancer diagnosis to her students — and to the wider dance community — until this year.

“I thought it would keep me from teaching,” she says. “People would have the feeling that the class is not good because I have cancer now.”

Longtime student Diane Powers feels the exact opposite.

“Here’s this woman, carrying this disease and still teaching,” Powers says. “To me, she’s saying, ‘I’m going to live, not start dying.’ ”

For Edna Daigre, living means dancing, and vice versa. She’ll turn 80 this summer, but she has no plans to slow down. In fact, as pandemic restrictions ease, she’s excited to welcome students back to in-person classes at the MLK Center and Seattle Central College. And like the most ardent evangelist, she’ll be at the front of the room, Exhibit No. 1 for the health benefits of dance.

“I have to pass it on, I have to share this,” she says. “It’s just miraculous to be doing this at my age!”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.