“He cared about me as me,” says noted Seattle artist Barbara Earl Thomas, who first met Spafford when she took one of his entry level art classes in 1969.

She recalls one early encounter with the artist, who later became both her academic adviser and one of her most cherished mentors.

“I was very painstakingly drawing something. Painstaking, painstaking,” Thomas says. “And he took my tablet, threw it on the floor and jumped on it. He told me, ‘Stop drawing like you have table manners!’ ”

Thomas took Spafford’s criticisms to heart, and believes they helped her forge her path to becoming the artist she wanted to be. More than 50 years later, her paintings and elaborate papercuts have been exhibited in museums and galleries around the world, including currently at the Henry Art Gallery.

“He was lovable, for sure,” says another of Spafford’s appreciative former students, esteemed Seattle artist Mary Ann Peters. “But he was also someone who just didn’t mince words. In my graduate review he wrote, ‘I hope Mary Ann makes dozens and dozens of paintings so she can come up with a couple of good ones.”

Those words could describe Spafford’s approach to his own artmaking.

His son, photographer Spike Mafford, remembers his father coming home from working at UW, eating an early dinner, then retreating to his studio to paint for several hours every evening. He’d devote months to a single artwork, giving each one what Mafford describes as Herculean effort — fitting for a man whose paintings most often depicted figures from Greek mythology, often rendered in stark black and white, sometimes with slashes of red.

Mafford says he’d see what appeared to be a finished canvas in his father’s studio; the next time he visited, that canvas would be covered in a wash of white paint, which Spafford would subsequently cloak in black. Spafford built up layers of paint, then would carve through them, searching to re-create the image and emotion he held in his mind’s eye.

“He was always trying to make something better,” Mafford recalls, “until the painting he was working on was least unlike the way he wanted it to be. Those were his words.”

A painting might seem complete, but to the artist, it was unfinished. Spafford told Crosscut in 2018 that he was never satisfied with his paintings.

“If I live long enough, I’ll be able to do one I like,” he said.

And he doggedly pursued his quest.

In the late 1960s, not long after Spafford arrived in Seattle, he and his wife, artist Elizabeth Sandvig, joined the effort to expand funding for public art. In 1973, both Seattle and King County passed Percent for Art ordinances, which required 1% of any public project’s capital budget be set aside for art for that building. Shortly afterward, Washington state passed a similar law.

Spafford’s first commissioned public artwork, “Tumbling Figure: Five Stages,” a series depicting the fall of Icarus, was created in 1979 for an outdoor elevator shaft at the old Kingdome. When the stadium was demolished, the artwork was moved to a King County parking garage. “Tumbling Figure” sometimes provoked head scratching from casual viewers, but nothing like the controversy sparked by a work he created a few years later.

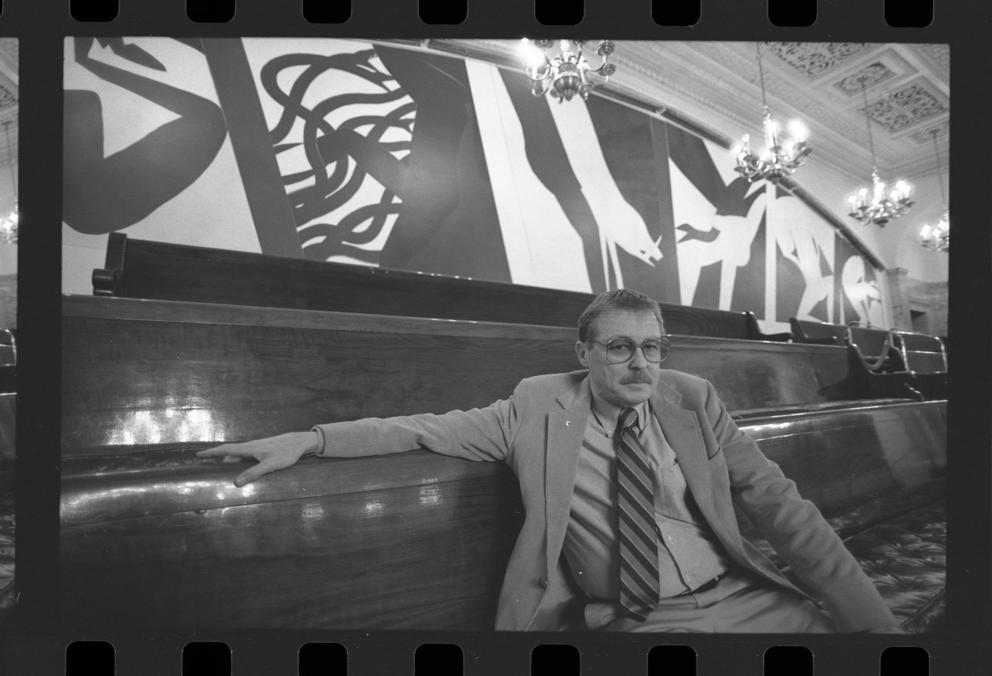

In 1980, Spafford received a commission to create a series of large murals for the state Legislature’s chambers. He based his site-specific paintings on the Twelve Labors of Hercules. Shortly after the murals were installed, some lawmakers publicly decried Spafford’s bold images as offensive, even obscene.

The murals were covered with drapery while a legal battle ensued over whether they should be removed from the statehouse and relocated, something to which Spafford vehemently objected. Lawmakers lodged similar objections to work by another longtime Seattle artist, Alden Mason, who joined Spafford’s fight to keep their artworks in place.

“When we defended Mike’s and Alden’s fight to keep the murals in the state Capitol building, I saw Mike at his finest,” wrote gallery founder and former Spafford student Greg Kucera in an email from his home in France. “He was resolute in his belief in the quality of his work, but he was understanding of how others could view it differently.”

Nonetheless, says Kucera, losing the fight to keep his murals in the place he specifically created them for was devastating to Spafford. Many people close to the artist believe that legal battle wasn’t just personally damaging; it also stymied his career.

Spafford’s daughter-in-law, Lisa Dutton, believes that, after the mural controversy, the painter retreated not only from public art, but also from putting himself out publicly. His paintings didn’t gain a wide following outside the Pacific Northwest, something Dutton and her husband, Mafford, strongly feel the work deserves.

“He didn’t want to talk about himself, he didn’t seek celebrity,” Dutton says. “His pride, and humility, kept him from being comfortable with public scrutiny.”

But Spafford continued painting and printmaking, even collaborating with his photographer son on several shows, starting with a series depicting the Labors of Hercules, which they exhibited in the early 2000s at the now-closed Francine Seders Gallery.

Last summer, father and son teamed up again for a show at Perry and Carlson gallery in Mount Vernon. The exhibit featured landscape photographs Mafford took on a family trip to Greece, onto which Spafford then painted his signature silhouettes. Gallery owner Christian Carlson says this kind of long-term family collaboration is a rare thing, something he was proud to showcase. A posthumous exhibition, Michael Spafford: Of Gods and Heroes, is currently on display at Portland’s Russo Lee Gallery.

“Michael was one of those people who thought it was truly about the work, it wasn’t about him,” says Barbara Earl Thomas. “In a way he was the perfect example of an artist going out and tackling ideas and creating work that demanded to be brought into the light, without any promise of what would come of it other than the fact that you made it.”

And while his art-world peers acknowledged his accomplishments, the fact that Spafford wasn’t more widely known bothered his son and daughter-in-law. In the spring of 2018, the duo spearheaded an unusual citywide retrospective of Spafford’s art, a three-gallery exhibition they titled Epic Works.

The Seattle galleries (Greg Kucera, Woodside/Braseth and Davidson) simultaneously presented a wide array of Spafford’s work, everything from prints and drawings to large paintings. Spafford attended the openings, spoke to crowds and collaborated on a book that accompanied the exhibitions.

“I think what Epic Works did was kind of heal him from the residue of the [state Capitol building] controversy,” says Dutton. “The galleries stepping up and eager to jump on board in this unusual way was just healing.”

In the last year of his life, Spafford’s health declined. After months in a skilled nursing facility, his family brought him back to the Montlake house he shared with his wife, son and daughter-in-law and two grandchildren. They cleared the living room so Spafford could continue to work, up until the end of his life.

According to Mafford, Michael Spafford wasn’t concerned about his legacy; he survives in the people whose lives he touched.

Former student Thomas says Spafford didn’t simply teach her about how to make art. He showed her what it was to live life with self-confidence and courage.

“Michael survived when his beliefs were not popular,” Thomas says. “I watched life take so much out of him, but saw him get up and go back to work, and not back down from the mark.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.