The first stop on the new extension is the U District station, designed by local LMN Architects and featuring big, zigzagging overhead tubes in blue and orange. In addition to bringing visual splash, LMN designed the lightning bolts of color help riders distinguish northbound and southbound trains. While waiting on the platform, 85 feet beneath street level, you’ll also notice a curious sight: what appear to be apartment windows, some with air conditioning units, and people moving behind them.

ArtSEA: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter.

This misplaced urban streetscape was created (using metal mesh sculpture and video installations) by Seattle-based Lead Pencil Studio, aka Annie Han and Daniel Mihalyo. Called “Fragment Brooklyn,” the 300-foot-long piece is a nod to University District history. In 1890, developer James Moore dubbed the area Brooklyn, in homage to New York City. “Beautiful residences were being built by some of the best people in the city,” Moore claimed, sounding like a certain ex-president.

Moore’s plan for a bustling “Brooklyn” was foiled by an 1895 infrastructure project, when David Denny put tracks for the new electric trolley line down University Way instead of Brooklyn Avenue. Some 125 years later, this new rail station opens right onto Brooklyn Ave. (For more 19th century hopes for the city, read Crosscut contributor Taha Ebrahimi’s recent story about a new exhibit of early promotional maps made to lure settlers to the Northwest.)

But back to the new light rail art. At the Roosevelt station, Italy-born, New York-based Luca Buvoli contributed “Mo-Mo-Motion,” a zooming series of abstracted bike-racing and running imagery. And at the Northgate station, longtime Seattle artist Mary Ann Peters created “Darner’s Prism,” a glass-paned paean to the official Washington state insect, the green darner dragonfly. Layering a visual representation of freeway sound waves with the leafy greens of nearby Thornton Creek, Peters hand-painted clerestory windows that reflect the urban nature of the surroundings.

Keep an eye out for more art when you pull up to these stations — and future stops in the ever-expanding light rail system. I wonder what the installations will look like 20 years from now, along the planned east corridor connecting Bellevue to Issaquah. Expected opening date: 2044.

Charles and Emma Frye also had an expansive civic vision for Seattle — that the city would always have a free art museum. The couple opened the Frye Art Museum in 1952, establishing from the get-go that access to the collection would never require an entry fee. That collection expands each year, and this month the Frye debuted the latest entries, Recent Acquisitions in Contemporary Art (through Jan. 23, 2022).

Among the seven thoroughly distinct works is a gorgeous piece by Anthony White, the Cornish College grad who two weeks ago won Seattle Art Museum’s prestigious Betty Bowen Award. (This year’s special recognition awards went to Seattle artists Humaira Abid and Tariqa Waters.) The award earns White a solo show at SAM in 2022, but the piece at the Frye is a prime example of his skill and artistry.

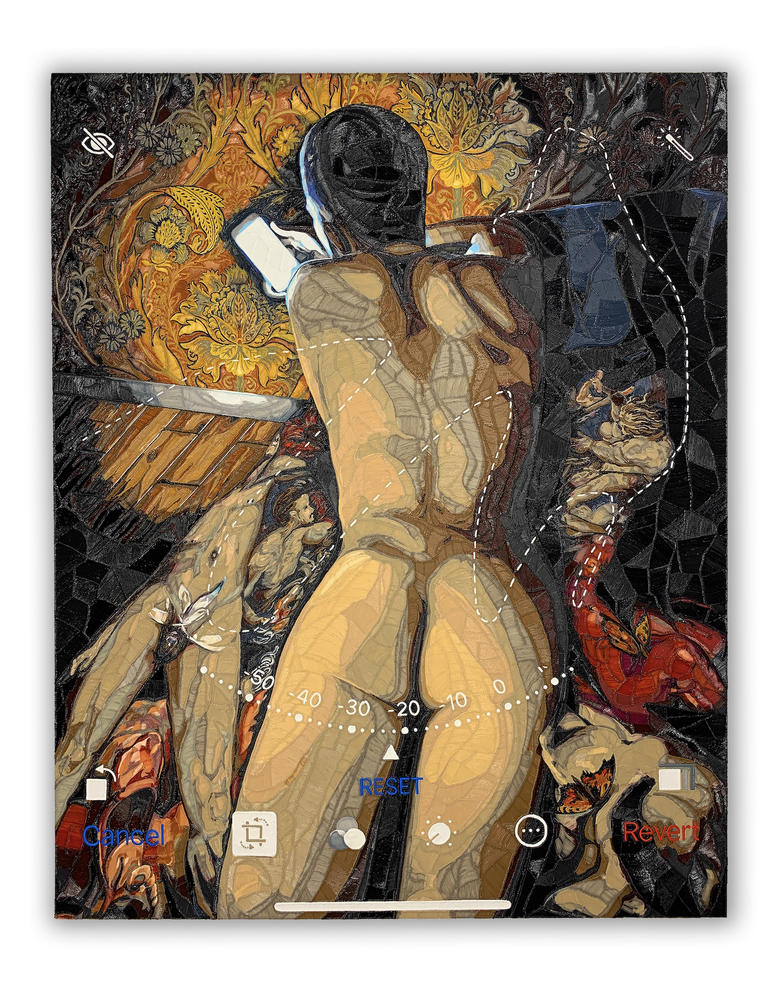

Using thin strands of extruded PLA plastic, White creates highly contemporary portraits and landscapes that reflect the current pop culture moment. “To a Flame,” at the Frye, is a kind of neo-nude, in which the body is shown as if seen through a photo-editing lens. In turn, the subject, lying on a bed on his stomach, is transfixed by the glow of his own phone. From a distance, the vision is lush and decadent. Up close, you can see the countless tiny threads that went into its creation.

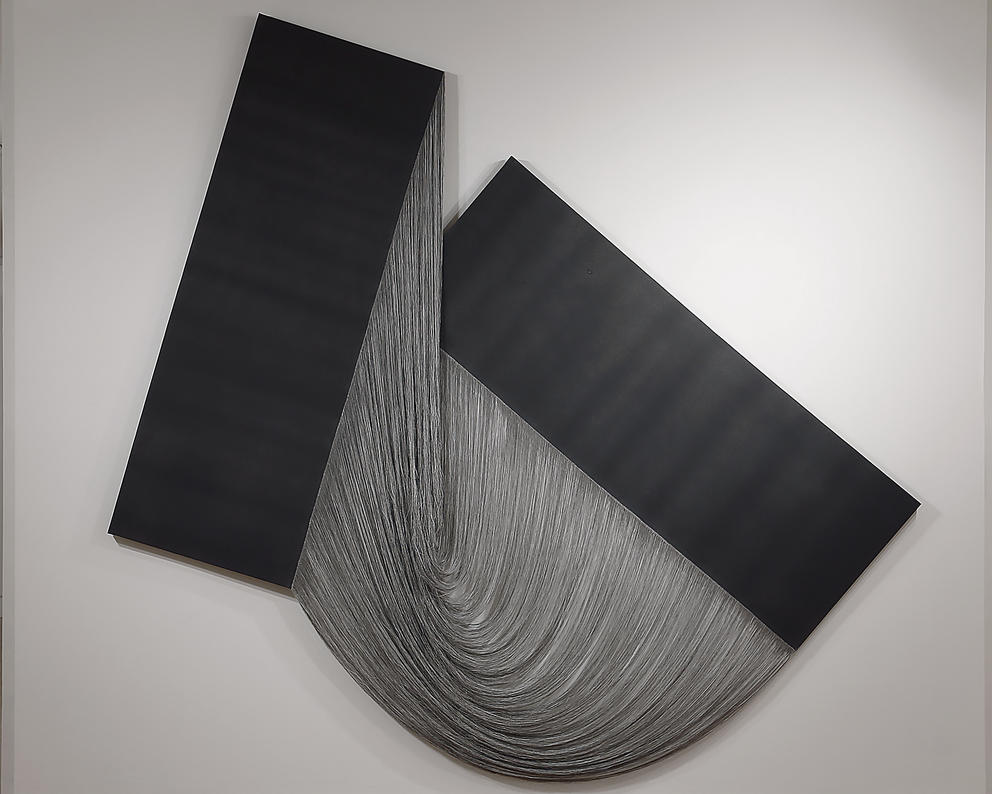

Multitudinous threads are also visible in Ko Kirk Yamahira’s Frye piece, “Untitled.” Yamahira offers another new take on painting by deconstructing the canvas itself. Using a painstaking method of unweaving the fibers, he morphs the blank canvas (here, painted black) into a sculpture. And since the once stiff canvas is now flexible, the work can be hung in any number of configurations — suggesting an art form that hinges less on canon and more on constant evolution.

And for one more Frye fave of mine, we return to Mary Ann Peters, whose piece in this show looks wholly different from her dragonfly installation at the Northgate station. Called “this trembling turf (the shallows),” the rectangular canvas at first looks like a soft and subtle sketch. Stepping closer, we again see a system of tiny threads — in this case, soft white ink marks covering the black clayboard. These hairlike whisps create a shifting pattern. I’d include a photo here, but it’s truly best seen in person.

Peters, who is second-generation Arab American, says the marks suggest hidden evidence of subjugated peoples. For her, the pattern — which seems to move as you walk around it — echoes the sound waves archaeologists use to find buried civilizations.

It takes many threads to weave a film festival, too, and we have a couple opening this weekend — with in-person screenings accessible via the Capitol Hill light rail station. As Crosscut contributor Misha Berson wrote last week, local art house theaters are finally starting to reopen their doors and welcome cinephiles into seats.

A good number of those seats are at the historic Egyptian Theater on Capitol Hill, which opened in 1915 as a Masonic Temple and is now operated by Seattle International Film Festival. SIFF kicks off its return to in-person shows with the inaugural DocFest (Sept. 30-Oct. 7), an enticing run of films, many of which are also screening online.

Consider: Becoming Cousteau, about the red-watchcap-wearing seafarer obsessed with life undersea; Flee, a gripping animated tale about a man who fled Afghanistan as a child and still remembers the journey with vivid emotion (in-person only, Oct. 1); The Hidden Life of Trees, based on Peter Wohlleben’s book about the forests as superorganisms; The Rescue, about saving the boys soccer team trapped in a Thailand cave; In Balanchine’s Classroom, about the groundbreaking choreographer who forever changed ballet — there is so much to see!

And the must-see list continues, as the 16th annual Tasveer South Asian Film Festival (Oct. 1-24) starts screening online and in person at the Broadway Performance Hall. Included in the slate are comedies (Coming Out with the Help of a Time Machine), a COVID relationship drama (7 Days), a coming-of-age dramedy (The Myth of the Good Girl) and a documentary about polyandry customs in the Lama mountain communities of Nepal (Co-Husband). That’s a lot of stops on the movie train.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.