Seattle artist Stacy Milrany created the miniature gallery in the vein of Little Free Libraries: a small box atop a post, with a clear glass door. In her many interviews, she has said she was hoping to bring a bit of art, joy and connection into people’s lives as the isolating pandemic stretches on. The F.L.A.G., as she calls it, is outfitted with little grooved shelves, an easel and a bench, plus rotating viewers in the form of plastic figurines. Everyone is invited to leave a piece of art and take a piece of art — and that happens several times a day (more often when it’s sunny).

ArtSea: Notes on Northwest Culture is Crosscut’s weekly arts & culture newsletter

I’ve been following the swiftly shifting inventory on the F.L.A.G. Instagram since it opened, and I have often wished I didn’t live on the opposite side of town. So many of the works are great, whether created by an established Seattle artist or by a crafty neighbor kid. Watercolors, encaustics, textiles, prints and photography — some are anonymous and some are signed … sometimes dubiously. When I visited last weekend, the gallery contained two abstract color fields, signed “Mark Rothko” on the back.

Two women came by while I was viewing. One took a faux Rothko, as the other deposited a piece that resembled a Matisse cut-out (signed with her real name, Miranda Bryant). I’ve had fakes on the brain since watching the new Netflix documentary Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art, which chronicles a notorious forgery scandal involving the revered Knoedler Gallery in New York City, and some 60 faked abstract paintings that passed as authentic works by Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, among others.

It brought to mind one of my favorite art films: F for Fake (streamable on Amazon Prime), Orson Welles’ 1974 documentary/film essay about infamous art forger Elmyr de Hory. I highly recommend this inventive movie, which Welles winds into a profound meditation on what counts as “authentic” art and who is considered a “real” artist and the overarching need for creation and connection.

Speaking of much-mimicked modernists, Seattle Art Museum just received a trove of monumental work gifted by Seattle collectors Richard E. Lang and Jane Lang Davis. The 19 pieces of abstract expressionism — worth millions — were created between 1945 and 1976, and include exemplary works by Francis Bacon, Willem de Kooning, Alberto Giacometti, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko (the real one, and not in miniature).

And, hallelujah, especially as we kick off Women’s History Month: the Lang collection also includes three important works by notable women: Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell — three of the five female abstract artists profiled in the book Ninth Street Women (which I raved about recently on Crosscut). “[These] soaring paintings … will allow us to put the achievements of female artists of this generation front and center,” noted SAM’s Catharina Manchanda in a press release.

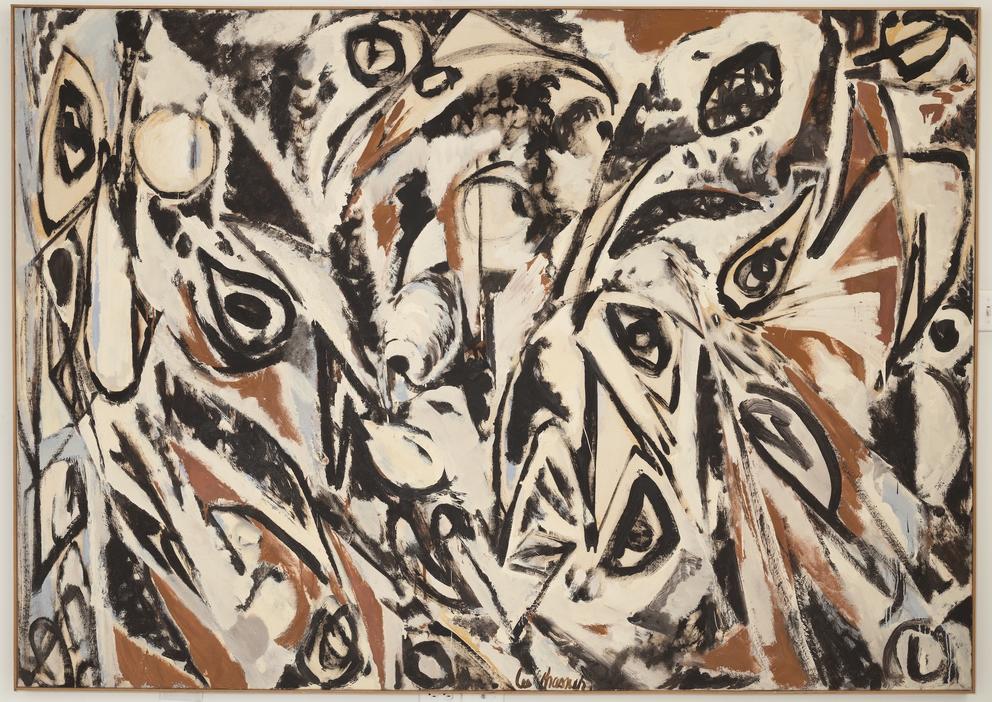

I’m particularly eager to see Krasner’s painting “Night Watch,” which she worked on in the darkest hours, during the bouts of insomnia she experienced while dealing with a variety of losses. The multitude of scattered and strained eyes seems to perfectly capture a familiar feeling of seeking without finding — whether in search of sleep, comfort or an end to extended unease.

An exhibit of the newly acquired works won’t go up until this fall, but a reminder that SAM reopens this weekend with big shows by two prominent Black artists from Seattle: Jacob Lawrence’s historical paintings, The American Struggle, and Barbara Earl Thomas’ stunning series of paper cut-outs, The Geography of Innocence. And there’s good news for antsy art lovers. A new study by the Berlin Institute of Technology suggests that museum going (at 25% capacity with masked staff and visitors) is the safest indoor activity during coronavirus — with less chance of transmission than supermarkets, restaurants or schools.

Wide-eyed insomnia is also the backstory of the short film And Then … by Seattle director Jenn Ravenna Tran, one of 123 films screening in the ninth annual Seattle Asian American Film Festival, in partnership with Northwest Film Forum (March 4-14; single films $8-10; passes $50-$120). Tran’s short film, about two women who meet and grow close during nighttime meanderings through Tokyo, is part of the festival’s LGBTQ showcase.

Other short film packages celebrate films from the Hawaiian, Southeast Asian, Japanese and Vietnamese diaspora. Plus: Short docs by local preservation group Vanishing Seattle, which profiles legendary Chinatown-International District spots Bush Garden and Four Seas/Dynasty Room, whose existence has been threatened by neighborhood development.

The centerpiece feature film is Seattle filmmaker Bao Tran’s much-anticipated kung fu comedy, The Paper Tigers, which I’ve been excited about since going behind the scenes for Crosscut in 2019. While the film has screened at online film festivals out of state, this is the first time it will be viewable by a Northwest audience (in Washington, Oregon and Idaho). It’s too late to catch the special screening at the Burien Drive-In (tickets sold out right away), but you can still stream it on the same night from home (March 6 at 7 p.m.)

Also rolling online this weekend, the Seattle Jewish Film Festival (March 4-18; single films $12-$20; passes $60-$180), “rezooming” for its 26th year. As usual, it’s a big, hearty spread of docs, feature films, comedies and dramas, with subjects ranging from Howie Mandel to African American rabbinical student Tamar Manasseh, from a Middle Eastern master chef to a Polish mathematician, from Soviet immigrants working as voice-dub actors to the Muslim members of the Israeli soccer team. So many distinct voices telling so many distinct stories — all in the name of making a human connection by way of art.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.