So Royon pivoted. In under two months, he put together an ambitious production and launched the company’s first ever documentary dance film. Nutcracker Suites invites viewers inside the 25-year-old organization for a behind-the-scenes look that features archival footage of past ECB Nutcracker performances, interviews with young dancers and video of new performances, all conducted under COVID-19 guidelines.

Royon’s determination is a fundamental lesson for ECB students, who on camera reveal that they’re learning more than pliés and tendus. In one scene, just before we see Mother Ginger’s Polichinelles pop out (wearing a new addition to their costumes: face masks) from under her ruffled crinoline hoop skirt, the film cuts to a young ballerina talking about her experience.

“It’s fun working with Mr. Benny because he pushes, and yet he’s really nice and kind to us,” she says. “I keep myself going by thinking about positive things like ‘I can do it and am able to push myself … to do more.’ ”

Nutcracker Suites (streaming Dec. 18-20 and Dec. 25-27) is a testament to the commitment Royon has for the company that, he says, gave him everything.

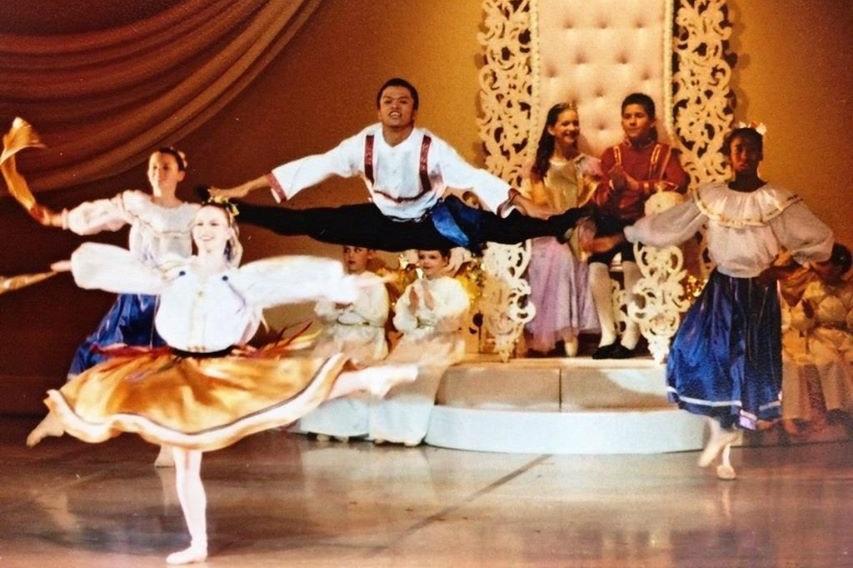

Originally from the Philippines, Royon immigrated to Auburn with his family when he was 12 years old. While studying at Auburn High School, he saw an ECB ad offering scholarships for young dancers. At age 16, with no previous ballet experience, he applied and attended his first ballet class wearing a T-shirt, stretchy pants and socks. Under the mentorship of Wade Walthall, Royon blossomed into his role as a dancer.

After graduating in 2006 from the prestigious Juilliard School with a bachelor’s of fine arts in dance, Royon went on to perform in productions with The Metropolitan Opera, including Madama Butterfly, Turandot and The First Emperor, and on Broadway in The King and I. After working with prominent choreographers, including Sidra Bell, Carolyn Dorfman and Karole Armitage, in 2010 Royon founded his own company, through which he has choreographed pieces for Ballet Hispánico and Atlanta Ballet.

Now 37, Royon is completing his first year as artistic director of the organization that gave him his first love of dance. “To me it’s work and it’s a way of life,” he says. “It’s my purpose.”

Crosscut spoke with Royon about Nutcracker Suites, Filipino Christmases and the life lessons that can be learned through dance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What was it about dance that helped you discover yourself?

Finding Evergreen City Ballet, and meeting our founding artistic director, Wade Walthall, my first ballet teacher — talk about a guy who you should look up to. Wade has danced amongst the greats. He danced in the age of Balanchine and Nureyev. He started late like me. He's inspired me. He lives and breathes and sweats dance. All the life lessons and conversations and times spent with him in the studio, I've used all of that not just as a dancer, but as a human being. It takes a lot of sacrifice and dedication, passion, consistency and resilience to achieve a professional career in dance.

Do you remember the first time you saw The Nutcracker?

One of my first experiences of film — believe it or not — was The Nutcracker, the movie that Pacific Northwest Ballet made [in 1986]. I saw that as a young kid — this is just now surfacing in my memory. I don’t remember how old I was, but Mr. Wade is in it. Funny enough, only after I left Evergreen City Ballet, was it brought to my attention that he played the Prince. I was dumbfounded.

Have you performed in The Nutcracker in a professional capacity?

All my Nutcracker experience has been pre-professional, at ECB. When I was starting out, I wanted to do “Flowers” [“Waltz of the Flowers”] and “Snow” [“Waltz of the Snowflakes”] so bad. One rehearsal Wade finally said, “Fine.” I remember floating and flying through space, running around with the girls, weaving in and out. But what you saw [were] young artists given an opportunity to plug in and connect to the idea of excellence, of doing their best where they are at. That's what Wade was really good at.

You brought some Filipino traditions to this Nutcracker. How does your Nutcracker differ from the version most commonly produced?

There hasn't been really huge changes, but the mere fact that I'm introducing an element from my culture is already big. For example, I introduce the parol, the traditional Filipino lantern that represents the Christmas holiday spirit in the Philippines. Aleksa Manila, a Filipino American Seattle drag performer, is reprising her role as Mother Ginger. These are small gestures of inclusivity. I look forward to expanding my choices when we have more time.

Is there a Filipino dance tradition or style you think could be incorporated?

That's something I'm kind of meditating on: What is a folk dance I could include in my own version of The Nutcracker? Tinikling is a dance with bamboo. It's very rhythmic, and it has Spanish influence in terms of the music. Another one called Maglalatik is a war dance using coconuts. The third one that’s good to know is Pandanggo Sa Ilaw. It really shows you what parts of our culture were heavily influenced by the Spaniards. I'm working on educating myself more on the indigenous sides of our dances. It's difficult because [with] colonization a lot of indigenous things disappear into the background. But there's a lot of younger generations now in the Philippines that are nursing them.

What should people know about Filipino Christmases?

Do you come from a big family? Imagine that times a hundred. And when do you decorate? We started in September. You have to go [to the Philippines] to understand how obsessed they are with Christmas.

How do your artistic director skills translate to making a documentary?

Initially, it was overwhelming. [But] there's just something about who I am. I just go for things. That comes with the way dance has taught me to keep trying, failure as part of the process. I've dabbled in dance film before, creating little music videos for my company in New York. So I'm familiar with it, but I had to learn. I had to think about how all these are interacting: the interviews, the archival footage, the recorded footage recorded this year. The focus was to tell our story in a new way.

Do you have any other experience with dance film?

In 2005, I was working for Mikhail Baryshnikov’s inaugural residency. He introduced the group of dancers to a film by DV8, called The Cost of Living. I fell in love. I was like, “Oh my gosh, we can actually enjoy dance on film.” I’m kind of an oldie. I like the traditional in-person in-theater experience. But there’s something about dance films that’s intriguing to me.

What are some of the creative opportunities that have come with the shift?

We're collaborating in new ways, and to be able to do that in this environment is an accomplishment in itself. For example, Bellevue Youth Symphony Orchestra. Typically in-person collaborations between music and dance are the go-to. But we had to find a new way to do this together. So there's a section in the film with a virtual orchestra pit [similar to a Zoom call] to accompany the “Waltz of the Flowers.”

Your choreography extends well beyond The Nutcracker. How would you describe your dance style?

When I immigrated here, it was a huge culture shock. I had to adapt and assimilate and embrace the American culture. My early years, I gravitated to the classic, European aesthetic ballet. As I grew older, I started to realize that my first connection to movement wasn't really ballet; my first was through Filipino folk dances. So my early years of choreographing were more contemporary ballet and modern, but where I am now, I'm really dissecting and integrating my culture back into my process. I would say my range would be from neoclassical, contemporary ballet, all the way to modern and avant-garde.

Tell me about your piece Land, Lost, Found, which premiered in October 2019 in New York City.

Land, Lost, Found was built out of that desire to root myself and find my beginnings. At that time, I was really sensitive to the social, economic, racial conversations [around] diversity and people of color. As I decolonize my experience, it dawned on me that I have to represent myself in my work. First of all, the three words “land, lost, found.” Unless you're Native American, this doesn't belong to you. I started meditating on what land means to me. Land as home, land as fertile ground. Lost: last year I felt lost. I felt like a lot of people were lost. And “found” is this future idea. We have to question our identity, reroute and find common ground. At the core of it was trying to make sense of the ever evolving spiritual and political landscape we live in.

You’re finishing your first year as artistic director. How did the pandemic impact your plans for ECB?

I believe that if we survive [this], there's nothing we can't do as an organization. That's why I don't have any reservations of why I am doing [Nutcracker Suites]. We're doing this out of necessity. We need this. The kids need this, families need this.

What do you hope the students take away from this production? And the audience?

That we can't take things for granted. It's all about the moment. And this is the moment we're in now. We're all trying our best at being compassionate to ourselves. Dance and ballet is such a hard place to learn because it is so demanding. That is why it is very important to still give [the students] some sort of semblance of structure. They've been emotionally, physically, spiritually stopped and displaced. What I'm telling them is stay lifted, keep your bodies moving, be inspired and look forward to a brighter future. And for the community, we're just trying to spread joy.

If you had to pick one artwork that encapsulates 2020, what would it be and why?

"The Scream," by Edvard Munch. I feel like that's what I look like every time I pivot, every time the news comes on. That's what we all look like. It's just so surreal and abstract and kind of confusing and dark. It's like, WTF.

Read more interviews in Crosscut's Art Pulse series.

A previous version of this story spelled the traditional Filipino lantern in Spanish as “farol.” The preferred spelling is “parol.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.