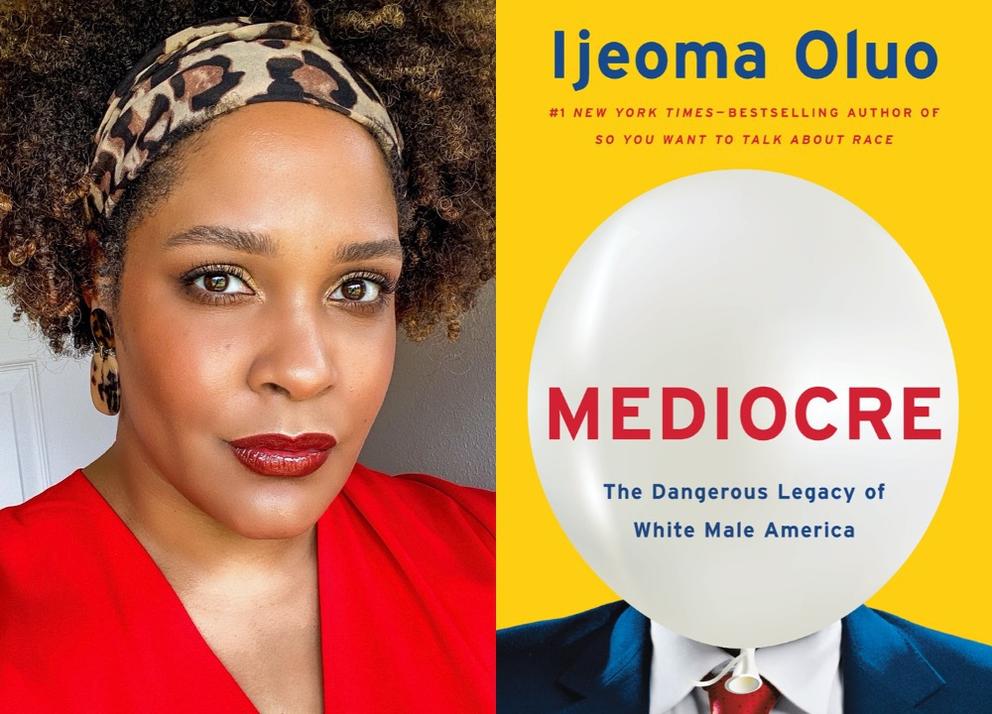

Now, Oluo is releasing a second book, Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America (Dec. 1, Seal Press). Where So You Want to Talk About Race was more of a practical introduction to racism and ways to talk about it, Mediocre presents a diagnostic of racism (and sexism) in America. Because, Oluo says, looking under the hood is the only way to finally fix the engine.

Her central thesis: Our society revolves around the preservation of white male power — skill or talent be damned. That’s actually dangerous, Oluo says. Particularly when “we’re willing to violently support the idea that people of no special talent deserve to run everything,” Oluo said during a recent phone interview. “Mediocrity at the head of our government can have disastrous consequences, especially in the violent ways in which we're willing to uphold it.”

Oluo is talking about U.S. presidents here, particularly the current one. But she’s quick to point out her book is not about Donald Trump. His presidency is merely, as she writes, “the predictable product of centuries of cultural, political, and economic conditioning.”

Oluo takes on many other white men, both historical and contemporary, from Buffalo Bill to Ammon and Ryan Bundy (in a chapter on the hypermasculinity of Manifest Destiny), Joe Biden (and his record on busing) to Bernie Sanders (and his bros), but also lesser-known names like “socialist feminists” Floyd Dell and Max Eastman, and segregationist National Football League team owner George Preston Marshall.

Constructed with the research of an academic essay, but delivered with the flair of a feisty Twitter thread, Oluo delves into a broad cross-section of topics, from post-Depression era labor politics to mass shooters, while dispelling the myth of American meritocracy. As she puts it in Mediocre: “We have, as a society, somehow convinced ourselves that we should be led by incompetent assholes.”

Crosscut caught up with Oluo to discuss her book, the 2020 election, how she stays optimistic amid so much pain and what she learned from Kurt Vonnegut.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In your book, President Trump is omnipresent, though you don’t dedicate a chapter to him. Was that a conscious choice?

Yes. This book was born out of the frustration that I think that many of us who write on issues of race and gender in this country, especially Black women, feel: this overfascination with angry white men as if they fell from the sky, and this overfascination with Trump as if he's the beginning and end of our problems — and the danger in that. Because it allows us to let our systems off the hook and let our ideals as a society off the hook.

I wanted people to see [Trump] as a part of the problem, as a part of the system, and to see where we participate in that system and have in the past.

If the Trump presidency wasn’t the beginning or end of our problems, how do you look at the 2020 election?

I think it was very, very important that Trump lose. We needed to send a collective message, however feeble it might be...But that refutation needed to be sent. It does matter to the young people coming up and looking to our leaders. It does matter to the collective consciousness and what we deem acceptable as a nation. But our systems are the same. It’s changed nothing about the work we need to do.

What this election has shown is how much harder it may or may not be. That's really what was at stake. The systems are much harder to change when the person in the highest office of the nation is loudly and proudly espousing racist and sexist and ableist and xenophobic policy. Then the work you have to do becomes that much more difficult.

All we're trying to do with elections, honestly to me, is to enable the change that we're doing on the streets.

You dedicate a separate chapter to Biden’s record on busing. What’s your take on the president-elect and what his presidency means for the nation moving forward?

Biden did get a chapter. Part of why I decided that both Biden and Bernie [Sanders] would was because I needed people to recognize the broadness of this problem and the different ways in which it can look.

I am grateful for what looks like will be a general return to some dedication to competency of the office, to knowing that as president, you're actually president of a whole country and not just the states that voted for you. That basic bare minimum. Once again, this idea of mediocrity: “Oh, yay. A president who believes that he's president of the whole country.”

But I look forward to holding this administration responsible for its actions and protesting the next president. [Like that] Reductress article that said: “I just want to hate the president a normal amount” [laughter].

It’s been a year where the weaponization of white womanhood, of “Karens,” has become apparent to many people in the shape of Amy Cooper and others. In the book, there's less focus on the ways in which white women have upheld white supremacy. Why is that?

What I wanted to look at were the power structures [and] how we uphold it. And the truth is that we all do in many ways.

What it comes down to in the end is white women recognizing that their best chance at power is their proximity to white men and white male power and how they can try to wield that for their own power grabs. What I want people to see is what they're aligned with. And this is what we’re aligned with.

As for white women, that’s a discussion that needs to be had. But as a Black woman, there's also a discussion that I could be having in the community right now about Black men and men of color and how they participate in these systems, where it can benefit them. About how as a cisgender Black woman I do. These are all really valid things that are their own topic in their own way.

Your book’s coming out at the tail end of a tough year. What was it like working on it during the pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests?

Really, really difficult. When I turn on the news, it's a pandemic that's killing Black people at a disproportionate rate. Black people are being murdered in the street. Young Black people are risking their health and safety to go out and protest for Black lives. And then when I sit down and turn the news off and do my work, I'm writing about [and] editing stories of violent white male supremacy. It was incredibly traumatic, honestly.

You live in Seattle, where we had CHOP and sizable protests. How do you look at the Black Lives Matter protests of this summer, particularly compared to a couple of years ago?

I don't think of it as compared to recent years, because it's a combination of what's been happening in recent years. It's the growth from protests that started in 2012 with the murder of Trayvon Martin. It's that generation — because generations are so short in the internet age — of activists, teaching young people what they learned in Ferguson in 2014 and 2016, and that’s beautiful.

That gives me hope. Even here in Seattle, finally getting some progress on the youth jail. Those are efforts I remember taking my kids to when they were small. What that means to me is that ... we can have growth and systems of resistance that can continue. And even when it seems like we didn't accomplish everything we wanted in 2012, in ’14, ’15, if we keep going, we keep that fire alive. We keep teaching and talking and know what our goals are; we can keep moving it forward.

So you think the protests have changed the consciousness, that more people understood something they didn’t before?

I do. What that means? We'll have to see. Being aware is only the very beginning. Knowing something isn't the same as doing something. Whether we continue to hold these elected officials accountable to the promises that they’ve made while we were protesting in the streets, we'll have to see. Whether we continue to have these conversations in our schools and our cities. But I've noticed, even in doing this work, a shift in the conversations. I'm no longer asked to come speak at an organization and explain what racism is. I'm no longer being asked to defend the idea that it exists. I'm being asked: “What can we do?” And that is a shift.

That reminds me of what you said about “hating the president for normal things”: the bare minimum, incremental change.

There’s something important I need to explain about this work: I am not fighting to create a kinder, gentler white America. I'm fighting for Black lives. I'm fighting for the lives and the dignity of people of color in this country. And what that means is that it's never enough, but every life saved matters.

And yeah, absolutely, it’s pathetic that 400 years into this system, we’re like: “Woohoo, I don't have to explain that [racism] exists anymore.” But also, that means the people on the ground trying to do the work don't have to spend a year explaining that it exists. We can actually maybe get to a policy or two that can change someone's life. And those lives all matter.

On top of everything this year, your house was also destroyed in a fire. How are you doing now?

Our house caught fire and, the next day, my son calls from college to say he had COVID. It’s been a lot. Maybe I'm annoyingly optimistic, but that was another reminder of what community means, the outpouring of support and love that kept us going and recognizing how fortunate we are.

My son’s recovering. We have a roof over our heads. We came out without shoes, but we came out with our lives and with a community that loves us. I like to say we are incredibly fortunate people in a really unlucky year.

Speaking of your optimism: A recurring theme in this book is the fact that white male mediocrity is itself a recurring theme throughout history. How do you stay hopeful that things will change?

This is a roundabout way of answering, but when I was a kid, my favorite author was Kurt Vonnegut. I didn't realize until I started reading him that it was OK to believe that human beings could be wonderful, and to be perpetually heartbroken at how they refuse to be. I try to write from that space. I've seen what people can do. And so I write because I am heartbroken and disappointed at the ways in which we try to find a reason to not do it. But I know we can, and I just refuse to give up hope that we will.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.