“Because I love them and know how much they love to be dirty I will hook them up to saline drips with glucose and allow the mushrooms to grow in the recesses of their body,” the mother says.

Is this how the mother perceives the world she’s protecting her children from? Is mom just a germaphobe? Does the black mold represent something else, something bigger and deeper that she can’t control: aging? Time passing? Loss of innocence? Or is the world really just that weird?

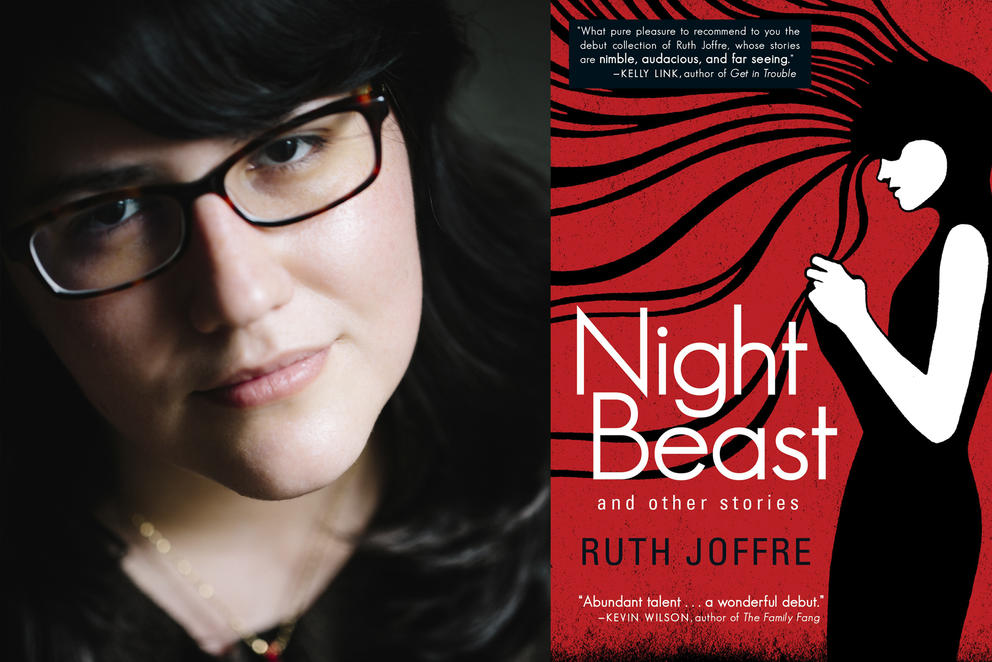

In her stories, Joffre presents scenarios where broad “what ifs” become more than a possibility and lead the reader to the next question: “now what?” She captures the complexity of being a human, taking inspiration from magical realism, fabulism, speculative fiction and sci-fi — writing as a genre shape shifter. Joffre, 30, moved from Iowa to Seattle in 2014 and is now based on Capitol Hill, where she has been a Hugo House teacher for the past five years. The literary center recently announced she will be the new prose writer-in-residence, beginning Sept. 15.

In her new role, Joffre, who graduated with an master’s of fine arts from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, will continue teaching classes at Hugo House, help community members with their manuscripts and work on her upcoming book of flash fiction shorts, A Girl Walks on the Moon and Other Stories. She’ll also be in charge of organizing community events, something she’s done before with Fight For Our Lives, a recurring literary series that showcases writers from marginalized communities and raises money for different causes.

Crosscut caught up with Joffre to talk about her new book, the blurred lines between speculative fiction vs. magical realism and how different story forms can capture both the danger and wonders that come with being a queer, Latinx girl.

The underlying themes of your stories are kind of tragic, kind of mysterious. What’s the emotional lens you are trying to get readers to tap in to?

Most of my work falls under, like, lesbian nightmares. I want them to be kind of sad and dark and confused. And also maybe in love.

Your short stories jump between genres and styles. Is there a common thread among all of them? What are you trying to get people to see?

What I want people to see is that there is so much going on under the surface of everything, of interactions. Even when somebody has no facial expression and doesn't appear to be reacting, there's so much going on. A lot of it is trying to incite empathy, to incite understanding, too. I feel like sometimes people aren't willing to go to a place and they don't want to feel it. They refuse to believe that it exists or that it could happen to them. I try to write stories that are very open to the uncomfortable parts of human experience — the dangers that we face as people in underrepresented groups, minority groups. And the dangers of vulnerability within relationships and how those can go wrong or how they can go right and still hurt.

What was your girlhood like? And how does it show up in your in-progress book A Girl Walks on the Moon and Other Stories?

For me — and for I'm assuming a lot of people — girlhood is not as safe a space as one might like it to be. It's a very complicated space in a lot of ways. It's a very dangerous space in a lot of ways. Nobody in America is using “girl” in a positive way. It has this belittling sort of negative tone. Part of this is to reclaim and explore that, and what it actually means for people of all walks of life.

I had a very complicated childhood partly because [I’m] the daughter of immigrants on one side of the family and then part from this white Army brat background. Very competing cultures. We were very poor for a lot of my childhood. So coming from this place of not having a lot of privilege and then on top of that, a lot of economic privilege, on top of that being a Latinx, then coming out as queer and being fat. Having this intersection of identities that is like: Nobody cares about you, but other people like you. That's how it feels a lot of the time in America.

So [writing the book is] to be able to write stories that speak to that dynamic, but also find the beauty in all of these identities and show people that being a girl doesn't mean just one thing. It is not a pejorative. It is this beautiful place of wonder and possibility that has been made very dangerous and unsafe because of all of these cultural and societal pressures.

Why are you using different writing styles in your forthcoming book?

I think approaching it through different angles adds to the richness. You get different facets of the problem when you approach it through these different tools and techniques. I think it's also just more exciting for the reader.

I want to make sure that I'm switching it up enough that my readers feel like they're reading something really original. I want it to be a very varied experience overall, not just for the readers, but for me.

Where do you feel your stories come bubbling up from?

I've said before a lot of it is queer sadness. A lot of it is being in love and wanting to explore the complexities of that. It's an intersection of a lot of things. A recent example: I was doing a quick writing exercise with some friends.… I had just watched this video about a new burial process, freeze drying a corpse and reducing it to ash. That all kind of intersected with my experience as a girl from a Latinx family. Now I'm writing this story about a girl whose grandmother was composted.

Does your Bolivian heritage often influence your writing?

It does more now than it used to. I’m half Bolivian and the other half of my family is white — that mixed white ethnicity where you're not sure if you're part Swedish, it's all a blur of whiteness. A lot of my experience growing up was white passing. My mom didn't really want to teach me that much Spanish and didn’t introduce me to a lot of the culture. I think that's very common for first generation immigrants and the children of immigrants. It's been a long process of reconnecting with that culture and that heritage through my family, through reading, through whatever media I can find about Bolivia. It took longer to weave its way into my work than some of the other parts of my identity — for instance, my queerness, which was very present in my work from the beginning.

Is there a connection between Latin American storytelling traditions, such as magical realism, and your own storytelling?

There's a lot of confusion about what magical realism is now. And it's getting co-opted a lot. I'm very careful about when I use that term and draw from that tradition. I think most of my work would actually fall into fabulism. There's something that I’m working on, which is a much longer project, that I would really link to magical realism. I'm reading a lot of Gabriel Garcia Marquez right now and Isabelle Allende to try and get into that space and tap into that tradition. Most of my short fiction ties more to that more speculative, fabulist, tradition.

Do you see speculative fiction as a similar way of telling stories?

There's a lot of debate and room for interpretation. It's super blurry. There's stuff that I've written that you could call magical realism and you can call it fabulism. There are a lot of similarities in the traditions and the techniques and the elements. I'm getting more into speculative fiction from Latin America, which is distinct from American speculative fiction, the same way that African speculative fiction and sci-fi is distinct. I'm not the expert on any of those, but those traditions borrow from each other, and they're really fascinating to learn about.

Which style comes most naturally for you?

Right now, speculative stories make the most sense to me because they're so full of wonder and possibility and imagination. You get to point out what's wrong with the world and reflect so many of society's problems, but you also come up with solutions and empowering situations, and imagine worlds where the queer character doesn’t die like at the end of every TV show. Before, during my MFA and undergrad, realist and realism was what I was primarily doing. I wouldn't say that it necessarily came naturally, but it was the only thing that seemed like it was doable or respectable, until I had some professors that were actually interested in sci-fi and I was like, “Oh wait, I can do this like for a career?”