A large-scale reproduction of the sculpture — an abstract body with arms upstretched — stands on the Space Needle grounds. Visitors can see how “The Feminine One” inspired the struts of the structure, designed to resemble three figures standing back to back, legs apart and arms raised, holding the flying saucer shape above.

But Bullert's new documentary goes further, asking whether the feminine one in question might be a specific woman — a prominent dancer from 1930s Seattle.

The short film, Space Needle: A Hidden History, will have its world premiere at Bumbershoot this weekend as part of SIFF’s programming. In it, Bullert, who also teaches at Antioch University in Seattle, interviews Space Needle experts and Seattle historians — including Steinbrueck’s son Peter — about the inspiration behind our city’s architectural icon.

Thanks to a previous film she made for a Space Needle anniversary (Space Needle at 40), Bullert had a sense of the building’s history when she began this project. She knew Steinbrueck and the sculptor Lemon were connected with the tightly knit, thriving arts community clustered around Cornish College of the Arts in the 1930s and ’40s.

Since “The Feminine One” is clearly based on a body in motion, she says, “I started nosing around to find out who were the prominent female dancers at Cornish during that time.” That’s when she first encountered the name Syvilla Fort.

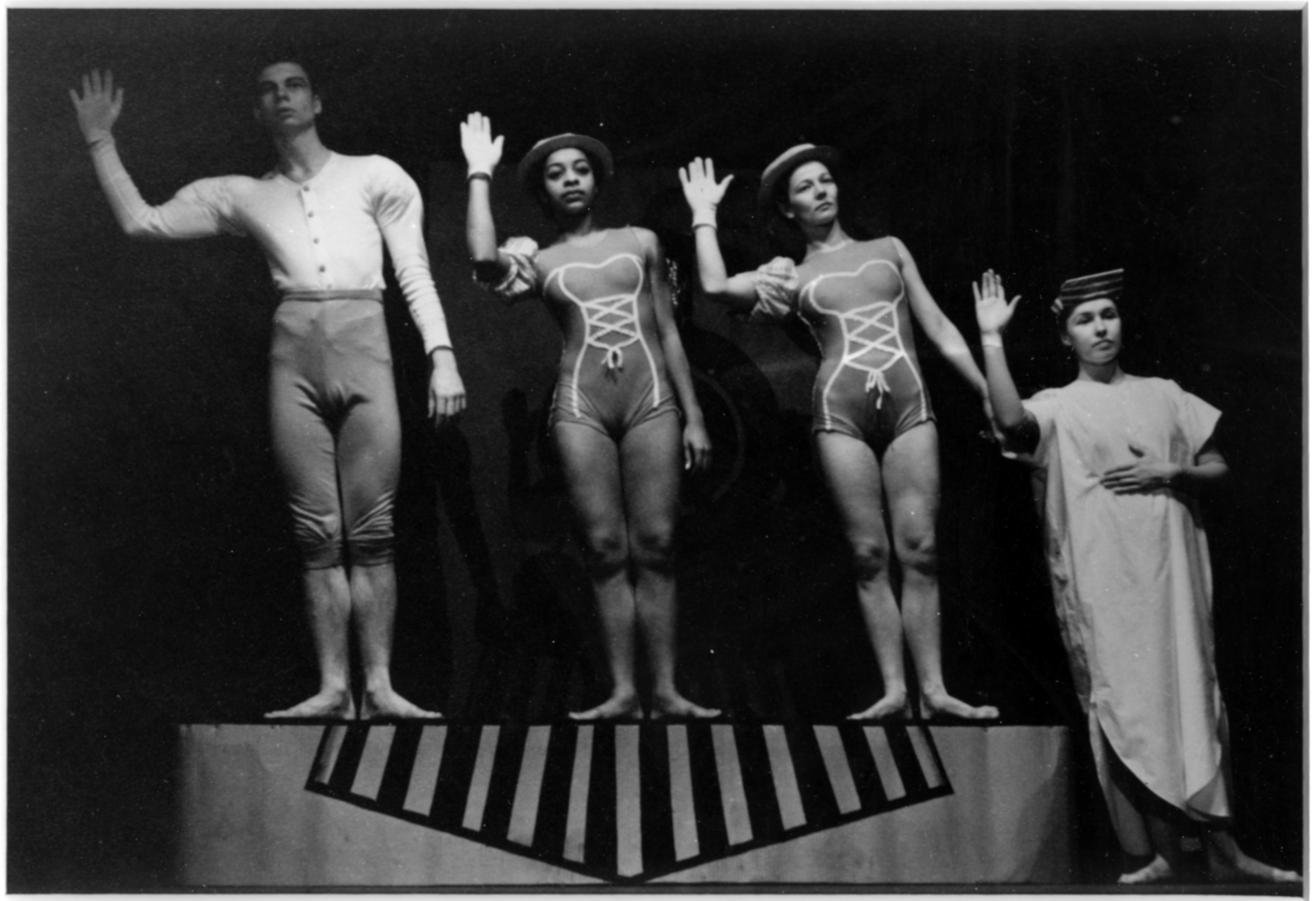

Syvilla Fort was born in Seattle in 1917. As a child, she longed to take ballet classes but was denied admission to ballet schools because she was Black. Her parents secured private tutoring and, after graduating from Roosevelt High School in 1932, she enrolled at Cornish as one of the college’s first Black students.

It was there, during the 1930s, that she started making work with members of Seattle’s burgeoning arts scene.

Fort danced with Merce Cunningham and developed her own “Afro-modern” style. In 1940 she choreographed two dance pieces for which she asked John Cage to write accompanying music. One of the works, “Bachannale,” inspired Cage to invent his very first “prepared piano,” initiating his legendary innovation.

She went on to pursue dance in Los Angeles, toured with “matriarch of Black dance” Katherine Dunham, and landed in New York City, where she gained acclaim for teaching movie stars how to dance for roles — including James Dean, Marlon Brando, Eartha Kitt, Jane Fonda and Chita Rivera. She was toasted by Harry Belafonte, James Baldwin and former student Alvin Ailey.

When she died of breast cancer in 1975, the New York Times called her a “pioneer in Black dance.”

Though her name has been largely overlooked, Fort was a big deal in her day. And she most certainly would’ve been known among the artistic crowd that included Lemon and Steinbrueck. Did she inspire the streamlined sculpture that later inspired the anchor of the Seattle skyline?

“It’s a speculation,” says Bullert. “You can never really get to the source of artistic expression, but the point is to look at the circumstances. I want to invite people to reimagine the Space Needle. Because now I see it as a beacon of women’s empowerment.”

Bullert’s film makes a compelling case for at least considering the possibilities. And her hypothesis becomes even stronger when we learn a striking bit of family history from Peter Steinbrueck: In the film he says his mother told him that before she and his father met, his father had a romantic relationship with Fort.

It’s impossible to know for certain whether Fort was indeed “The Feminine One,” but Bullert stresses that hers isn’t a traditional documentary. “In a sense, I’m projecting meaning onto the building,” she says. “And then it pivots into its own piece of art.”

After the talking heads subside, the film transforms into a melange of poetry, dance and music — all created by Black women.

Bullert invited Jourdan Imani Keith, who earlier this month was named Seattle’s Civic Poet, to write a poem imagining the Space Needle as a woman, perhaps specifically Syvilla Fort. Like most contemporary Seattleites, Keith had never heard of Fort before.

“It was not a surprise to realize this hugely influential woman was someone many people had not heard of, because that is often the case with female artists,” Keith says, “doubly so if that female artist is also of African descent.” She says when she learned about Fort’s history she was reminded of Nina Simone, who wanted to be a classical pianist, but was not allowed such schooling because of her race.

In the film, as Keith reads her poem (...my leap of legs in concrete / a grand plié at night) local dancer Nia-Amina Minor, of Spectrum Dance Theater, performs an original piece inspired by the poem, the building’s history and the idea of the Space Needle as a woman.

The accompanying music was written and performed by Seattle cellist Gretchen Yanover. These creative acts — including the film itself — combine to resurrect Fort’s name and artistic legacy, and spark an intriguing mystery embedded in the Seattle landscape.

“Nobody has said this is hogwash yet,” Bullert says. “They certainly could.” But she reiterates that her film is a work of speculation. “It’s also a way to revive Syvilla Fort — to shed light on that piece of Seattle history.”

Keith says the idea that Fort could’ve influenced the design seems possible. “The Space Needle has always seemed quite female to me — it certainly has the spirit of a dancer,” she says.

Has learning about Fort’s history changed the way she sees the Seattle landmark? “Now I see the power of Black female persistence,” Keith says. “It makes me think of the ballerina who was not allowed to be, but who became a dancer anyway and taught so many others.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.