Baker’s source material for the exhibit is archival Senate documents chronicling the 1841 slave revolt on the brig Creole. It was the only successful large-scale rebellion by U.S.-born enslaved people — a momentous event in American annals, but one most citizens never learned about in school. This too, has been largely erased. But the facts remain: The Creole was transporting a human cargo of 135 people from Virginia to Louisiana when an enslaved cook named Madison Washington led a mutiny that forced the ship to land in the Bahamas, a British colony, where slavery had already been abolished. As a result, 128 enslaved people gained their freedom.

“The entire project is about survival,” Baker says. “What it means to someone’s internal landscape to survive, what kind of rigor that requires.” He’s not just talking about physical fortitude. He’s referring to a mindset that is passed on for generations. “Survival transfigures what joy feels like — what anything feels like — it changes the terrain,” he says.

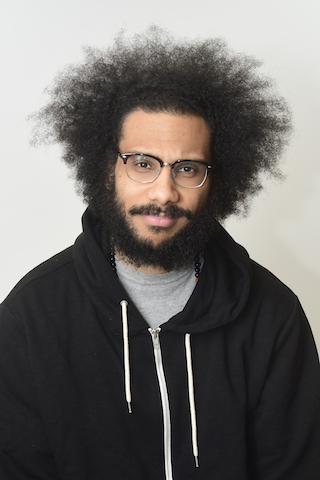

Tall and long-limbed, Baker has a low, mellifluous voice tailor-made for the many poetry readings he does around Seattle (as well as his early stint as a rapper). He’s scholarly, funny and a bit shy, a reader and retainer of history, which he pulls into the present with his musical verse. Born in Seattle to a Jewish-Polish mother and Black “country boy” father, he earned his MFA in poetry from the University of Southern Maine and published an acclaimed book of poetry, This Glittering Republic, upon returning to his hometown.

“The psychic landscape of this city — the way its profound wealth collides with its moral failings — influenced me,” he says. “Growing up here made me want to do the opposite. If I encountered the lost, forgotten stories I’d do everything possible to call them forward.” Whether writing about baseball players in the Negro League, Sarah Baartman (the “Hottentot Venus”), or the youngest person executed by electric chair in America, Baker’s poems are about the “afterlife” of slavery.

“It’s easy to focus on gaining freedom, but it’s so profoundly inadequate,” he says. “You might escape slavery but you can’t escape the social construction of anti-Blackness, or how it prefigures your position in the world.”

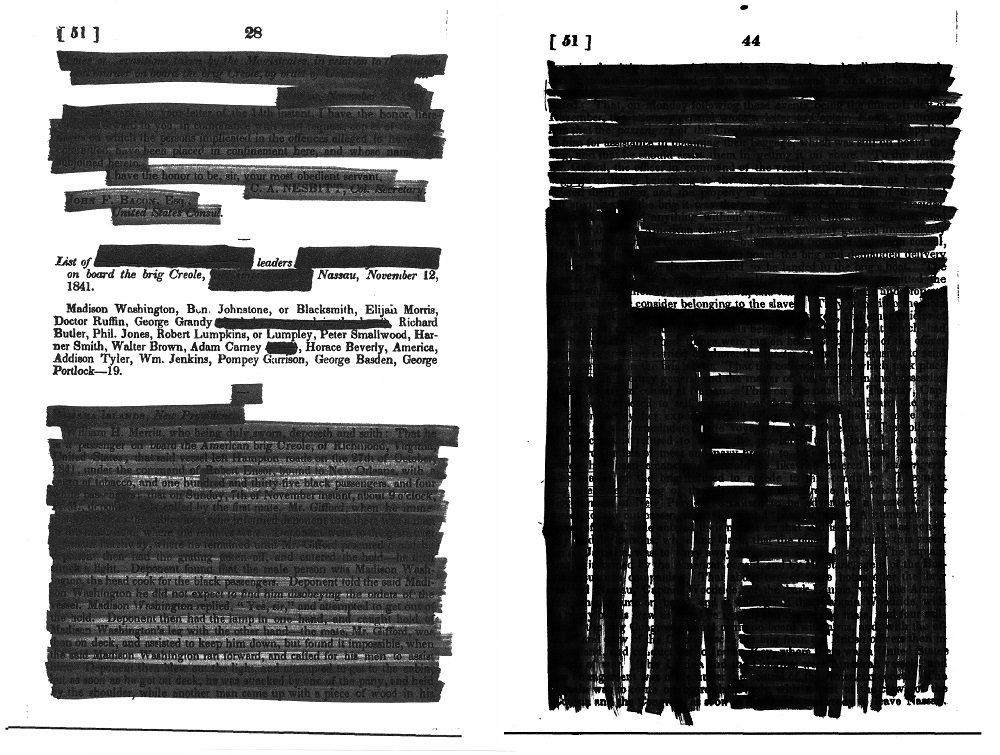

Ballast is part of a long-term project in which Baker has been immersed since he learned about the Creole in 2015. As a history buff, he was surprised he’d never heard of the event and embarked upon a massive research project. The poems in Ballast are part of a forthcoming book of erasures and “invented form” poems (the latter can be read in any direction) chronicling the revolt in the imagined voices of Creole passengers. In 2016, he won the James W. Ray Venture Project Award, which led to this innovative show of poetry at the Frye.

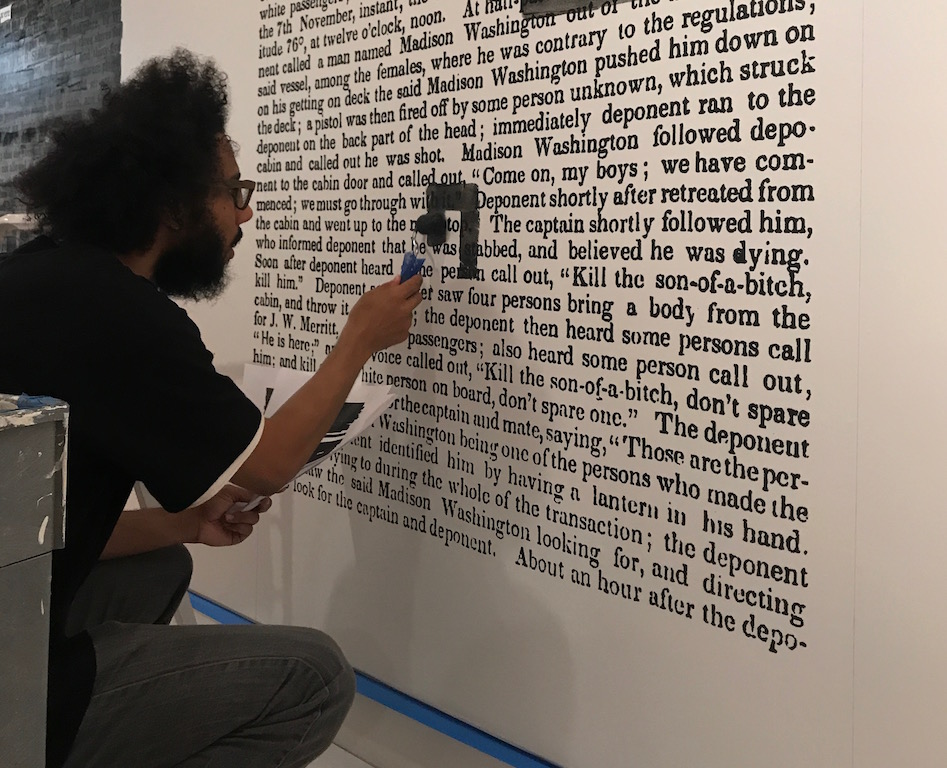

“For me, it’s about recovering language,” he says, of Ballast. “The lost language of a Black interior that’s not respected or even visible.” With the erasures, he covers up text to uncover untold stories hiding within; he blackens the white voices of the Creole crew (the only people allowed to give testimony for the historical record). “I can’t recover the speech from the enslaved people involved,” Baker says, “but perhaps an aspect of what they might’ve said.”

On the museum walls, their voices emerge like ghosts from the inky morass: “I am a crisis arrived.” “A cargo of alarm.” “Answer me.”

Baker has already completed 50-some erasures based on 44 pages of Senate documents, but the gallery work feels entirely new, and not just because he’s using a small paint roller instead of a big Sharpie. “The act of redacting on this scale has been a much different experience,” he says. “I know these poems, I know this text, but I found myself getting lost. The words aren’t where I remember them.”

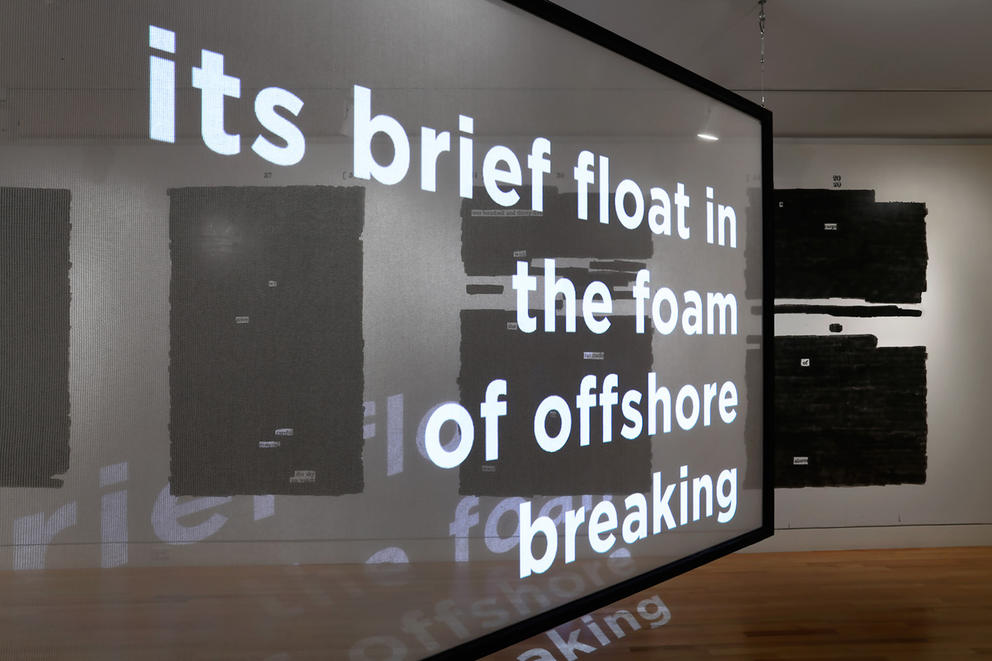

Adding to his sense of being at sea in his own language are two oversized screens, hung at different angles mid-gallery, onto which are projected Baker’s invented form poems. Short bursts of text (“gilded by a filigreed absence,” “hidden within midnight’s unctuous gristle”) pop up and bleed through the translucent fabric onto the floor, walls and visitors. Just as you grasp the language, it disappears. On the backside of the screens, the letters appear in reverse (“it looks Cyrillic to me,” Baker says). Your brain automatically tries to grok the backward sentences, but can’t quite make them out, much like the script on the enlarged, faded copy of the ship’s manifest on display.

The white screens hanging like sails, the thick horizontal redaction lines like the boards of a wooden hull, the flashes of words like lightning, the multitude of voices — the physical space conjures a ship that, no matter how much ballast is added, cannot be righted.

Tying mooring lines across time and space, Baker reveals how we are still living with the “after effects of slavery,” even in this place far from the Confederate South. Working for Plymouth Housing as his day job, he says, keeps him “well-acquainted” with the living legacy. “This city has always had the means to offer redress to its citizens for the way it was constructed,” he says, outlining a shape with his hands that suggests redlining. “But we don’t press for that, we don’t elect people who prioritize that.”

Asked if Ballast is more about making a contemporary point or illuminating history, Baker says, “Those are the same thing.” He sees a straight line from surviving slavery to the everyday coping mechanisms African Americans employ in a still unequal, still unjust society. “The ways in which Black folks live and create under constraint — that’s always relevant to me.”

Crosscut arts coverage is made possible with support from Shari D. Behnke.