Nevertheless, the topic of masks and wearing them is still hotly debated, often in retail chains as iPhone cameras roll. These videos have prompted questions: Was there resistance to masks during the 1918 pandemic? Did they work? How was mask wearing enforced in the old days?

Quick answers: Yes, there was resistance and defiance, masks worked to limit or stall the spread of disease, and mask-wearing was sometimes enforced with fines, arrests, jail time and, in at least one case, gunfire.

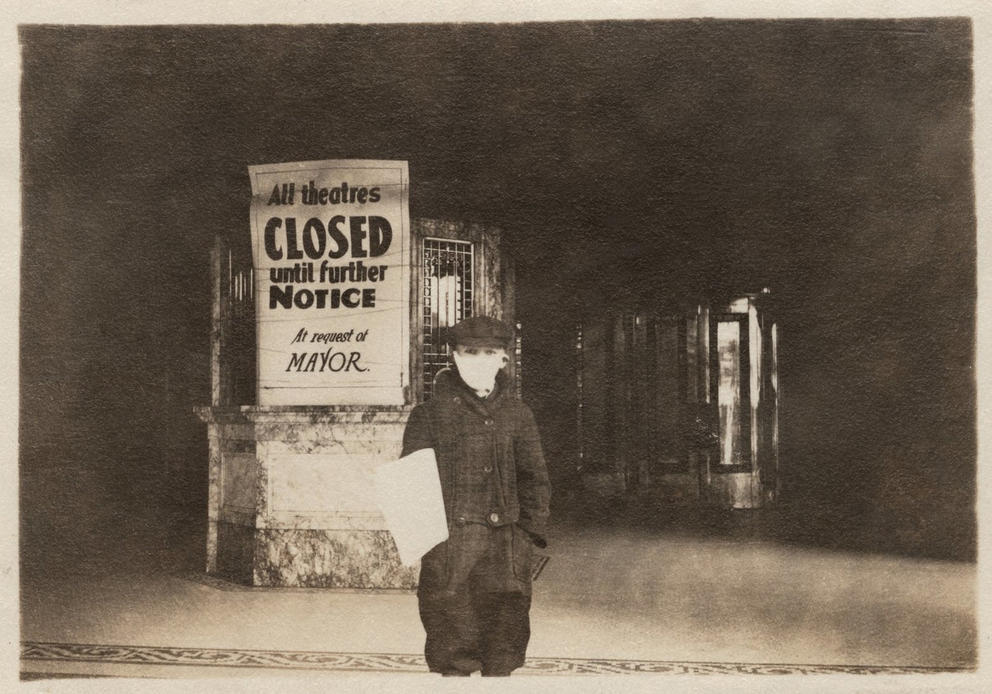

After scouring press coverage on the West Coast during the 1918 flu era, I can say resistance to adopting masks was not universal, but it also was not uncommon. In Seattle, during the influenza’s lockdown period in October and November of 1918, people without masks were banned from public transit and ticketed or fined by members of the police's masked “Flu Squad.” Headlines had a somewhat negative spin: “Thousands Are Hit with Flu Mask Order,” shouted one in the Seattle Star.

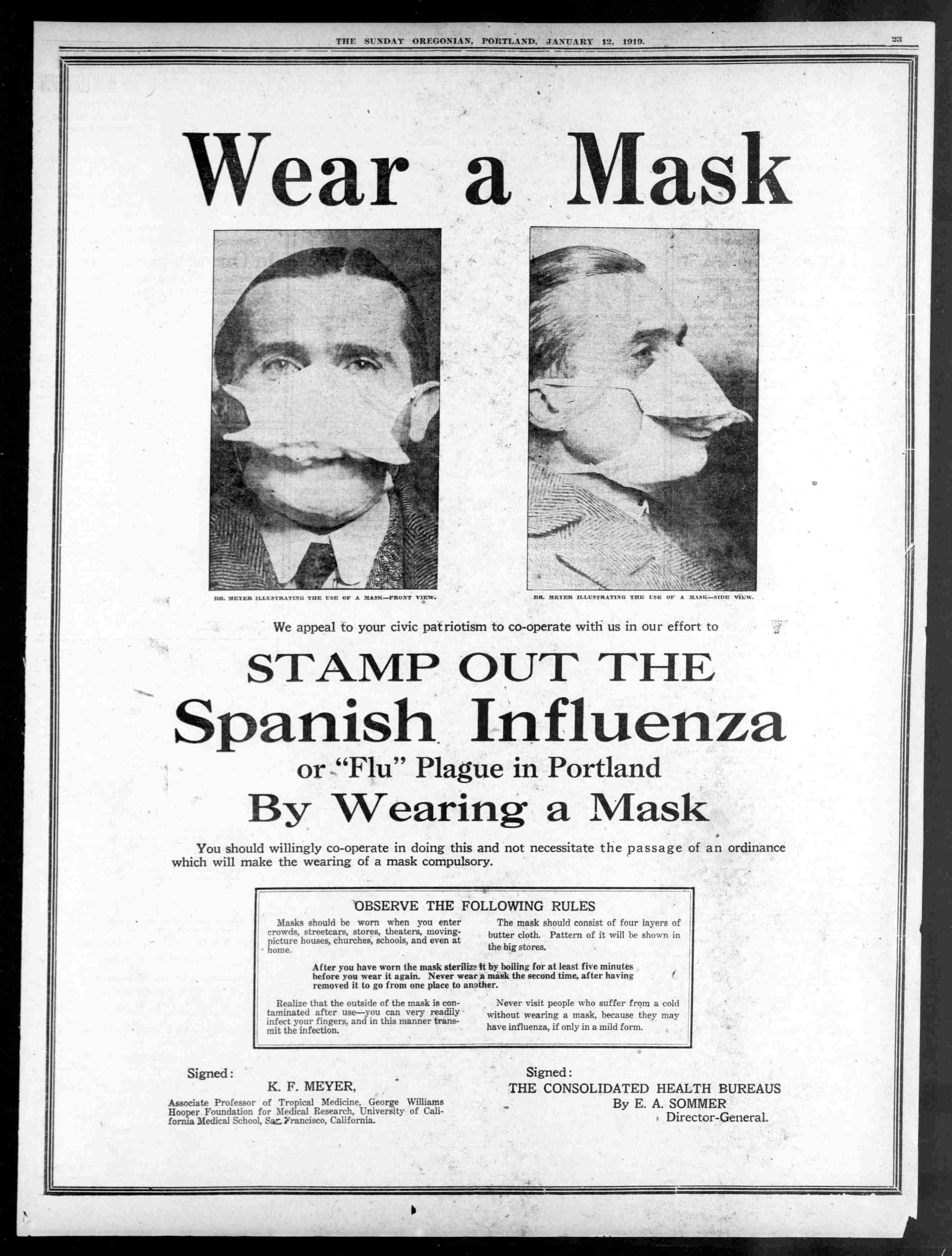

The masks recommended during the 1918 pandemic were made of heavy-duty six-ply cotton gauze. They were thick and no particular joy to wear. People who refused to wear them or couldn’t be bothered were called “mask slackers” or “mask scoffers.” During World War I, the term slacker described people who neglected their patriotic duty, almost as bad as being a draft dodger.

In Walla Walla, the chief of police, John Haven, refused to enforce a state mask mandate. He pointed out that he was going to meet heavy resistance and, anyway, that he had no authority to carry out a state directive, only city ordinances. Still, he also openly defied the instructions of the city’s health officer, J.E. Vanderpool, to follow the state health officer’s guidance.

Even as people dropped dead in Walla Walla and rural southeast Washington, business owners pushed to have their establishments — saloons and billiard halls — reopened in defiance of advice from most doctors and health officials. The Walla Walla police chief’s determination not to enforce a state edict is mirrored today by a number of sheriffs in rural Washington who have said they will not enforce Gov. Jay Inslee’s mask requirements. The sheriff of modern-day Lewis County told his people, “Don’t be a sheep.”

Yakima was less reluctant to crack down on scoffers and slackers if they were doing business with the public. The city's sanitation inspector arrested 15 people for “working or transacting business in a public place without wearing gauze masks prescribed by the city health commissioner,” according to a 1918 article in the Spokesman-Review. The problem was the merchants, not their customers. The business community held that the city had no authority to mandate masks.

Then, as now, health officials were divided on whether masks truly prevented the spread of Spanish influenza. Many understood that the chances of transmission were worse in enclosed public spaces, like churches and movie theaters, but opinion was divided on the efficacy of masks outdoors. Some believed the fresh air fought the flu, and encouraged people to open their windows and let in the bountiful breeze.

Mainstream medical belief held that going maskless could spread contagion. The thick multilayered gauze masks appeared to work in reducing new cases, and they proved effective for medical staff treating flu patients.

Other physicians claimed the masks themselves became an unsanitary health hazard if not cleaned and sterilized. Dr. J. C. Bainbridge, a prominent physician from Santa Barbara, California, claimed, “The common use of the mask tends to propagate rather than check influenza.” Others simply argued that masks had no effect. However, historians generally believe that social distancing and masks saved tens of thousands of lives since there was little else that proved truly effective, such as vaccines and serums.

Still, divided opinions and often localized health authority meant communities responded differently to the pandemic. Seattle and Spokane, for example, were generally mask compliant. Spokane, in fact, had trouble keeping up with the public demand for masks, and many of the coverings were hurriedly made and ill-fitting. The Spokesman-Review featured photographs of professional women in masks under the headline, “Women in Business Life Don ‘Flu’ Masks.” There was less enthusiasm in Portland, on the other hand, which did not pass a mask ordinance, with one city council member objecting that he would “not be muzzled with a mask like a hydrophobia dog.”

The San Francisco Bay Area saw reluctant acceptance of masks at first, then massive pushback. A mandatory ordinance, announced in bold headlines on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle in late October 1918, read: “Wear Your Mask! Commands Drastic New Ordinance.” It blared over the mugshots of city leaders all masked up like surgeons. Many equated mask compliance with patriotism and the war effort, an appeal that worked for many prior to the end of World War I with the signing of the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, midpandemic on the West Coast.

In the debate over masks by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, Seattle and Portland were cited as cities that had benefited from masking. Violators of the new San Francisco law would be guilty of a misdemeanor and fined between $5 and $100 and risked up to 10 days in jail. The city wasn’t fooling. By Nov. 10, a San Francisco Examiner headline read, “1,000 Alleged Mask Slacker Cases in Jails.” Judges tried to clear this mass of mask arrest cases as fast as possible with fines or two days in jail.

But the penalty, in some cases, could be even worse. Shortly after the mask rule went into effect, a local blacksmith named James Weisser was arrested for drunkenness and spent the night in jail. After release the next morning, he proceeded to publicly and loudly inveigh against the mask rule on the corner of Powell and Market streets, drawing a substantial crowd, according to the Examiner newspaper. This intersection is well known as the downtown jumping-off point of the city’s famed cable cars.

A deputy health inspector, Henry Miller, pushed his way through the crowd and ordered Weisser to get a mask at a nearby drugstore. Weisser then attacked Miller, flogging him with a pouch full of silver dollars and knocking him to the ground, where he continued the beating. Miller drew and fired his revolver, wounding Weisser and two bystanders, including a woman whose leg was grazed by a bullet. The crowd scattered and police arrested both Weisser and Miller. I could not find coverage of what happened to the two after that.

The city’s influenza numbers showed improvement less than three weeks after the mask ordinance went into effect. But, as in the current pandemic, opposite conclusions were drawn: Success could mean masks were no longer necessary, or could be a sign that the policy was working and should continue. That December, the mask order was lifted. Bay Area residents celebrated. In Oakland, one newspaper reported, “citizens made bonfires of their muzzles in the streets.”

But shortly after the mask bonfires, the Spanish flu reignited and cases climbed again. San Francisco reinstituted its mask rules in January 1919, triggering a rebellion that resulted in the formation of the Anti-Mask League. A mass meeting protesting the masks drew over 2,000 people. The league petitioned the city, demanding a rollback of the mask mandate, and officials complied a month later.

In Seattle, a similar narrative took hold. Once people were free of their masks, they refused to go back to them, even as flu cases started to rise again. A Seattle Post-Intelligencer editorial in early December 1918 warned that reinstating health edicts would spark fear not of the flu, but of an excess of “regulatory zeal.” There was no indication, the editorial opined, that “another shutdown of business and revival of the mask would be tolerated.” Compliant Seattle was done with compliance.

Many observers of the time believed masks helped flatten the pandemic curve. When it came to stifling dissent, however, they proved an ineffective muzzle.