BJ Cummings founded the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition in 2001 — the same year that the river was listed as a Superfund site in need of cleanup. Cummings’ new book, The River That Made Seattle: A Human and Natural History of the Duwamish, chronicles the history of the river and the people whose lives have been intertwined with it. The book is being published by the University of Washington Press on July 11, 2020. Cummings will be hosting a virtual book launch from the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center on July 11, and other events in the following weeks.

Crosscut emerging journalist fellow Mandy Godwin recently met Cummings on the banks of the Duwamish for a Q&A discussion about history, industry and environmental racism.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I’d love to hear about your vision for the book.

I felt I had to write it because I had already spent 20 years trying to clean up and restore this river. Even more importantly, I’d spent 20 years forming relationships, getting to know people who live and fish on the river, tribal members whose families have been here for thousands of years. The story of this river and of these communities is absent from Seattle history books.

When you learn about Seattle history, not only do you not learn about the [river] that made the city of Seattle possible, but you learn fallacies about our history. So by writing a history not just of the river, but a history of Seattle using the river as a lens, I’m hoping to help Seattle better understand itself.

What happened to this river and what happened to the people who lived on the river before, or have moved to this river since, have everything to do with one another. In addition to the 10,000 years of the Duwamish people being here, we’ve got seven generations of settler and immigrant history here. Starting with early European and American immigrants to the more recent Latino, East Asian and East African immigrants that are living here now, every generation changed the river and the river changed every generation.

Those relationships that you’ve formed, can you talk about how those informed your work?

When I first started working on the river, my primary lens was environmental. I was looking at pollution sources and how we enforce the Clean Water Act, but I was very aware that the people who were most being impacted were those who were the most exposed and most vulnerable. I saw people fishing in this river all the time.

Once the neighborhood, tribal and environmental communities in Seattle were able to come together and get a Superfund listing through [the Environmental Protection Agency], I began coordinating the efforts among those groups so that we would have an advisory role with EPA that represented the needs of businesspeople, residents and tribal members. The 25 years that I spent doing that was really about trying to make sure that all of those folks were starting to talk.

In the course of that, [I got] to know some of those stories myself, and how not knowing them led people not to value what’s here. This book would not exist without those folks sharing their stories and wanting those stories told.

You describe how Lake Washington was “cleaned up” by having sewage diverted to the Duwamish River. I’m curious how you see the issue of “If you don’t see it, it’s not there.” Do you see that as a form of environmental racism, as ignorance that turns malignant?

It’s blatant environmental racism. Does that mean that every single individual person of wealth living on Lake Washington is personally a racist? I’m hoping we’re getting past that conversation. There are institutionalized forms of racism that are not personal, that are systemic. It’s about the values that we hold as society overall.

We valued Lake Washington in part because it was a recreational playground for people with money. We valued the Duwamish also, but we valued it because it was a base for industrial development in our city, not because it was a recreational area, a tribal area, an area where immigrant families fish. We valued it for different reasons, and we treated it accordingly. And as a consequence, we treated those people accordingly, because they were not valued.

The fact that Native people were expelled as soon as we formed the city is absolutely essential to telling this story. People like James Rasmussen, who’s a Duwamish tribal member and served for a decade directing the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition — being able to understand how those actions impacted him and his family and their efforts to continue to be stewards of this river is a huge part of Seattle history.

Why is it so important to make fish in the Duwamish healthy to eat again?

So long as the fish remain contaminated, which many people think will continue long past finishing this cleanup, that is affecting people’s lives and health every day. It’s affecting their medical health, it’s affecting cultural health for folks who come from fishing traditions, be they Native or immigrant. Many immigrant families who fish this river come from generations-long fishing traditions in their home countries. That’s part of why they settled here.

Then, for folks like James Rasmussen or Ken Workman, members of the Duwamish Tribe, it also affects their spiritual health in really deep ways. I can say those words, but I can’t even begin to understand, because this is their family. This is what ties them through 10,000 years of life here. So whether you’re talking cancer-type health or intergenerational cultural health or deep-rooted spiritual health, if we can’t clean up the fish in this river, we’re in trouble. All of us.

That’s our biggest challenge right now. We can drag mud out of this river. We can try to stop ongoing sources of pollution, but the effort the way it’s defined right now is probably only going to get us halfway there.

What has brought you hope?

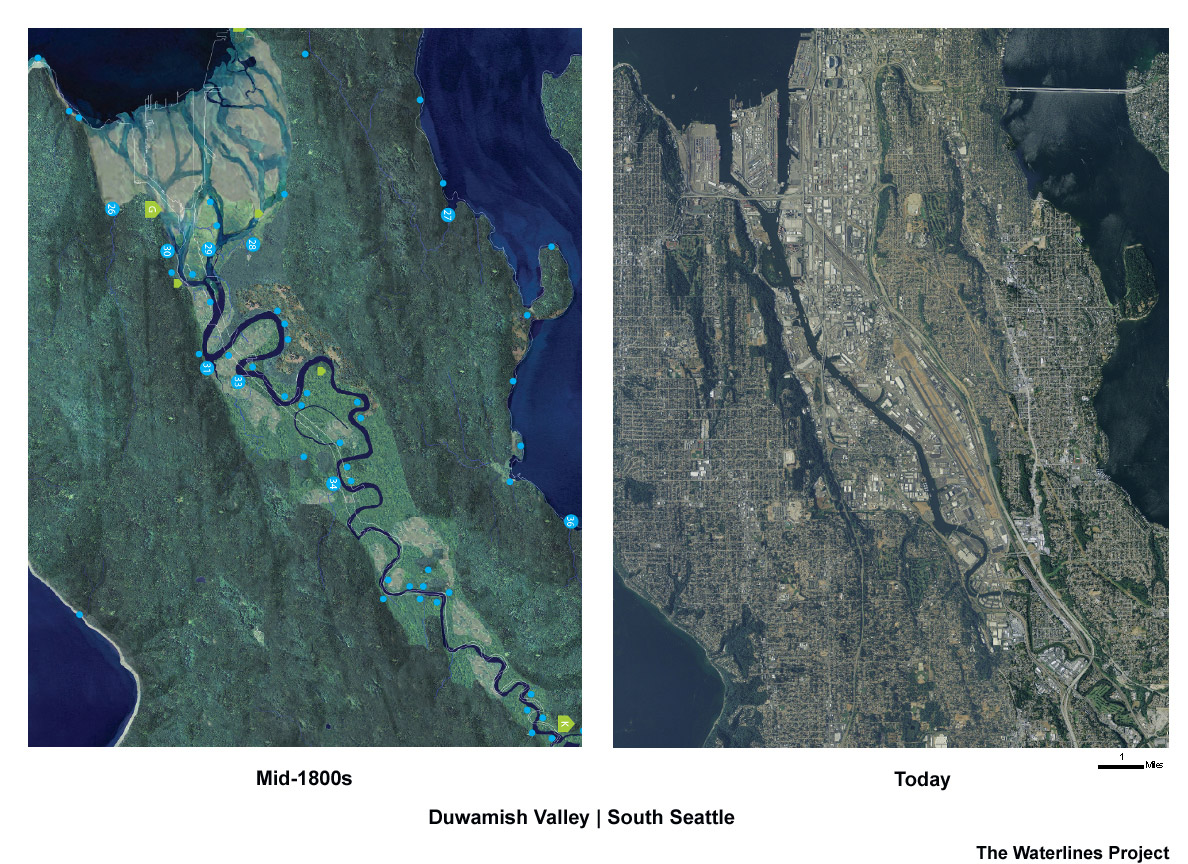

Industrial business owners are sitting down and talking with tribal members, recent immigrants who represent fishing communities, and the EPA. And everybody is hashing through the details of how we’re actually going to do this, where we wind up in a place where this river is for everyone. We went from 1850, where this was a “natural” river (albeit managed by the Native people who were here), to a wholly industrialized river in 1950. In the last 30 years, we’ve been trying to restore some balance. Nobody’s trying to take it back to the river of 1850, but nobody wants it to be the river of 1950, either.

The fact that people on all sides are sitting and talking together about the nuts and bolts of how to actually move forward, that’s hopeful.

What does the relationship between environmentalism and industry on this river look like right now?

We’re sitting on this lovely bend on the Duwamish River, the last remaining natural river bend. You can see the top of LaFarge Cement plant. That’s one instance where a local business has saved itself by becoming part of the cleanup industry. Demand for their goods was going down, they were losing labor, they had shut down an entire shift. Now they’ve been able to start hiring again. They are more economically sustainable, because they’re doing pretreatment of the contaminated waste coming out of this river, loading it onto rail lines after processing it at the plant and getting it out of the city and into safely engineered landfills in Eastern Washington and Oregon. They were on the decline, and they’ve been stabilized by becoming a part of the cleanup industry.

There’s so much work that needs to be done to clean up this river. There’s thousands and thousands of jobs, and millions and millions of dollars in that. So I think that’s going to be the next decade or two of the Duwamish industrial area — a large part of it is going to be cleanup business.

If we’re successful in what we’re trying to do here, and we remain committed, I think it can be a model. There are other models that we’ve learned from, and I hope we can return that by improving on them and being an inspiration and an example for other places. We’re far, far ahead of many states and their contaminated sites throughout the country. This is a pretty dark time. If we hadn’t gotten a final cleanup plan that’s legally binding when we did, I’m certain we would not be having the success that we’re having today.

How does the interplay of local, state and federal power matter to this particular place? How did citizens stand up to or demand action from those powers?

Power has everything to do with this. That’s part of why all these groups came together 20 years ago. Separate, they were absolutely powerless. That includes the Duwamish Tribe. They have no federal recognition, so they have no power in that sense. South Park Neighborhood Association: the city couldn’t have given a darn 20 years ago. Georgetown: everything that the rest of the city didn’t want was being located in Georgetown. Without that combined power, we would not see the cleanup that we’re seeing today.

If we had a different federal administration when this cleanup was approved, we would not be seeing this cleanup today. But if we had a different local political and business environment, it would also be different. Three of the largest polluters with liability and responsibility for cleaning up this river, are our local governments: city of Seattle, King County, and the Port of Seattle. Others, like the Boeing Company, are part of that, as well, but three of the largest four are [controlled by] local elected officials who are accountable to local people. We were able to leverage people power that community organizations had built over the years to turn it into city, county and port support, despite [their] having to pay for it.

I’m curious whether you’ve encountered the sense from local officials that things that happened a long time ago are not their responsibility. How do you combat the sense that this history — that maybe you didn’t take part in — that there’s still a responsibility to deal with it?

We’re back to the institutional racism issue. Seattle would not have been possible without tapping the human and natural resources of the Duwamish River. Now we’re this “world class” city with wealth that’s unheard of, even within the United States, and we have that because we built the city on the back of the Duwamish River.

We have an obligation to the river itself, and to the communities, Native and otherwise, that have paid the price for that success. There are people living, fishing and with cultural ties to the Duwamish River who are dying 13 years younger than people living in the wealthy enclaves that depended on the capital resources of this river. It’s time to turn that around.

Update: This story was updated at 12:39 p.m. on June 30, 2020, at the request of BJ Cummings, to reflect that those living in Seattle's wealthier neighborhoods can expect to live up to 13 years longer than those living near the Duwamish River, not 14 years.