“I’d like to address a rumor I’ve heard that officers assigned to the East Precinct have been told to remove their personal belongings in preparation for an abandonment of the building,” reads the Sunday, June 7 email obtained by Crosscut. “Let me state very strongly that this is not the case. It is the strong position of both Chief [Carmen] Best and myself that we will not abandon one of our facilities to those who are intent on damaging or destroying it.”

But by Tuesday, that’s exactly what happened.

Nearly two weeks later, not only has no one claimed responsibility for ordering officers to stay away, but it’s unclear whether there was an order at all. According to two police sources in the East Precinct, they never received any written command to not come to work on Capitol Hill. Instead, they were told by text or phone call from colleagues to head instead to the West Precinct on the north end of downtown Seattle — a sort of organic game of telephone.

“I'm not sure if someone said something to somebody or someone got a call from somebody. We're still trying to track down exactly how it got to be that people were actually leaving the facility,” Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best said in an interview this week. Best repeated that it was not her decision to leave the precinct, and that she wants officers to move back into the building.

“Whatever the cause was, ultimately officers did leave and with the intention of returning, and we weren't able to facilitate the return,” she said.

After the police exited, the street corners just outside have transformed into a 24-hour, “no cop,” protest zone — an extraordinary and controversial microcosm of a community that’s predicated on anti-racism, mutual aid and the rejection of police.

The zone, now known as the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, or CHOP, has drawn the eye of international media, as well as the president of the United States. Portland protesters have tried to create something similar. The area — a utopia for some, a hellscape for others — has come to represent the epicenter of the country’s cultural divides.

For some officers, however, it’s become a symbol of ineptitude in department and city leadership. Inside the West Precinct, where East Precinct employees have been temporarily housed, officers have printed off Mahaffey’s June 7 email and posted it on bulletin boards and outside the station in an act of protest, according to sources and photographs provided to Crosscut.

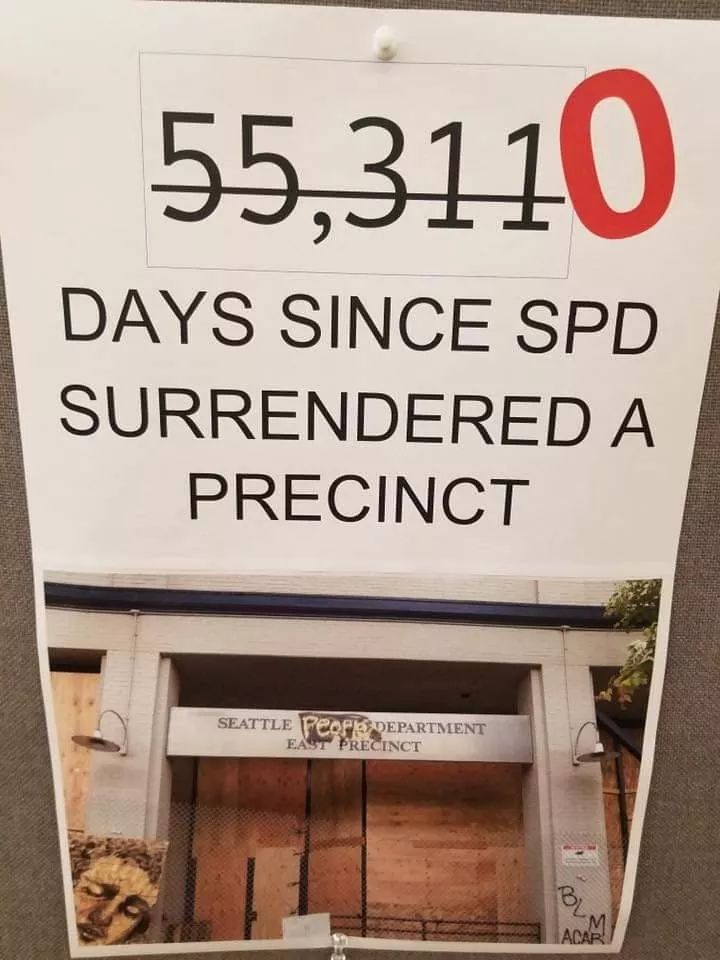

One employee posted a sign inside the West Precinct that reads “55,311 days since SPD surrendered a precinct.” The large figure is then crossed out and replaced with the number of days since officers left, a spin on the signs seen at construction sites marking the number of days since a serious accident.

Best said it had not been the department’s intention to mislead its officers. “I wanted the officers specifically to know that, especially after we had said that we had no intention of leaving the precinct, that we were telling the truth there,” she said.

Mayor Jenny Durkan, meanwhile, has downplayed the significance of the protest area. “People have a constitutional right to gather, to protest and to exercise their First Amendment rights,” Durkan said in an interview. “It's a fundamental right guaranteed to them by our Constitution and one of the most important rights we have.”

Asked about the officers usually stationed at the East Precinct, Durkan said the current moment — of COVID-19 and now the protests — means city employees must be flexible. “Flexibility in the workplace is something that we have become very adapted to,” she said. “And you know, in the short term, the need to kind of have a singular place to do business, I think, is outweighed by the need for the city right now to heal.”

The precinct’s desertion came shortly after Durkan ordered the barriers near the station removed. The barriers had become the scene of nightly clashes between protesters and police. “It was really important for us to break the cycle of violence on the Hill and to bring peace to Seattle for a period of time so that we could restore both trust and order and the ability just to have dialogue,” Durkan said.

Durkan also passed down an order for police personnel to secure sensitive technology and equipment, but not to leave, she said. Protesters noted moving trucks outside of the precinct, taking out boxes and other equipment.

With the barriers removed, property protection material — including fences and flame-retardant foam — was moved closer and closer to the precinct itself, until the building was essentially wrapped in chain link and boards.

It was then that word began spreading among officers to not come back to the precinct.

In the confusion of the police department’s exit from the building, equipment — both personal and professional — was left behind or not catalogued properly. Some of it has gone missing.

“As you can imagine during the chaotic departure from the East Precinct numerous equipment items have gone missing that officers are looking for,” Sgt. Joshua Ziemer said in a June 13 email to officers, also obtained by Crosscut. “A lot of the equipment was thrown into patrol and other department vehicles during the rush. I am asking officers to check the vehicles they are using and around the precinct they are working for items that may have been moved from the East Precinct.”

For officers who were not on duty at the time, most of their equipment — uniforms, shoes, ballistic belts — was left behind. The department authorized East Precinct employees to go to Kroesen’s in SoDo to buy new gear, including shoes and shirts, according to the two sources.

Best initially blamed “the city” for the decision to abandon the precinct. She also was forced to walk back comments about businesses being extorted by protesters within the zone. And there have been some semantic disagreements about law enforcement presence in the area.

“I will say that communication is always a challenge in any large organization,” Best said.

So far, no timeline has been provided for when — or if — SPD may try to return to the East Precinct. Durkan has shown she’s willing to be patient.

“Even in the history of Seattle, it is not uncommon for parts of the city to be closed for protests or events,” she said. “Occupy Seattle had the block behind my building and the courthouse for a very long time. I would bring them food…. So I think that the concept that people might want to have a place where they continuously voice their concerns and exercise their right to assemble is as honored a tradition as America has.”