Today, we hear the rumblings for the recall, resignation or impeachment of Durkan as she faces a unique set of problems and crises. But Durkan — the first Seattle-born elected occupant of the office and only the second woman to hold it — is not the only mayor who a fractious city has demanded leave. Usually the ouster occurs by way of the ballot box, though in our history two have been recalled and some have resigned, often because of the office’s high demands and low rewards. Few leave it beloved.

Those demands can be difficult. Durkan isn't the only mayor to try to guide the city through hard times. John Dore led in the Great Depression. He carried a gun, meeting families in his office and giving them money for food from his own pocket. He campaigned in a boxing ring. The pugnacious mayor was voted out for his efforts. He died in office shortly after losing reelection.

Bertha Knight Landes, who became the first woman mayor of a major American city nearly a century ago, came in with a metaphorical broom to sweep out corruption in 1926. She fired the police chief in an effort to reform the corrupt department — a chronic problem throughout Seattle’s history. She sought to run a cleaner town. She lasted two years before the voters changed their minds about having a housecleaner. Her successor, Frank Edwards? He wound up being recalled.

Wes Uhlman came into office in 1969 from the state Legislature, a bright young man of 34 who, Seattle magazine famously speculated, might grow up to be president of the United States. His City Hall inbox was overstuffed with a cow pie of problems, from freeway-blocking anti-war marches and a variety of occupations. He was confronted with a long legacy of racism challenged by Civil Rights advocates, and there were a number of radical bombings to contend with. There was also a growing controversy over school busing, and he was dealing with a then perennial issue: a police payoff system. The greatest challenge came from Uhlman’s Welcome Wagon gift: the Boeing Recession of 1970.

A little over a year ago, I interviewed Durkan in the midst of numerous challenges. The Alaskan Way Viaduct was coming down; Seattle was coming out of the traffic “squeeze.” But with the opening of the new waterfront tunnel going pretty smoothly, in contrast to its preceding delays and cost overruns, light rail progressing and the new waterfront aborning, she was upbeat: “You cannot fear the future,” she said. If we manage the changes and opportunities, she said, we could be on the brink of the city’s “golden years.”

How quaint this optimism, expressed exactly a year before the COVID-19 shutdown. Consider Durkan’s current crisis list: a major recession and perhaps a new Great Depression on the horizon; massive budget cuts ahead; a city council flexing its lefty muscles; a downtown beset by stay-at-home orders and vanished tourists, its economic engines staggered, including Nordstrom, Pike Place Market and the Washington State Convention Center; the coronavirus pandemic with its dangers and unknowns.

Massive and continuing Black Lives Matters protests are demanding an end to racism and asking for radical change. Yet the heavy-handed response to them has underscored exactly what they have been about: violent overreactions by the police, who, in Seattle, are already under federal scrutiny for a history of excessive use of force — scrutiny Durkan wanted lifted before George Floyd was killed.

The new demands to “defund” or “abolish” the police set the bar almost impossibly high for the mayor of a major city. So, too, fixing the existing system. Part of the fallout is a controversial “occupied” section of Capitol Hill and its police precinct. Accompanying it has been a war of words with Donald Trump, who has threatened to bring order to Seattle if Durkan can’t. The city’s national brand is swinging wildly. Are we about Amazon or anarchists?

Then there’s a crisis that in any other time would be on the front pages daily: The West Seattle Bridge is broken, a huge part of the city essentially cut off. Infrastructure issues are always a big deal in any mayor’s term, but a crumbling major link — especially one that provokes a strong sense of déjà vu — demands attention and a solution and usually carries a hefty price tag.

Has there been any other time in Seattle history when a mayor has had so many problems and challenges? Yes, but you have to go back to Ole Hanson, son of Norwegians who manned City Hall just over a century ago.

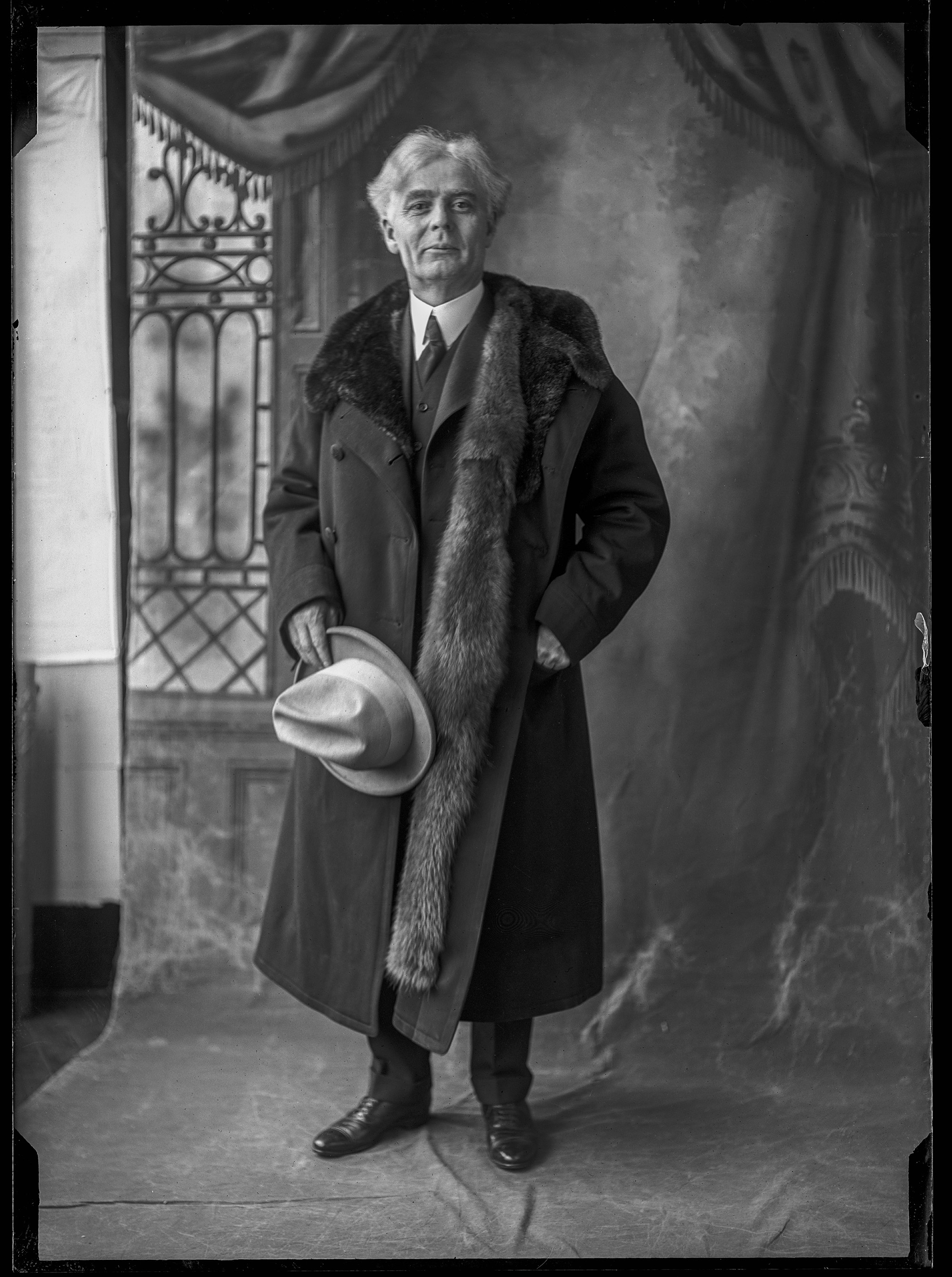

Hanson was not a newcomer to politics when he became mayor in 1918. He had been a real estate developer. On his first day as a newcomer to town, in 1902, he took his wagon to unsettled Beacon Hill and decided he would someday be mayor of the city that lay at his feet. He served in the Legislature and became a Bull Moose Progressive with a reputation for reform like his hero, Teddy Roosevelt. Hanson noted that Seattle’s mayors — whoever they were — ended up beholden to either labor, or the chamber of commerce.

It’s a dynamic we're familiar with 100 years on. Former Mayor Mike McGinn picked up Hanson’s memoir from a City Hall bookshelf, Americanism Versus Bolshevism, near the end of his tenure at City Hall in 2014. Most of the book is an anti-Industrial Workers of the World, anti-communist screed rooted in Hanson’s experience with radical labor in Seattle. Still, Hanson’s view of the power dynamics struck a chord with McGinn, an activist, for its clarity about how the mayor's office is viewed by the powers that be. “Cities exist for a reason, usually a commercial one,” McGinn says now. To a degree, mayors exist to “facilitate the transfer of funds” to the business community. “Look at Seattle mayor; no matter where they come in, they almost always go out allies to the chamber.”

As Hanson tells it, he decided to run as a pragmatic, honest independent, a reform candidate to replace the corrupt, shape-shifting politics of Hiram Gill, who had been recalled in 1911, but reelected later. Gill was a chameleon and a crook. Hanson insisted he would not be a pet of the powers, either labor or commerce or other corrupt systems in place. He wrote: “Few ever ask an independent free man to seek office! Usually those who ask you to run want something in return an honest man cannot grant!”

Hanson won. He knew at the start the job would be a challenge. The U.S. was fighting World War I and Seattle was in the thick of moving men and materiel and mobilizing industry for the war effort. It was teeming with workers, soldiers and sailors, prices were out of control, venereal disease was so rampant that, for a time, the Army made Seattle off limits for the troops. Meeting the demands of the war effort was a fulltime job. Hanson wrote later he wanted to be a “war mayor.”

If that wasn’t enough, the Spanish Flu pandemic hit in October 1918, and Hanson had to take the unprecedented step of shutting down the city and forcing people to wear masks. The public hated it, but it worked pretty well. Still, close to 2,000 Seattleites died from the virus, including Hanson’s predecessor, Hiram Gill. The mayor’s hard-headed Scandinavian pragmatism seemed to pay off.

But a new crisis loomed just as the flu faded, and it defined Hanson and his legacy: the Seattle General Strike of 1919.

If you think CHOP is giving Seattle a radical reputation, the General Strike saw America go nuts over the town portrayed as the new Moscow, the beachhead of Bolshevism on American soil. Hanson went nuts, too. The strike was a peaceful shutdown of the city for a few days, supported by some 60,000 union members, only a tiny fraction of whom were radical IWW members. Hanson, a silver-haired, flamboyant real estate promoter given to speechifying, turned it into a Red menace threat, a conspiracy of immigrants and communists to destroy America and democracy. True, there were radicals who sought that, but they were a passionate minority. They were loud and seen as traitors and outliers. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer called the strike a “delirium-born rebellion.”

If so, Hanson’s over-the-top response was a delirium of its own. He wrote that his job came from managing the business of a burgeoning city to be the de facto “glorified police chief.” He issued a proclamation: “Anarchists in this community shall not rule its affairs. All persons violating the laws will be dealt with summarily.” He mobilized the police, called in the Army from Camp Lewis and armed thousands of civilians.

The strikers were peaceful, most not radical. They wanted the pay increases that were promised them when the war ended. Hanson had supported nonradical labor. He had pushed through an increase in daily minimum wage for workers, from $4 a day to $4.50. Still, the mayor began painting all the strikers Red with a broad brush. He blamed Gill for not suppressing “sedition and treason” in the city earlier. He railed against the pro-labor newspaper, the Union Record, for fanning the city into a “state of unrest, of hatred, of lies and suspicion.” Labor’s response: They referred to Hanson as head of the “Ole-garchy,” and for his anti-Red proselytizing he earned the nickname "Holy Ole."

Before the strike, Hanson’s police clashed with unionists outside the Labor Temple, brawling with workers who celebrated a red flag on a passing truck. It was, remembered Hanson, “the first open battle between the forces of law and order and the IWW in Seattle.” He crowed, “Given 200 Seattle blue coats and 1,000 Reds — the Reds run!”

Hanson whipped his hard stand against the strike into an existential war for the survival of the United States. To many in business and the media, the end of the peaceful strike after less than a week did not mark the success of the protest but the triumph of Hanson’s tough talk and bold actions. The story of Seattle's mayor defeating the Red enemy went viral: Hanson became a national figure featured on front pages of newspapers all over the country, a secular evangelist standing against the Red Menace.

In Seattle, his reputation was different. Seattle rarely exalts a mayor and Hanson was no exception. He had helped defuse the IWW, but organized labor grew stronger and strikes, and violence, continued. The city’s police department remained corrupt, a condition exacerbated by the bootlegging temptations of Prohibition.

After a little more than a year in office, Hanson quit and left Seattle, perhaps encouraged by an anarchist bomb sent to his office that failed to explode. The city’s war aftermath, political and labor tensions, demands of the business community and pandemic fallout were going to be someone else’s problem.

He moved to California, went back into real estate and wrote an exclamation point-filled memoir of his own heroics. He hoped to run for president in 1920, but the effort fizzled. Still, his term in Seattle was action-packed, if brief.

Rather than breaking the mold of Seattle mayors, some saw Hanson as just another in a long line of disappointing leaders. In the book Revolution in Seattle, author Harvey O'Conner quotes an unidentified Seattle police official of Hanson’s time who wrote this assessment: “Hanson was the type of man who so frequently appears in Seattle chronicles as a mayor. He was energetic and picturesque, made rabble rousing speeches, but did not say anything and accomplished even less.”

Hanson saw Seattle as a “great business institution” that he had hoped to manage, to steer from its frontier period into a modern era. “The position of mayor was a trying one,” he reflected in his memoir. He learned very quickly that cities were much more complicated “businesses” than they appear. Even knowing that the job is complicated doesn’t always help when the issues rise like a flash flood. Few periods in Seattle’s city’s history have been more complicated and more challenging than during Hanson’s term. He leveraged the job into brief national celebrity, but after a year, he’d had enough. Seattle had, too.

History suggests there are cautions for Durkan. There are so many ways a city can go wrong, and only so much a mayor can do about it. Seattle's "golden years" might be further down the road because of current challenges, but Durkan's words from last year should resonate for all of us: "You cannot fear the future." It applies to her, as well as the rest of us.