In the midst of it all, people sought to take advantage of and profit from the social chaos.

Wartime prices for many goods were high and profiteering was a national problem. The U.S. government tried to crack down by implementing an “excess profits tax” on war-related windfalls. Regulators were on the lookout for bad actors looking to profit from wartime. They were concerned with those who created economic hardship for innocent people by inflating prices and otherwise violated the sense of patriotic duty whipped up for the war effort.

Fighting the landlord profiteers

Rental housing demand triggered profiteering in Seattle. As new workers — men and women — flooded into the city, mainly to work in the shipyards, housing was in short supply. Before the pandemic hit here in the fall of 1918, labor groups and angry renters — particularly apartment renters — were already protesting what they called “rent hogs,” landlords and lease owners who were gouging renters.

For more on the Pacific Northwest's last pandemic experience, see Crosscut's entire series on the 1918 flu outbreak.

- Before coronavirus: How Seattle handled the Spanish flu

- Premature optimism in a pandemic can be deadly

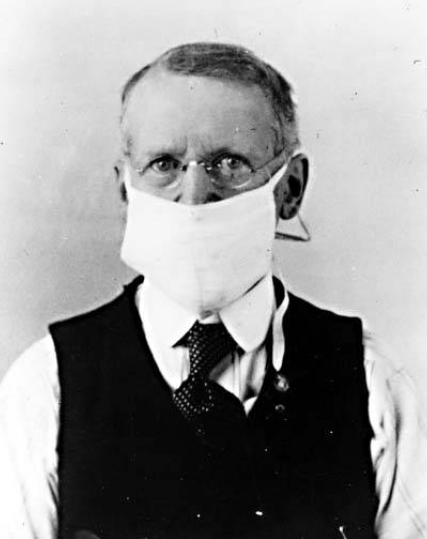

- Meet the Anthony Fauci of 1918 Washington

- Seattle struggled with suicide in late stages of the 1918 flu

- Podcast: What the 1918 flu can tell us about life after COVID-19

A citizens group called the Anti-Rent Profiteering League was formed to demand that the city and state adopt rules to stop landlords from taking advantage of tenants. Citizen activists, including Frank Walker of the Metal Trades Council and high school teacher Anna Walker, were part of the group. It threatened to prepare a blacklist of bad landlords and send it to Congress and federal officials scouting for wartime profiteers, such as the U.S. Shipping Board. This was the federal entity charged with making sure the country met its merchant, civilian and naval reserve maritime needs. Landlord profiteering was inhibiting the maritime labor force.

There were other landlord problems. Many would not rent to families with children. A Seattle housing committee charged with helping to find accommodations for incoming workers reported that 90% of rental listings barred kids. The Seattle Chamber of Commerce and other business groups argued that the problem was too little housing and an issue of the market, but the pattern of rent increases was frequently tied to speculation in leases and properties. Every time a building or lease was sold, speculators could raise rents. The Seattle Star reported that one building on First Hill had changed hands nine times in three years, and almost every time the change in ownership triggered rent hikes. Two- and three-bedroom apartments went from $15 per month to $50. In today’s dollars, that would be an equivalent leap of $263 per month to over $900.

In October 1918, in the midst of the influenza shutdown of public schools, theaters and all gatherings, even the pro-business Seattle Times roused itself to outrage over lease speculation. “The ‘lease speculator,’ whether he operates on a large or a small scale, is not needed in Seattle. Rout him out!” the paper editorialized.

Mossback's Northwest: Tragedy and terror in 1919 Centralia

The problem became acute that fall as the pandemic neared its peak. Added to the list of housing problems were alleged heating fuel profiteering and complaints that the city’s health department was not keeping its own housing properties in sanitary conditions, nor was it properly inspecting others properties. Unhoused families, high rents, high heating costs and lack of sanitation: None of these would help stem a pandemic, let alone help beat Germany.

Complaints to the federal government resulted in a September visit by a representative of the Labor Department. Investigations into landlords, based on tenants’ complaints, were discussed — though many individual renters were reluctant to come forward. In addition, a new local housing board comprising labor, the chamber, the YMCA and others was planned to help coordinate housing and handle profiteering complaints.

The city council took up changes to the law that the Anti-Rent Profiteering League proposed to stop rent-hogging. Raucous public meetings with angry citizens and angry landlords ensued; Seattle nice was not in evidence. But under pressure, the council bent to the property owners by insisting on studies and delays. A year after the Armistice and with the pandemic largely faded, many of the ideas were tabled for further “study” by the council.

Read more: My grandmother nearly died during the Seattle outbreak of the 1918 flu

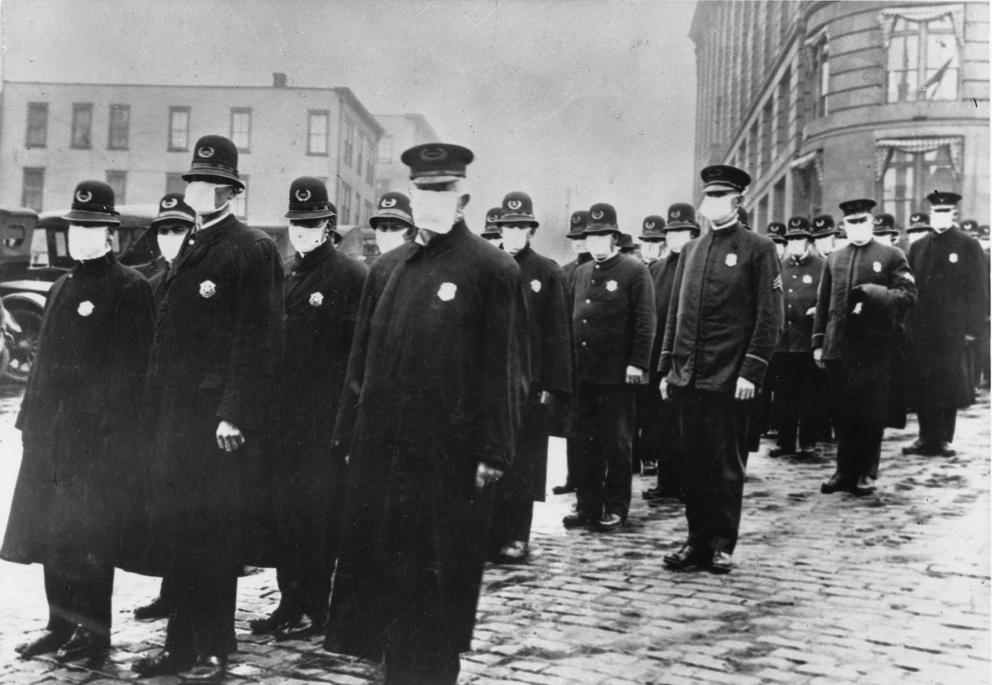

There were other examples of profiteering directly tied to the pandemic. For example, during the Seattle shutdown in October 1918, Seattle Mayor Ole Hanson raged against retailers who were selling cloth masks that the city distributed to drugstores for more than the 5 cents they were supposed to charge. “They are trying to capitalize on the city’s misfortunes,” Hanson railed. “They ought to be ashamed of themselves.” Masks were being sold for up to 25 cents. Druggists denied the charges.

Exploiting dead sailors and their families

Perhaps the city’s biggest and most publicized wartime profiteering case during the pandemic period was the indictment of Gilbert M. “Bert” Butterworth, head of the prestigious Butterworth Mortuary. Then located on Capitol Hill, the family funeral home had been serving the city since the 1890s.

In December 1918, at the height of the pandemic, a federal grand jury indicted Butterworth on 46 charges of violating the terms of a contract he had with the U.S. Navy to provide inexpensive funerals for cadets at the naval training facility on Lake Washington. A number of Navy cadets who died from the Spanish flu there were among the first known victims of the pandemic in Seattle. Butterworth, it was charged, had contracted to provide $100 funerals for them and to bury them in hermetically sealed, zinc-lined coffins. He didn’t, and was accused of defrauding the government.

Prosecutors said Butterworth took advantage of the Navy victims’ families by supplying cheap unlined wooden coffins instead of the more expensive ones specified in the Navy contract. The funeral home also sent telegrams to encourage grieving families to pay for more extravagant funerals without letting them know that the government had already provided for a basic funeral. Butterworth also allegedly offered families hermetically sealed coffins at a much higher price.

The trial was a sensation, involving as it did a prominent member of the Seattle establishment, Butterworth, and the ghoulish accusation that he was preying on grieving families. Large crowds packed the galleries, including military witnesses, defrauded parents, school children and members of the city’s elite, including the police chief.

Butterworth hired a powerhouse legal team of four lawyers to fight the charges. A first trial in March resulted in a hung jury and many charges were dismissed. At a trial the following November on two remaining charges, the jury acquitted the undertaker.

Butterworth and his defense team claimed misunderstandings, clerical errors by staff and a wartime shortage of zinc. Reading through the newspaper accounts, it seems clear that his legal team was able to pick apart the paper trail of fraud and distance Butterworth himself from the allegations.

The whiskey cure and Prohibition

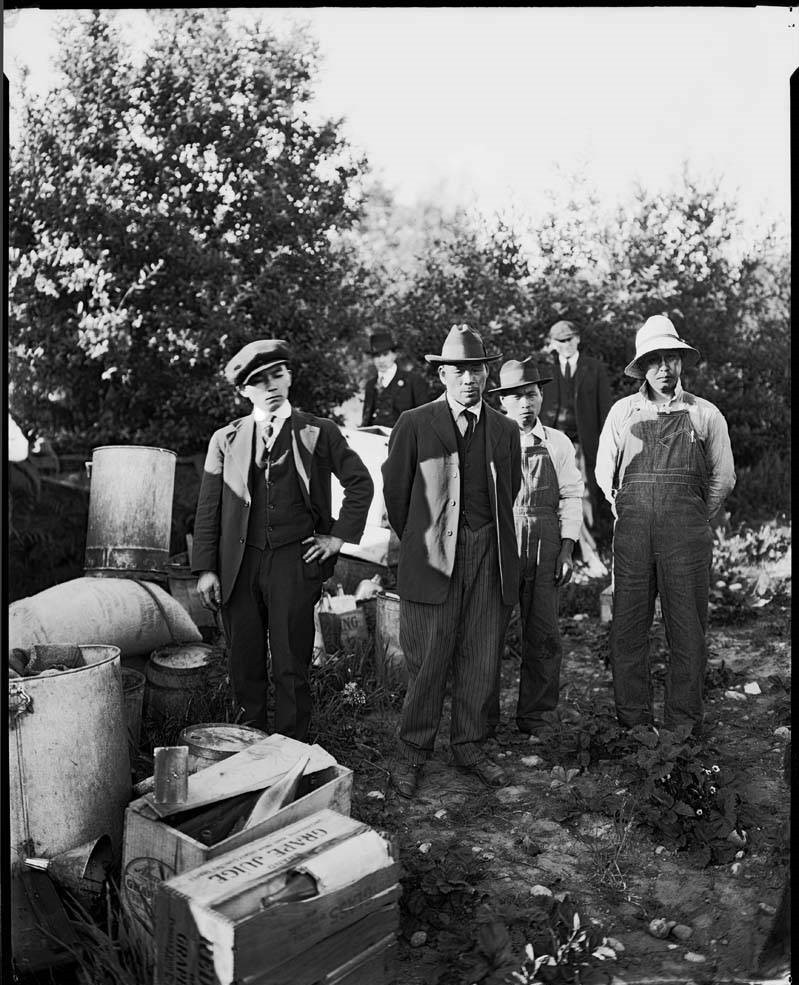

Prohibition and the pandemic meant that Washington’s anti-liquor laws were strict, and got stricter. The newspapers were filled with accounts of smuggled and stolen booze — shipments from Montana smuggled in by train, cargo for the Pacific stolen off Elliott Bay docks, secret stills busted for making everything from moonshine to sake. One ice cream parlor was shut down when the owner was caught serving hard cider instead soda pop.

At the beginning of the pandemic, drugstores could still sell liquor to customers with a doctor’s prescription — whiskey was considered medicinal for many ailments, including Spanish flu. But that practice was made illegal in November 1918, and druggists had their supplies of boozes confiscated. The sheriff donated much of the former drugstore supplies to Seattle-area hospitals to fight influenza, but one wonders if it was more for the relief of overworked medical staffs.

In a further crackdown that month, U.S. Attorney R.C. Saunders issued bench warrants for 14 proprietors of local drugstores, including Bartell and G.O Guy, for selling “remedies” and tonics with high alcohol content (from 18% to 90%) to get around prohibition. The object was to keep them out of the hands of soldiers and sailors — to make Seattle “bone dry” within 5 miles in every direction of a military post. A hair tonic from Montana was banned because it was over 40% alcohol. In Bremerton, a man went to jail for selling a common tonic called Beef Iron and Wine to a sailor because it was about 20% alcohol. Think of it as a kind of boozy Red Bull.

Law enforcement often played both sides during prohibition. The so-called Seattle police “Dry Squad” cracked down on liquor sellers, but some secretly were in the pocket of bootleggers. During the pandemic, a large supply of confiscated booze went missing from police custody. This might be a clue to where some of it went: Police Chief J.F. Warren suspended for 10 days a patrolman named H.R. Flattum for being drunk on the job one night in December 1918. He was found to be in a “befuddled condition.” Flattum’s defense: he had poured alcohol into a cup of coffee “to ward off the influenza.” A little over a year later, Flattum was fired for running amok, waving his gun and terrifying guests in the Hotel Federal, at Third Avenue and Pine Street. One witness told police he was “crazy drunk.”

Despite the hopes of some pandemic victims suffering from civic dryness, doctors treating the Spanish flu determined that whiskey was of no help against the virus, much as some patients might have wished otherwise. If nothing else, it might have eased the stress caused by war, pandemic and profiteers.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated incorrectly that rents in one First Hill apartment building jumped from $90 to $900 in today's dollars. The correct figure is a jump from $263 to $900.