Seattle in 1942 saw itself on the front lines of the Pacific campaign. The city was growing with a new, diverse wartime workforce, even as it expelled its Japanese and Japanese American residents. Troops and troopships sailed in and out. Because the population boom could not be planned for in advance, an acute housing shortage took hold. The declaration of war after Pearl Harbor, at the end of 1941, meant rapid expansion, not least for Boeing, which was supplying B-17s to bomb the Nazis. The factories and shipyards were filled with Rosie the Riveters helping build those ships and planes for the war effort.

This is the second in a two-part series on the origins of the Seattle Freeze. You can read the first part here.

Into this mix came Martin and Helen Miller and their young son, one of many families who came to town for wartime employment. Martin Miller was a newspaper editor making a modest salary, and he and his wife were looking for a place to live. They came from Idaho, and were stunned by Seattle’s prices. Even for a working class white family, trying to find a place to live in wartime Seattle was a battle in and of itself.

Their search for a home and reception by locals were infuriating. After many long months trying to settle in Seattle, Helen Miller, writing under the name of Helen Markley Miller, decided to vent in an article published in The Seattle Times. She gave full throat to her complaints and what she thought of the residents. The Times in turn gave her complaints front-page treatment.

“Seattle as a word may have a musical sound, a lilt of its own to all you elder residents, but to me it is an Indian word meaning ‘pfui,’ ” she began, using the German spelling for “phooey,” an expression of contempt. What followed was the saga of a family of modest means moving to the city, only to be thwarted at every turn in their hunt for a home.

“We topped the mountains and drove down into your lovely city over charming Lake Washington. We saw and loved Seattle’s greenery and water, the blue Sound with jagged, misty mountains pushing up the friendly sky. We liked the skyline, so bold and strong and massively builded; we liked the shops and the crowds and the streets. We liked the whole damned town, that first afternoon.”

First impressions with Seattle are often good. Miller’s optimism echoes down the decades — but Seattle’s irrepressible natural urban charm soon reveals a tougher reality. This beautiful city often promises more than it often delivers.

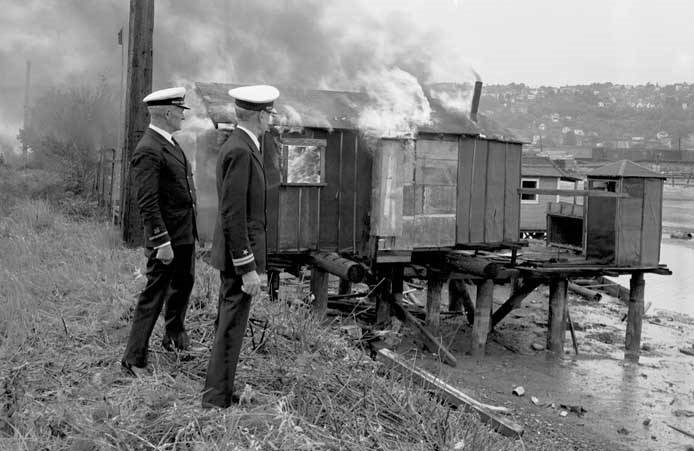

The Millers were frustrated trying to find even a temporary perch. Suburban car camps were full, and motels, if they weren’t full, were too expensive for an extended stay. Available places were often dirty and unsanitary. Helen was furious that renting a home, if one could be found, would cost $125 per month rather than the $45 one would pay in Boise. Real estate agents warned that no such home rentals were available anyway, and neither could anyone find affordable housing to buy. The only options were overpriced, poorly built “little boxes,” as Mrs. Miller referred to them. “I don’t think I’ll estimate how long they’ll stand on their pretty little fundaments,” she wrote, shocked that these slapdash abodes had no basements. Well-paid defense workers might afford them, she guessed, but not ordinary folks like the Millers.

Which was part of the frustration: “How I’d like to take one of you smug burghers, sitting at home reading this, in your smug home, over Via Dolorosa that a newcomer travels to your exhilarating city.” Housing, she complained, is hoarded by the locals for friends and relatives, or friends of friends, and “a place never stands vacant more than ten seconds unless it is infected with bubonic plague.”

To Helen Markley Miller, the result of the lack of affordable housing, and the closed clubbiness of Seattle old-timers, created “a class of persons which, through no fault of anybody’s, has lost a lot of purchasing power.” After being outbid for homes, Miller saw in the future a city of “world beaters” who have risen with the real estate values and left everyone else behind, unless it fell like some modern Jericho.

The Millers didn’t stay long. But before they left, they heard from the “smug burghers” of their momentarily adopted city. Letters about Helen Markley Miller’s piece filled many column inches of Times editorial space over the next few weeks.

F.A. Fenton of Seattle attacked Miller’s attitude and foresight and gave her a quick, defensive Seattle forearm:

“We, the smug burghers, have taken a good deal from many newcomers in the shape of unjustified criticism, overcrowding, and downright rudeness,” she wrote. “We realize that the war has brought about this condition, and hope to make the best of it as gracefully as possible. But to see a woman who makes a pretension of intelligence and education … criticize matters that no one can control and in such a flippant, thoughtless manner leads one to wish that so much perception might have been augmented just enough to decide Mrs. Miller to stay in her comfortable Northern Idaho until she knew the score a trifle better instead of coming here to further congest conditions.”

A resident who signed herself “A New (but permanent) Seattleite” supported some of Miller’s views from a perspective that outlines the nature of what some call the freeze:

“ ‘Smug burghers’ — a fervent Amen sister, from me! At least I think they are — so far in fourteen months I have met none of them socially. … After nearly dying of sheer loneliness for months, I found a solution of a sort for my own problems. Soon after it was organized I listed my name with the volunteer committee on the War Commission, and in due course of time I’ve been put to work. Gradually, work is making me feel a part of Seattle. It hasn’t given me friends among real Seattleites. … A lot of us came here to make a permanent home and we will remain, in spirt of your smug unfriendly hints for us to move on. We will rear our children here into ‘real Seattleites,’ but I sincerely hope not ‘Smug Burghers.’ ”

Another reader had her own complaints. Mrs. John Earls of Bryn Mawr said the newcomers had only themselves to blame:

“You new arrivals fall into two classes: Those who are here for the duration and a few who are here for keeps,” she wrote. “But you fall into one class when you get behind the wheel. Such driving — I must hold my tongue. Well, anyway, we were a nice peaceful town once and who has changed it? You’se guys.

A number of letter writers agreed that the housing shortage was a pain. At least one sought some kind of conciliation between the old-timers and the newcomers. Edward Colcock wrote that neither of the opposing views got to the real point or its solution:

“Underlying both sides of the controversy is a lack of Christian tolerance. The resident has been rudely and sometimes roughly shoved around by the vigorous entrance of the newcomer. Such a ‘shoving around’ should shake us loose from some of our own preconceived ideas and be good for both the city and those of us who have been long time Seattleites. … We should be grateful for this influx and make earnest effort to adjust ourselves to the inconvenience of this lusty growth.”

The Millers did not last long. They moved back to Boise, where Martin Miller became managing editor of the Idaho Evening Statesman for a brief spell before dying of a heart attack at age 44, in May 1944. Helen became the sole support of the family and used her writing skills to forge a career as a teacher and author of young adult historical fact and fiction. She wrote more than 20 books for major publishers, many of them about the West and frontier life, often featuring plucky young women and girls.

In 1961, she returned to Seattle for the first time since her unhappy wartime experience. The Seattle Times ran a short item about her coming back to speak at the Pacific Northwest Writers Conference and noted her writing for The Times, in 1942, about the housing shortage. “Mrs. Miller is one of those rare persons, a fulltime author, who depends upon the product of her typewriter for her income,” the paper reported. It mentioned her wartime article and noted only that Miller had found Seattle greatly changed. She died in 1984.

Seattle was fascinated, then as now, with seeing itself in the mirror of national adulation and newcomer critiques. A young city, Seattle tends to want to check its reflection frequently. Helen Markley Miller’s view reflected outrage that people like her and her husband couldn’t find a perch in such a promising city. She recognized, of course, that the circumstances were unusual, but her disillusionment was palpable, and it made good copy. She is certainly not the last newcomer to Seattle who decided to slam the door on the way out and rattle the city’s self-image.

By the 1940s, some families had resided in Seattle for nearly a century and considered themselves entitled to the comfort of having been early and constant. The 1920s and ’30s, despite the problems of redlining, Japanese incarceration and chronic poverty in South Seattle’s sprawling Hooverville, the city’s white middle class—the “smug burghers”—had solidified itself and held on to their mostly modest homes in leafy neighborhoods, where even bungalows could have million-dollar views. The beneficiaries of change had spawned a resistance to more change.

When Seattle’s population declined in the 1960s and ’70s, the push between newcomers and longtime residents went dormant, and housing became more affordable. But in times of growth and boom, from World War II to Amazon, the old debates over housing, affordability, traffic and neighborliness are animated anew.

The Seattle Freeze appears to be a cultural permafrost that is always right under our feet.