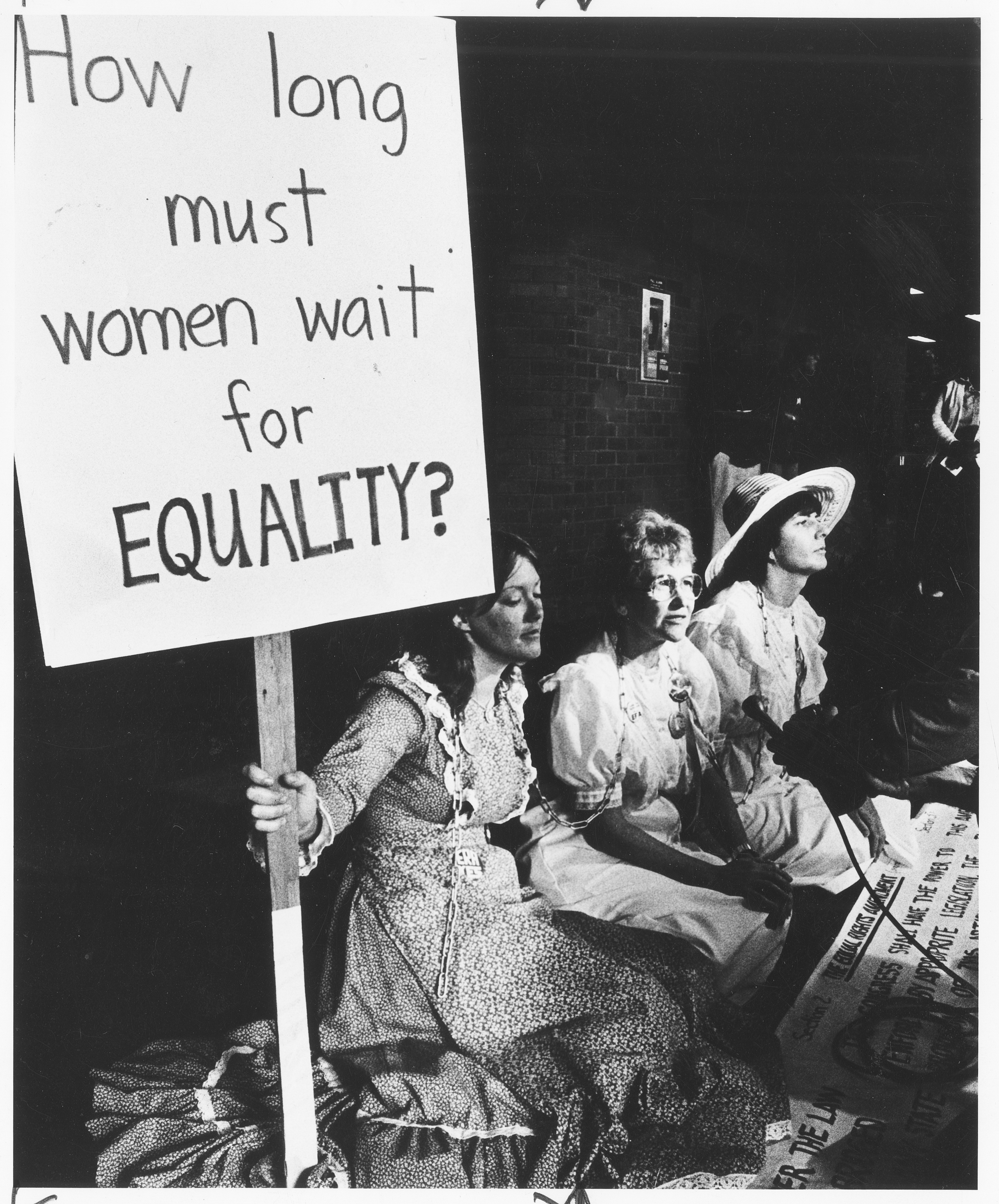

Now, as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which delivered that eventual victory, it’s an ideal time to reflect on the events in Washington state that helped get us there. The lessons here still hold true: Lasting political change can’t be done on the cheap. It requires broad, clever organizing to transform hearts and minds. And maybe some cherry pies and picnic lunches.

The unsung heroes of this story are two women who didn’t live to see American women secure the vote. Sisters Mary Olney Brown and Emily Olney French came by wagon from Iowa to the Washington Territory in 1852 and immediately began to cause trouble. They were abolitionists who wanted more than the abolition of slavery. They had the audacity to think that both the formerly enslaved and women should be able to vote.

When the Civil War ended in 1861, feminists had high hopes for liberation of both African Americans and women. Women had been stalwarts of the abolition movement. During the Civil War, the Woman’s National Loyal League, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, gathered 400,000 signatures on a petition to Congress to abolish slavery. It was at that point the largest petition drive in the nation’s history and significantly boosted efforts to pass the 13th Amendment, which ended slavery. Although these efforts didn’t translate into power for women, their experiences of sexism within the abolition movement transformed many of them into feminists.

Despite the leadership of women in the abolition movement, the 15th Amendment, granting the formerly enslaved the right to vote, did not mention women, and the 14th Amendment, granting equal protection under the law, wrote gender discrimination into the Constitution by providing for punishment of any states that denied their male citizens the right to vote.

Feminists were bitterly disappointed, but they did not give up. They reasoned that the 14th Amendment nevertheless entitled women to vote. Women were citizens, voting was a right of citizenship, and therefore women, like their male counterparts, were entitled to the franchise. Around the country in the late 1860s and early 1870s, feminists set about testing the theory. Anthony in New York and Sojourner Truth in Michigan attempted to cast ballots.

In Washington, Mary and Emily Olney did the same. As detailed in Shanna Stevenson’s book Women’s Votes, Women’s Voices: The Campaign for Equal Rights in Washington, Mary Olney went with her daughter to the White River polls in 1869 and gave an articulate, well-reasoned speech to the registrar, citing the recent constitutional amendments. The registrar was unmoved. The next year, in Grand Mound, near Centralia, Emily Olney organized a group of seven women to attempt to vote. But instead of making their assault on the polls with reason, these women decided the way to the ballot was through the stomach. The day of the election, they served the election judges a delicious picnic, discussing the question of women’s right to vote as they ate. Only after the judges were full and contented did the women try to vote. The judges accepted their ballots, and these women became the first ever to vote in a territory-wide election. Hearing that these women had succeeded, eight other women cast ballots in nearby Black River the same day.

The backlash was swift. The territorial Legislature responded by passing a law in 1871 explicitly denying women the vote. Nationally, the response was even more disastrous. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1874 that women might be citizens, but voting was not a right of citizenship and women had no right to vote.

But the Olney sisters were not deterred.

In 1883, after intense lobbying spearheaded by Mary Olney, including a statewide petition drive, the Washington Legislature voted to give women full voting rights, which included the right to serve on juries. Women soon turned out to vote in greater proportion than men. In both Seattle and Olympia in 1884, women voters gave the boot to corrupt city administrations, and they helped pass restrictions on alcohol sales and gambling.

Mary Olney died in 1886, not knowing her victory would not hold. Women voted for only four short years.

In 1887, Tacoma gambler Jefferson Harland, who had been convicted of swindling by a jury that included women, appealed, claiming women had no right to serve on juries or, for that matter, to vote. It seems likely that the case was fomented by liquor and gambling interests. In any case, the fix was in: The case was argued on a Monday afternoon, and the territorial Supreme Court issued a 15,000-word decision Thursday morning, overturning the entire suffrage law. The court based the decision on a technicality (that the suffrage law’s title was improper), but waxed eloquent on the proper sphere of women, in the home and out of civic life, not voting and not serving on juries. “The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life,” the court approvingly quoted from a U.S. Supreme Court decision.

Women indelicately protested, organizing petitions and letter-writing drives and lobbying. In 1888, the Washington Legislature again passed women’s suffrage. This time, seeking to placate opposition, the Legislature excluded women from jury service. The concession didn’t buy peace. Two months after the governor signed the bill, a Spokane woman filed suit because an election judge had rejected her ballot. The whole thing again reeked of a setup: The woman was the wife of a saloon owner, who apparently put her up to the task, and the election judge’s day job was as the saloon owner’s liquor supplier. The territorial Supreme Court again invalidated the women’s suffrage law.

This theft of the ballot would be harder to undo, because voters were about to select delegates to draft the new state constitution. The all-male voters selected all-male delegates. The male delegates in turn decided that only men should be entitled to vote under the new state constitution. From then on, regaining women’s suffrage would become even more difficult, requiring a constitutional amendment that could be enacted only by approval of two-thirds of the Legislature and a majority of the state’s voters.

Yet, in 1897, suffragists led by veteran activist Laura Hill Peters managed to wrangle the votes to push just such a bill through the Legislature on a two-thirds vote. As it was being handed to the governor for signature, a senator noticed that the bill had been mysteriously replaced with a dummy document — anti-suffragists had apparently stolen the bill. Peters tracked down the real bill and handed it to the governor, who signed it and sent it on to the voters — who rejected it, 30,540 to 20,658.

This was one in a string of suffrage losses around the country; in the late 1800s, men in 14 states considered and rejected women’s suffrage. After 50 years of demanding the vote, suffragists had only four lightly populated states — Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Idaho — to show for it.

So it was entirely against the odds when, in 1906, feminists began a campaign for the vote in Washington. Organizer Emma Smith DeVoe came from Oregon to lead the campaign, with support from the national suffrage movement. May Arkwright Hutton, a former cook in the Idaho mines and labor activist who got rich from investing in a mine, led the fight for the vote in Eastern Washington.

Although Emily Olney had died in 1897, the campaign finally took to heart her lessons. DeVoe drafted a suffrage bill, got a legislator to introduce it and corralled the votes to pass it. Realizing that the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was to be held in Seattle in 1909, she invited the National American Women’s Suffrage Association to hold its annual convention in Seattle at the same time, sponsoring a Women’s Suffrage Day and a “Women’s Building” at the convention, complete with child care. Kites and balloons emblazoned with “Votes for Women” hovered over the Seattle exposition site.

One feminist led a group from the exposition in a climb of Mount Rainier, planting a “Votes for Women” banner on the peak. Suffragists started a newspaper to spread the word, including a poster in each issue, as well as a recipe for poster paste. Taking a page right out of Emily Olney’s playbook, Hutton served 80 of her famous cherry pies at a Civil War veteran’s encampment before securing the men’s promises to vote for suffrage.

The suffragists also created a cookbook to raise money and to “make us friends among the men,” as DeVoe put it. It provided recipes for meat, pastry and vegetables, but also sections on housewifery, beauty secrets and mountaineering (with camp recipes, instructions on starting a fire and what to pack, including such essentials as rose water). The book was peppered with pithy quotations about women’s rights. The section titled “Pickles,” for instance, begins with a quote from Susan B. Anthony: “Failure is impossible.

The book assured men who worried that if women got the vote they might not put dinner on the table, “Give us the vote and we will cook the better for a wide outlook.” Organizers used the cookbook as a disarming way to start conversations with voters, going door to door to sell the cookbook — and using these visits as part of a plan to contact each voter in each precinct in the state. Suffragists laboriously catalogued individual voters by name, national origin, occupation and address — without the aid of software.

On Nov. 8, 1910, the question of whether to amend the state constitution to grant women the vote went to the male voters of the state. By a wide margin in every county, they voted yes. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer announced, “Women of the State Get the Ballot by Gift of Men.” It was true in a sense. Yet men had changed their minds because the suffrage organizers made them do it.

The Washington victory broke the suffrage dam nationwide. California passed women’s suffrage in 1911, Oregon, Alaska, Arizona and Kansas in 1912, and Montana and Nevada in 1913. To get the vote nationwide, women would have to make another great leap in organizing, but eventually, women won the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Washington state ratified it on March 22, 1920, and it became law in August 1920.

Unfortunately, the 1910 Washington referendum was a victory only for some women. Suffrage was still limited to those who could read and write English, and restrictive citizenship laws blocked Native American and immigrant Asian women from voting. It would take 64 more years of struggle before the English literacy requirement was finally expunged from the state constitution. Mary and Emily did not live to see it, but their daughters’ daughters did.