In short order, it became clear that what Marnie had was more than the cold she was expecting, as her conditions turned south toward a more flu-like illness. She started to experience chills, her temperature climbed and her energy was draining away.

In the days that followed those first symptoms, the 67-year-old retired nurse and attorney did not improve and, in fact, continued to feel even worse. She was waking up in the middle of the night drenched in sweat. She lost her appetite, was having diarrhea and couldn’t stay hydrated.

The fatigue was unlike anything she had experienced; her feet felt like they were cast in concrete. In the morning, she had to lie on the couch just to recuperate from the effort of using the bathroom. Even the idea of brushing her teeth was too much. Tom and Marnie’s nightly Scrabble games halted.

Tom, 71 and a retired physician, still felt healthy. He may have noticed some sniffles or a slight cough, but it was allergy season and he paid it little mind.

No one had yet died of the new global virus that had just arrived in Washington state — at least no death had been announced. Its spread through the Puget Sound counties was widely believed to be minimal. No one had been diagnosed in Kitsap County, where the couple live, and they had not traveled to any affected regions.

MORE ABOUT THE SPREAD OF CORONAVIRUS: Coronavirus has jail lawyers worried about safety — for clients and themselves

And so, as Tom monitored his wife, he continued with his daily routine — riding his bike with friends, buying coffee, even volunteering to drive an older man to the grocery store. The vet stopped by to examine the dog; someone came to fix the phone.

Marnie’s conditions, on the other hand, continued to worsen. Her fever was over 100, her body ached, she still couldn’t move or eat, and she was coughing deeply. By that weekend, on Feb. 29, the same day officials announced the first confirmed U.S. death from the novel coronavirus, Tom began to wonder if this was no normal flu.

So, on March 1, he reached out to an old colleague at Virginia Mason Medical Center. “I raised the question of, ‘Is there a way to get her tested for COVID-19?’ ” he said. The answer: Because of strict federal guidelines, only if she was admitted with pneumonia.

Tom, meanwhile, still felt healthy.

By March 2, Marnie’s condition declined further. Tom listened to her lungs and heard a crackling sound, an alarm bell to the veteran doctor. He was getting worried and less comfortable with serving as his wife’s medical provider. That day, they took their first trip to the emergency room.

When they arrived, “the first thing they told us is you can't be tested for COVID-19,” said Tom. Marnie had not traveled to China or a region considered affected and the strict Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines remained intact. Instead, they gave her intravenous fluids and sent them both home.

The fluids briefly helped, but Marnie began to decline again. Her fever hit 102.4 this time. Both she and Tom were becoming even more suspicious she had COVID-19.

Tom still had no symptoms.

As their concern rose, the Bainbridge Island couple continued to receive the same message from medical providers: Neither had traveled to affected regions or interacted with known cases, and Marnie did not have pneumonia, so they could not get tested.

By Friday, March 6, Marnie’s personal doctor urged them to return to the emergency room anyway. Marnie was starting to have abdominal pain and none of her past symptoms were subsiding. She was so tired she didn’t want to leave their home. But Tom “scraped” her off the couch and took her to the city.

At the ER, she received a CAT scan, which showed lung damage. And so nearly two weeks after her first symptoms, Marnie was tested for COVID-19. Doctors sent the sample to the University of Washington’s laboratory and the next morning the results returned: positive.

Nothing had changed with Tom’s health. What he believed were his allergies still lingered, but in his professional evaluation, he was essentially asymptomatic. But because his wife was positive, doctors tested him as well. The next day his results returned: He too was positive for COVID-19.

Tom and Marnie Malpass became cases number 1 and 2 in Kitsap County.

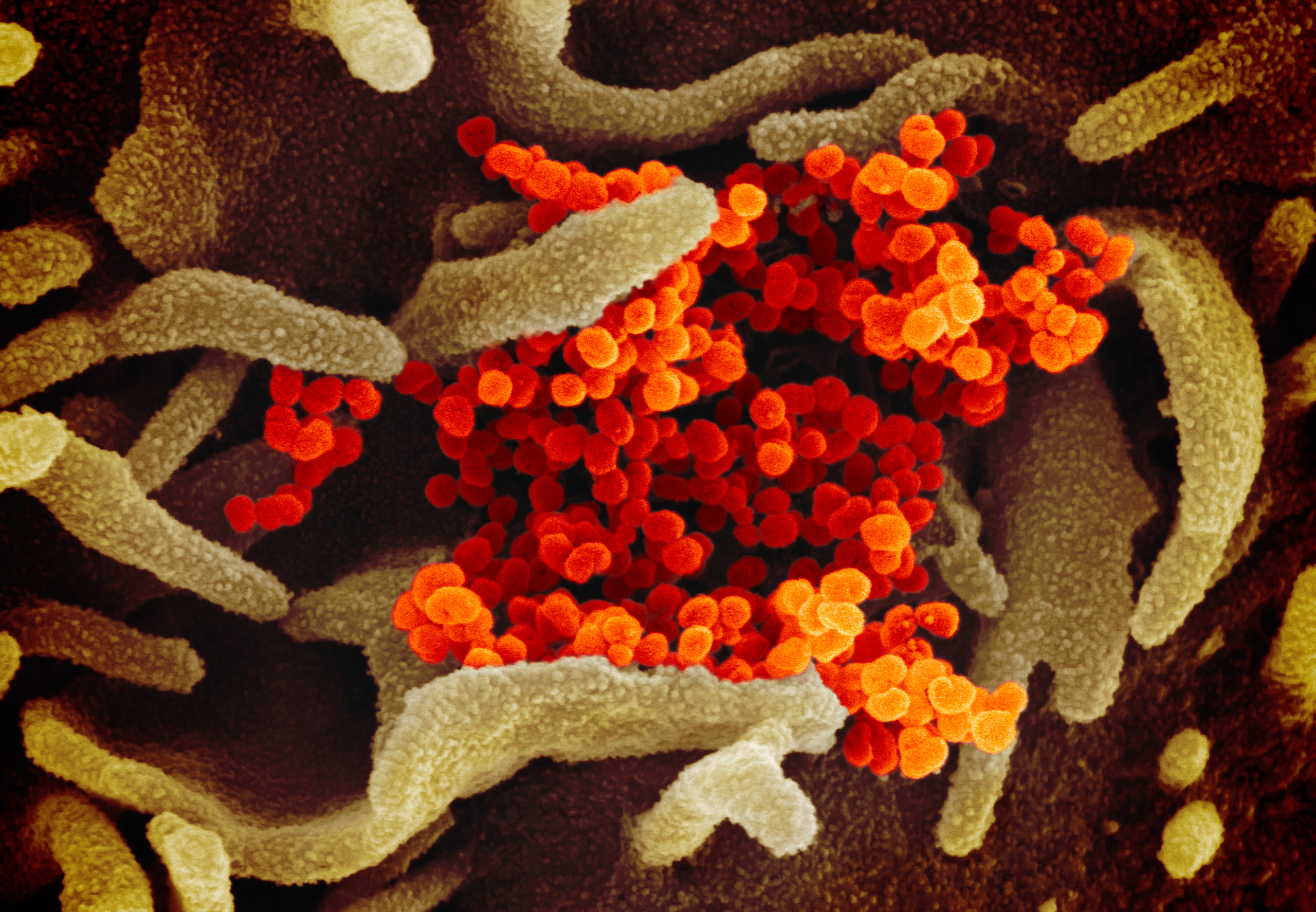

The novel coronavirus is not as deadly as its cousins, SARS or MERS. But its symptoms range from deadly to nonexistent, infecting the majority of its hosts only mildly and allowing unaware people to continue to move about their days infecting others. The twin challenges of identification and containment have led to the incredible measures currently underway in Washington state and across the globe.

A recent study of the spread of the virus in Wuhan, China, where it originated, pegged the majority of blame on “stealth transmission” by those who are contagious but not showing symptoms.

By the study’s estimates, for every confirmed case early in the epidemic, six people were likely infected but not showing signs.

Now positive, the Malpasses retraced their steps from the weeks before. Where had they caught it? At a theater performance in Seattle the week before? Or had Tom, despite showing no symptoms, been the one to infect Marnie? He had recently volunteered at Seattle-King County’s massive temporary clinic for the poor and homeless in Seattle Center. Did he bring it home from there?

At the same time, they thought of the people whose paths they had crossed and worried for their safety as well. They thought of the vet who came to see their dog and the telephone repair man. Tom thought of his bike rides and the coffee stops and the man he drove to the grocery store. That anxiety — and nagging guilt — has gripped millions worldwide, as understanding of the coronavirus and the appropriate caution toward it is crafted slowly and clumsily.

After their positive tests, the Malpasses were moved to a negative pressure isolation room — a tuberculosis-level precaution now reserved for the most serious coronavirus patients — where they stayed for five days. They were transferred so quickly, Tom was unable to move his car, which he had parked on the street, only to receive a ticket.

The whole time the couple watched as medical procedures within the hospital changed by the hour — around isolation, personal protective equipment, testing — a confusing dash to keep up with CDC recommendations.

Tom continued to feel healthy — even healthier, in fact, because the filtered air of isolation eliminated actual allergy symptoms. Marnie, though, was still sick. Doctors put her on oxygen to boost her blood levels. And for a moment they considered giving her an experimental retroviral drug.

But by March 10, after 17 days of elevated fever and crushing fatigue, Marnie started to improve. On March 11, they were cleared to go home again and she was given portable oxygen.

The Malpasses met in a Wenatchee hospital, where they both worked in 1986. Before they retired, Tom was a hematology/oncology doctor, and Marnie was a nurse-turned-medical-malpractice defense lawyer.

Their history means they know the world of medicine, of hygiene, of proper etiquette and steps people who feel ill ought to take. But even for them, the uncertainty of COVID-19 was overwhelming, a feeling that still lingers as they mull whether they made the best decisions for themselves and their community.

As they look toward next steps and emerging from their home quarantine, they see even more uncertainty. With supplies being limited, they’re unlikely to receive a test to confirm they’re negative. They’ll quarantine for two weeks, but is that enough? When did the clock start ticking? And what about those reports of people contagious for a month?

“There ought to be a way to check to see if I'm shedding [the virus],” Marnie said over video chat, an oxygen tube hanging from her nose. “I don't feel comfortable being in the community at all. How long do we isolate? I mean, we don't want to hurt anybody. We feel guilty already. We feel that we don't want anybody to be hurt by us. I'm really nervous about that. I’d feel a lot better if I could be tested.”