Around the same time Ostoja-Kotkowski was developing his “chromasonic” sound-and-image productions, physicist Elsa Garmire was wowing students at the California Institute of Technology with her own argon laser shows. The latter caught the attention of Los Angeles filmmaker Ivan Dryer, who went on to found Laserium Cosmic Laser Shows — a program of laser effects set to music that could be used in planetariums.

Enter the Laser Dome.

The planetarium at Pacific Science Center started out as the Spacearium, one of the many futuristic exhibits developed for the 1962 World’s Fair. Hoping to cash in on the laser trend, the Spacearium became the Laserium in 1975. At the time, The Seattle Times called it “a promising new form of entertainment, with many artistic possibilities.”

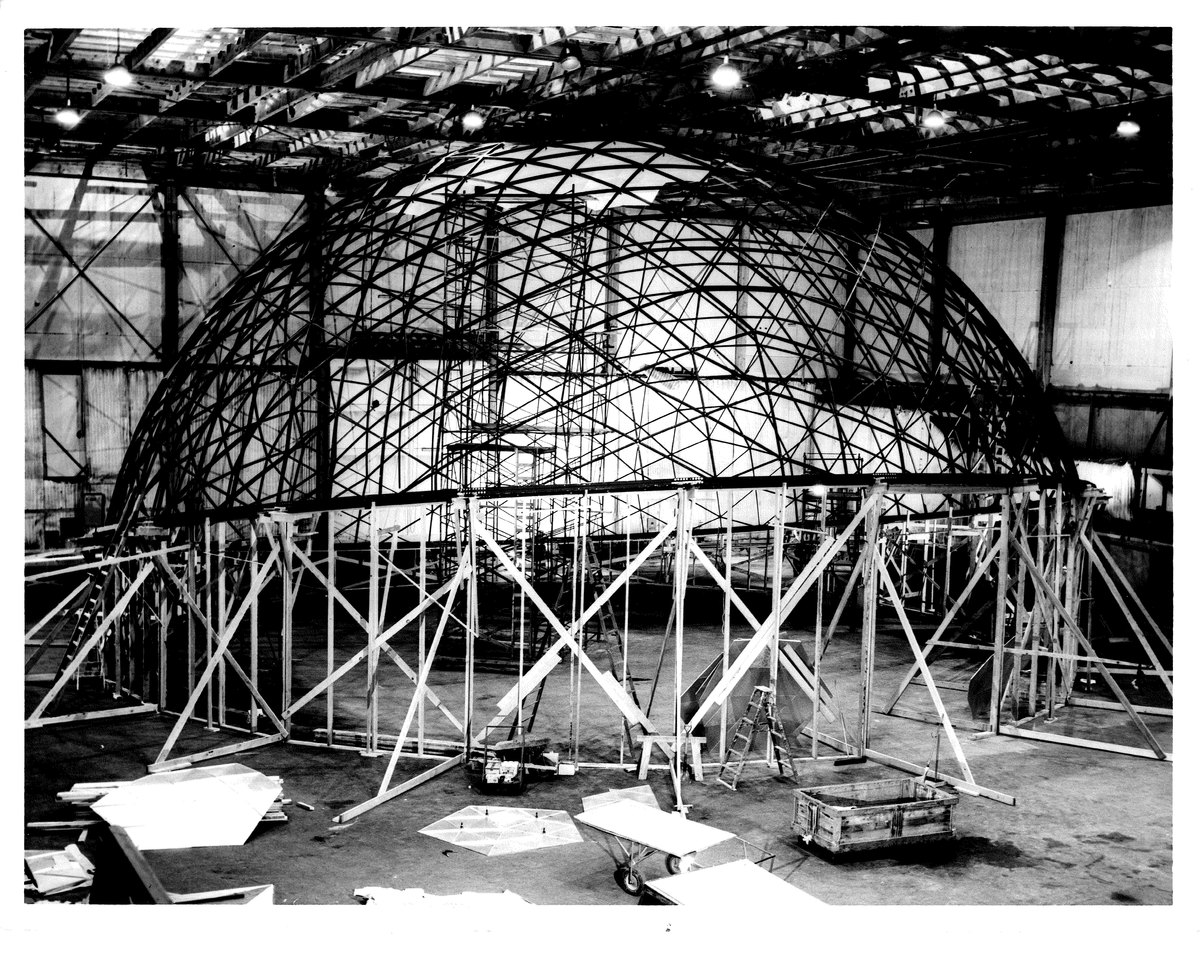

Forty-five years later, the Laser Dome is still delivering on that promise. The 76-foot-diameter dome housed at Seattle Center is the largest facility in the U.S. dedicated to laser shows. It's also the longest running laser dome since the debut of laser shows in the early 1970s.

On a recent night in January, laser artist Jerome Rhett spoke to the gathered audience from the Laser Dome control booth. “Just a reminder this is a live show, so if you see something you like, please feel free to clap, shout or holler."

His voice hushes the circular room full of chatty young people.

“That way it’s not just fun for you, but fun for me as well,” he says.

Above the seats, fuchsia lights bounce off the rounded ceiling. The color fades to a deep red and suddenly, only the curvature of the dome is visible. The mass of people lying on the floor with blankets and pillows disappear in the darkness as an animation of the word “MoTown” emerges from the red void. Like DJs, laser artists have personas, and this is Rhett’s.

On this night, Rhett is performing Laser Lizzo, an hourlong show that includes the songs “There’s Boys,” “Coconut Oil” and fan favorite “Tempo.” During the song “Good As Hell,” he programs a laser beam to stretch out into a line, creating a single flat plane across the dome. When the chorus responds to Lizzo’s “baby how you feelin’?” with “feeling good as hell,” the plane vibrates and appears to match the sound waves from the choir voices. All the while single beams of various colors shoot across the dome from all angles, picking up different beats and melodies.

While laser shows elsewhere are automated, the Pacific Science Center is among the few places in the nation that still employs artists, some full-time, to create new shows from scratch and perform live sets to music. It’s a tradition, and it works; more than 100,000 people visited the dome in 2019.

Rhett is one of six artists that Seattle’s Laser Dome employs. The 24-year-old majored in film studies and graduated from the Art Institute of Seattle in 2017. He started at Pacific Science Center as an Imax theater usher in 2015 and became a laser artist last year.

“I didn’t even know what a laser show was before I started working at the Pacific Science Center,” Rhett says. But now he has his own style. “Color is my big thing,” he says, though he adds that he’s seen other performers create interesting effects with minimal colors.

He believes that if the music is wilding out, why shouldn’t the lasers? “It’s supposed to be a guitar solo, it should be super insane and crazy,” he says. “Have lasers go crazy, blink really fast or have a lot of flashing colors.”

Katrina Marro is the newest member (and only woman) on the laser artist team, and has studied the variations in her colleagues' styles for the past nine months. The 21-year-old says lasers have become her favorite topic of conversation.

“I’m still so new that my style is developing,” Marro says. “I haven't even programmed my own show because programming and performing are two different things. I get a lot of inspiration from my coworkers, who are all incredibly talented.”

Before she took the laser artist job, the only laser show she had seen was “Laser Daft Punk” at Bumbershoot in 2017. Coincidentally, her first performance would be “Laser Daft Punk” at Bumbershoot 2019. In that instance, she used a previously programmed set, but she can’t wait to begin making her own sets with everything she’s observed.

“Some [laserists] use a whole lot of basic shapes and some like to use more abstract shapes, or it can all come down to the colors,” she says. “All aspects can be influenced by the laser artists’ style.”

Laser artists are positioned in the back of the Laser Dome, in a DJ-style booth. They control everything by using three synth touch pads to change the lasers, animations and tempo. The entire show is visible on a timeline on the artists' computer screen through a high-tech program called Beyond.

But one compartment inside the booth holds a relic of the past: VHS tapes.

“All of the programmed data for the lasers was stored in those tapes. That concept is wild to me,” says Rob Carillo, a senior laser artist at Pacific Science Center who goes by Lazar Wolf when he performs.

“Gas-powered lasers, laser data on cassettes and only three colors,” Carillo says of the previous system. “What a time to be alive.”

In 2016, the laser dome got an upgrade. The analog one-watt krypton gas laser system — which cost $100,000 in the ‘70s — was replaced by a digital system with 10 modern laser projectors.

Around the same time, the team experienced almost a complete turnover, with much younger artists taking the reins. Carillo, who arrived shortly after the new system was installed, notes that aside from Laser Ziggy, the head laser artist, the rest are in their 20s, with the youngest being Marro.

Some of the classic laser shows, set to the music of Pink Floyd, The Beatles and Led Zeppelin, have been running at the dome since the 1980s — a couple of decades before the new staff members were born.

Out of respect for the original shows, and for the repeat customers who remember them fondly, laser artists don’t alter such long-running shows as "Laser Floyd," with its animations of marching soldiers and faceless children falling into meat grinders, a nod to the 1982 musical film The Wall.

Carillo does, however, improvise during guitar solos, like the one in “Another Brick in the Wall.” He uses a multicolored cometlike effect that draws your gaze to one corner of the dome (if a dome has corners), where a rainbow tail hypnotizes as it sways to the solo.

With the new blood came a thirst for new shows. “We were all in agreement that the catalogue was played out, with pretty much the same stuff,” Carillo says. “There were huge gaps in popular music that we could be doing to get new and all kinds of different people to come check out the shows.”

Adding shows with contemporary music gives laser artists something fresh to be creative with and gives younger audiences something new to look forward to, including “Laser Lizzo,” “Laser MGMT” and “Laser Ariana Grande.”

“Laser Kendrick” (as in Lamar) debuted in 2017. “It was a midnight show,” Rhett recalls. “Getting people to come to a midnight show is rough because it’s so late, and there's no guarantee people are going to be like, ‘Oh man, you know what I want to see tonight at midnight? This laser show,’ ” he jokes.

But over the first two months, every “Laser Kendrick” show nearly sold out. “It was crazy,” Rhett says.

Now the team debuts new shows every month.

In January, the Laser Dome premiered “Laser Elton John.” Next month a show featuring recent Grammy sweeper Billie Eilish will debut, and a Mac Miller show is also in the works. (The Pacific Science Center pays licensing fees in order to use music for public laser show performances.) For every new show, the team works together to produce an hourlong set by divvying up the songs among each other, so they all get a chance to interpret that particular artist’s music.

Always looking toward the future, the Laser Dome is innovating in other ways. In December, the team began its “Artists’ Choice” series, in which laser artists work on passion projects, creating a show with the music from an artist of their own choosing. So far, artists have chosen music by The White Stripes, Frank Ocean and Justice.

The Laser Dome also occasionally collaborates with musicians. That means a show will have two layers of live performance: the musicians and the laser artists. In the past, laser artists have performed alongside local musicians such as rapper Campana, and bands including The Hoot Hoots, So Pitted and Fungal Abyss. Next month, the laser artists will perform with New York musicians Combo Chimbita and Portland band Y La Bamba, creating live light shows as the bands play in the dome.

And sometimes innovation means incorporating older forms of musical entertainment.

For the past three years, Carillo has programmed and performed events featuring music by the Seattle Opera. On Saturday (Feb. 1), the dome will host “Laser Opera,” ahead of the West Coast debut of Charlie Parker’s Yardbird at Seattle Opera.

Carillo is planning an hourlong show set to recorded music provided by the Seattle Opera, including original scores recorded during a 2015 opera performance, jazz compositions by the Yardbird himself and music from some of Parker’s inspirations, such as Stravinsky.

And while guitar solos are one thing, opera music presents a different sort of challenge for the laser artists.

“It’s always really difficult to approach, it’s not like the other laser shows,” Carillo says. “It's not like working with modern produced quantized beats. It’s abstract and asymmetrical.”

But Carillo says the shows are always well attended, with “way more people than I would expect to go to a ‘Laser Opera.’ ”

Ostoja-Kotkowski, trailblazer of laser operas, wouldn’t be surprised.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.