I remember the moment as if it happened yesterday. We were in the hallways of what was then the Delta Center in Salt Lake City. Bryant and I approached each other, arms cocked for a shake and hug. Then I felt a big hand on my shoulder, pulling me back.

“Wait, that’s my guy,” Bryant said, breaking from his escorts.

As a burly security guard slammed me into a wall, Bryant was whisked away, like a politician rescued from an assassin. He called back, “Come talk to me.”

I did, but by then I had decided I was done with the NBA. Writing about its players had become tantamount to covering the Beatles, and I didn’t like it. I had started with the league before David Stern and Michael Jordan, and I was happy to be one of the few in on an intimate cult classic.

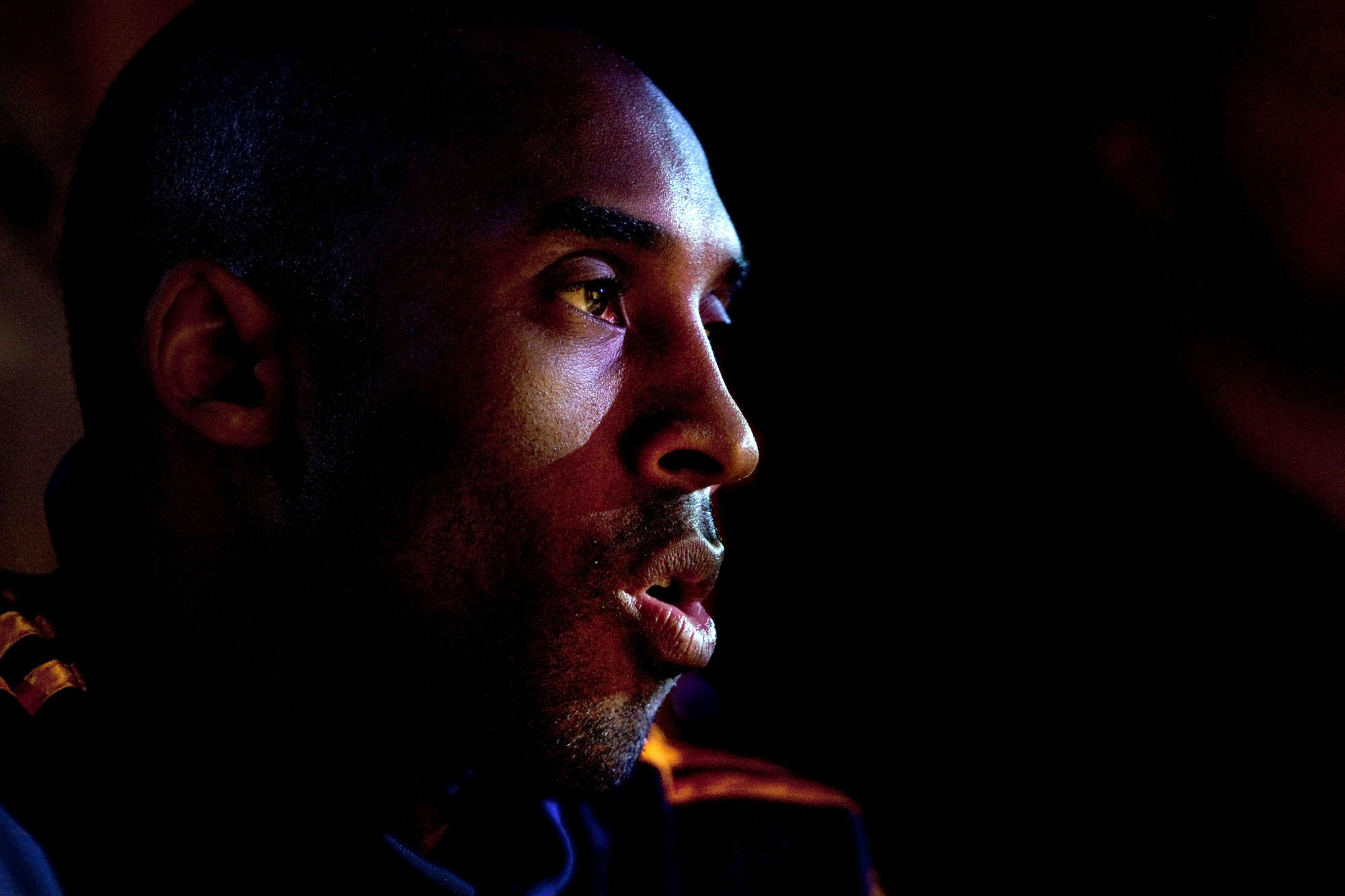

That scene in Salt Lake was the first thing I remembered after the shock started wearing off from the news of Bryant’s death, along with his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, in a helicopter crash on Sunday. (Seven others also died.) Trying to make sense of such a senseless loss, it was obvious, from the grieving masses in downtown Los Angeles to the parade of weeping basketball superstars, that I was not alone. We lose famous and important people every day, but Bryant’s passing landed, almost universally, as few do. He had won five NBA titles and an Oscar, invested in tech and storytelling, spoke four languages and coached girls basketball. He was an extraordinary version of the smartest and coolest person most of us knew.

We have a complicated relationship with athletes and other celebrities. We worship them as cultural deities, yet allow ourselves to believe we’re closer to them than we ever are. We also receive their tweets and proclamations, and infer intention. There’s a subtle racist tinge to it all — we buy their gear (or tickets to watch them) and believe we own them, at least in part.

But we don’t know them, not the way we actually knew Kobe Bryant, a dynamo who was so present among us. He wanted so desperately to be like Mike, but missed the mark, at least in terms of personality. Jordan had an aloofness — cold Air to Bryant’s hot. I spent a week with Jordan, early in his career, and once had a moment — talking about our daughters, alone in the Chicago Bulls locker room; he signed a poster to my oldest, Sassia — but I never really knew him, not the way I got to know Bryant, as fleeting as it was.

I first fell under Bryant’s spell in 1998, while writing an occasional series about Air Apparents during what was supposed to be Jordan’s last NBA season (he returned after two seasons to play for the Washington Wizards). Bryant was 19, going on 35. Just two years out of high school, he was so learned, curious and quick-witted. When I told him I played hoops in his signature Nikes, he asked me how I liked them. I said whatever plastic was used in the shoe made them smell so bad, I stored them in my garage.

Without skipping a beat, Bryant asked, “You ever try changing your socks?”

We slapped hands and popped fingers, but he had me at, “How do you like them?”

Thinking I might be Latinx, the multilingual Bryant once dropped some Spanish on me. When I told him I was Japanese, he said, “konnichi wa,” like a native. I told him I’d be more impressed if he didn’t misspeak his first name. It was derived from the beef of Japanese cows massaged with sake and is pronounced “Ko-beh.”

“That’s because I’m not a piece of meat,” he explained with that V-shaped smile of his.

Bryant later told me that he’d purchased his first home, in Pacific Palisades, an upscale neighborhood between the Pacific Ocean and Santa Monica Mountains. Explaining that I’d been to Gary Payton’s palatial estate in Blackhawk, outside Oakland, I asked Bryant if I could see his. He demurred, then relented, making me swear to never disclose his address or write about the place. I agreed.

His Mediterranean-style abode was something out of the Beverly Hillbillies, complete with tennis court and cee-ment pond (aka, swimming pool). “Is it too much?” Bryant, then 20, asked, with utmost sincerity.

I found those moments more remarkable than Bryant’s otherworldly athleticism or his good-as-Laker-gold fadeaway jump shot. They convinced me that there were prodigies in this world, people who didn’t just have potential for greatness, but were destined for it. I saw it years later in the prep-hoops-playing Ogwumike sisters, just outside of Houston. Like Bryant, they were sharp, engaging and driven. I addressed the younger one, Chiney, as “Madame President,” and now she’s a Stanford graduate, a Los Angeles Spark, and full-time basketball analyst at ESPN. Her older sister, Nneka, also is a Stanford grad, LA Spark and, as president of the players union, helped negotiate the WNBA’s historic collective-bargaining agreement.

Bryant, you just knew, was going to bring the house down. He was going to out-work and out-analyze everybody. He was open with his ambition. He was out there with his life, in a way few larger-than-life personalities are. He was not, however, infallible. He was accused of sexually assaulting a 19-year-old woman at a Colorado resort in 2003. The case was unresolved because the woman was unwilling to testify. Bryant maintained that he was wrongly accused, that he believed the encounter to be consensual, and had to admit to committing adultery against his wife Vanessa.

For a long while, I found the incident difficult to reconcile with the young man I’d known, as well as the grown man he’d become. It seemed to harden Bryant, and eventually led to the much ballyhooed “Mamba mentality,” particularly on the basketball court. He was more calculated and cutthroat. But he later softened. He doted on his daughters in public, became an ambassador for the women’s game, college and professional. Years before, he had recalled that I had daughters of my own and asked what it was like to be away from them so much, in the pursuit of basketball. It was bittersweet agony, I’d told him. He liked that answer, which, then and now, made me feel true proximity to the most human brand of greatness — accessible and imperfect — I’d ever witnessed.