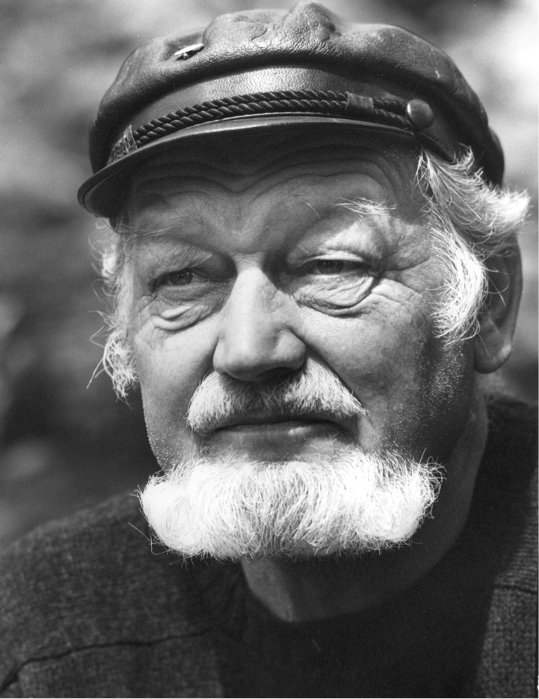

Paul, now 81, meets me at the door. We descend to the basement, a dim, crowded space stacked high with files and books, papers and photographs. Paul points to a large sewer pipe painted in broad stripes of black and white. It is, he says, the Universal Worm — but more on that later. We wind around past his old darkroom, now home to more stacks. Stepping gingerly so as not to trip, we find Paul’s desk, where we sit and talk.

Paul’s signature project, the “Now and Then” column that has appeared in The Times’ Sunday magazine more or less weekly since 1982, grew into over 1,800 variations on a simple theme: Begin with a long-ago photograph revealing a moment in Seattle’s past, ranging from the earth-shattering (sometimes literally) to the mundane (say, hams). Pair it with a current image that approximates the same view, and pen a story that tells the reader what she’s looking at. (More recent “now” photos were shot by Paul’s collaborator Jean Sherrard, who is continuing the column.) Through this method, Seattle’s transformation from frontier settlement to booming metropolis explodes into conveniently digestible bits.

Of course, Seattle has changed profoundly since the project itself began. Reading the early columns today, one hardly recognizes many of the “now” images. With the wheel of history seeming to revolve ever faster, what do we gain by looking back? So many of us are recent transplants; our childhood memories and family histories reside elsewhere. Why should the person who arrived in Seattle just last year, who maybe writes code for Amazon or Expedia and lives in a brand new apartment in South Lake Union, care about the city’s past?

“When you learn stuff about where you’re living, the ground you’re standing on and walk across, you learn its history, you give it depth,” says Paul. “It starts to resound for you and shake for you, and you’re really encouraged by that to pay attention. I think it’s very good for you to study the history of where you live.”

Paul is an excellent storyteller, a quality he traces to his father, Theodore Dorpat. “My dad was so good at [telling stories],” he says. “He was a Lutheran minister; he was actually kind of the bishop of the Inland Empire. And he had a beautiful voice and he was really great in the pulpit. He didn’t have much to say, but he was a great actor.... He was real entertainment.”

Lucky for all of us, Seattle’s history has given Paul a lot to say. But he’s entertaining, too, with an eye for the humorous and the offbeat. Flipping through Paul’s volume on the Seattle waterfront, I happened on a paragraph about Rudi Becker. Rudi was a waterfront character who worked, at pursuits many and varied, near Acres of Clams, the flagship restaurant of Seattle folk musician and restaurateur (and much else) Ivar Haglund. Ivar paid Rudi a monthly rent to hang his “heroic portrait” in the lobby. As Paul explains, “Rudi was this manly hunk of a guy,” and Ivar liked the idea that visitors thought the person depicted was him. When Ivar closed his aquarium on Pier 54 in 1956, Rudi responded with a public scolding: “Seattle’s Only Public Aquarium,” housed in a mason jar. I ask Paul if he recalls other stories of Rudi. He tells me about the time Rudi built a curve into his brick chimney to accommodate a bird nest that was in the way, and relates a story told by Ivar shortly after Rudi died in 1976, which Paul later emailed to me in Ivar’s words:

“One time [Rudi] was down here on my dock talking to a visiting professor from New England, or someplace. They were standing at the rail, looking at the water and the sky on a clear summer night. They were talking about the solar system. When I closed up at about twelve-thirty, I left them standing there, looking up at the stars, gesturing, talking and arguing. I came back early that morning about six o’clock and they were still there! Rudi and this scientist, talking about the sea, the sky and the solar system, on a beautiful morning with the sun shining over the water. That was Rudi Becker.”

I ask Paul whether he thinks Seattle’s history contains more than its share of the weird, compared with other cities. He doubts it: “I think there’s eccentrics in every urban culture. Some of them are wild and wonderful, and [Rudi] was certainly one of our best. And so was Ivar, although Ivar was also a very talented huckster. He was good at making money.” Over the years Paul has collected an enormous quantity of biographical material on Ivar Haglund and, now, freed of other writerly obligations, hopes to work this material up and publish it.

But Paul Dorpat hasn’t merely chronicled Seattle’s weirdness; he also added to it. Dropping pianos from helicopters? Check. Holding a multiday outdoor rock festival, pre-Woodstock? Check. Running a Free University (a concept pioneered by the New Left group Students for a Democratic Society) that spawned an “underground” paper? Naturally. Paul was a key figure in the genesis and production of the Helix, which for three years delivered a weekly or biweekly infusion of lefty politics, trippy graphics and all-around chaotic exuberance to its 15,000 or so readers. And that brings us back to the Universal Worm, which sometimes crawled through the tabloid’s art-laden pages.

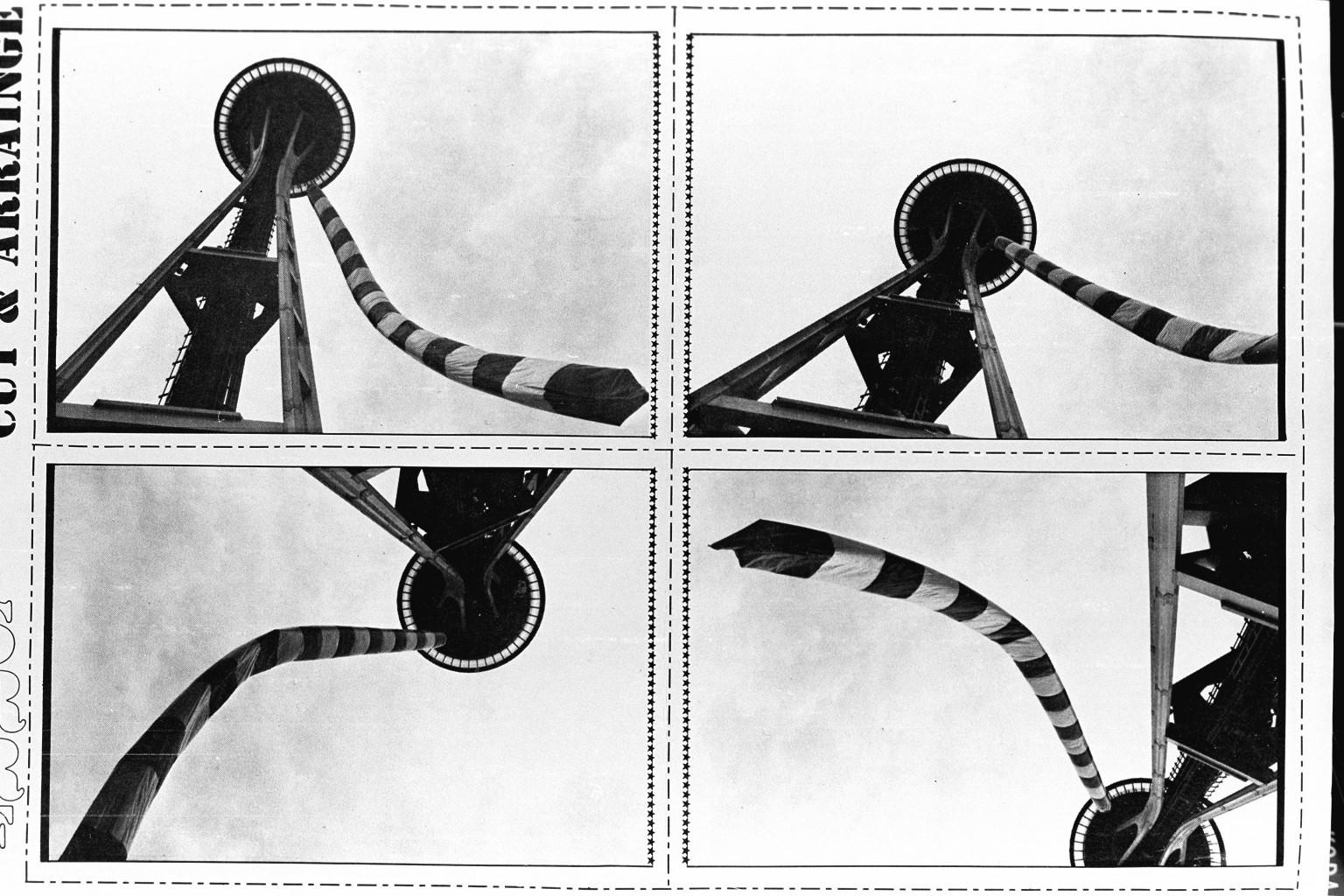

The Universal Worm’s most prominent adventure involved dangling from the Space Needle, incarnated as a 230-foot soft inflatable tube. But what was it? Says Paul, “It was a motif that appeared in paintings [and other art] largely in, I think you could go back to the ’60s and into the ’70s. It’s just a worm with alternate sections, usually black and white, sometimes yellow and black.” OK, but what does it mean? It took some work to get a satisfactory answer out of Paul. Finally: No, no grand symbolism. It was a sort of parody of the more self-serious artists and critics of the day, “an iconic joke.”

All of this was Seattle’s version of the 1960s counterculture: a heady fusion of youth rebellion, artistic and personal experimentation, political radicalism and opposition to the war in Vietnam. It was quite a time to be new to the city: “That for me was an important introduction to a new life, having come from graduate school studying the humanities, mostly philosophy,” he says. “I then suddenly was involved in a communal life of hippies and strange dress and a great deal of fun. And of course intoxication, but not of beer so much, but of psychedelics, and enjoyed it all.”

Recalling my own early days in Seattle, I can’t help feeling a little bit envious. There was, when Paul arrived, the possibility for public life and politics to be creative and playful, as well as serious. It feels like that’s gone in today’s Seattle, maybe in today’s world. We’re all so busy: making money, hustling to keep our heads above the water, grappling with the big social problems. It all feels kind of severe. I try to convey this contrast to Paul. It takes a few tries. Finally: “You don’t have any Dada going around?” No, I say — allowing that maybe I’m just not in the right circles, though I don’t think that’s it. “Well I don’t know,” Paul says. “I’m not in any circle. I’m in the basement.”

I look around. For now, we’re both in the basement. And if we’re all a little bit in the basement these days, I say to my fellow progressives and radicals, take heart: The relative dourness of today’s movements will be redeemed if we can actually start turning the tide.

But back to the past. I ask Paul if he has recommendations for readers who want to dig into Seattle’s history — in addition to his own work, of course. There’s so much more out there now than when he started out, he says: “There’s really a lot of beautiful writing going on, a lot of really talented writers.” David Buerge’s books on Chief Seattle and the Duwamish Tribe earn high praise. He mentions The Tragedy of Leschi, an account by the pioneer Ezra Meeker of the Nisqually chief who was executed, or assassinated, following a disputed court conviction during the Yakima Wars. And, if you’ve never read it, there’s Murray Morgan’s Seattle classic, Skid Road. Of Morgan, Paul says, “He was a brilliant storyteller, and a great person to go to his table and enjoy the conversation. That was a thrill. So I would say that was very important for me, for my cultivation as a regional historian, to have his friendship.”

In addition to continuing his biographical work on Ivar Haglund, and making sure the materials in the stacks that surround us find good homes at the Seattle Public Library and the University of Washington, Paul Dorpat plans to resume a long-neglected passion: painting. He’ll start by recreating the last work he completed in the mid-1960s. It has since been lost, but he points to a photograph that hangs above my head:

“I have a picture of it sort of, see. That’s my first painting, I think. Get the demon out of me: The last painting goes to the first painting, half a century later.”